Online retail businesses thought they might get a chance to relax after 2020. Clean up the mess created by an unforeseen online shopping onslaught. Get on top of things. Take a breath and get strategic.

Instead a renewed tidal wave of online shopping hit them.

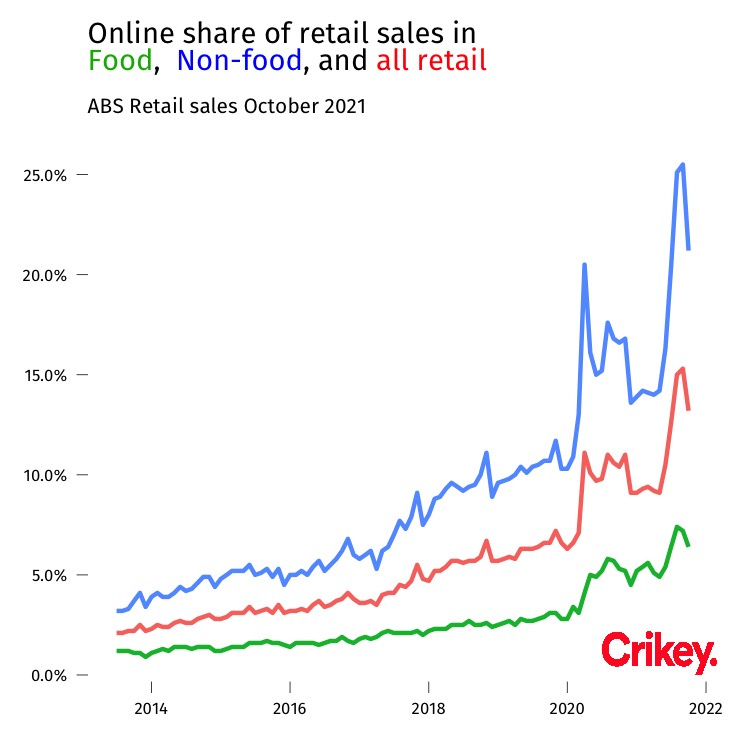

As the next graph shows, Australians’ fervour for online shopping ebbed only very briefly after 2020. After a tiny pause it redoubled and surged to a new high. We are shopping online in ways and volumes never before seen. No wonder the country’s delivery systems are a stressed-out mess.

A graph like the above shouldn’t even be possible.

High growth rates should be possible in small numbers, sure. But high growth rates in large numbers? Rare. It shouldn’t be possible to take a massive industry like everything bought by all Australians and completely transform it in the space of one year and nine months. But that’s what has happened.

Online shopping accounts for well over 10% of all retail, up from just over 5% at the start of 2020.

Big retailers that had limited online presence in 2019 are now deep in the trenches of ecommerce.

Coles has grown online sales 132% in two years. There’s a reason you see those red trucks parked on your street so much more often these days — 9% of all sales are online. Coles sells food and drink so it is part of the green line in the graph above. When you go beyond food, you find even more incredible growth.

JB Hi-Fi did $258 million in online sales in 2019. Now it’s $1.1 billion. A cheeky quadrupling in the space of two years.

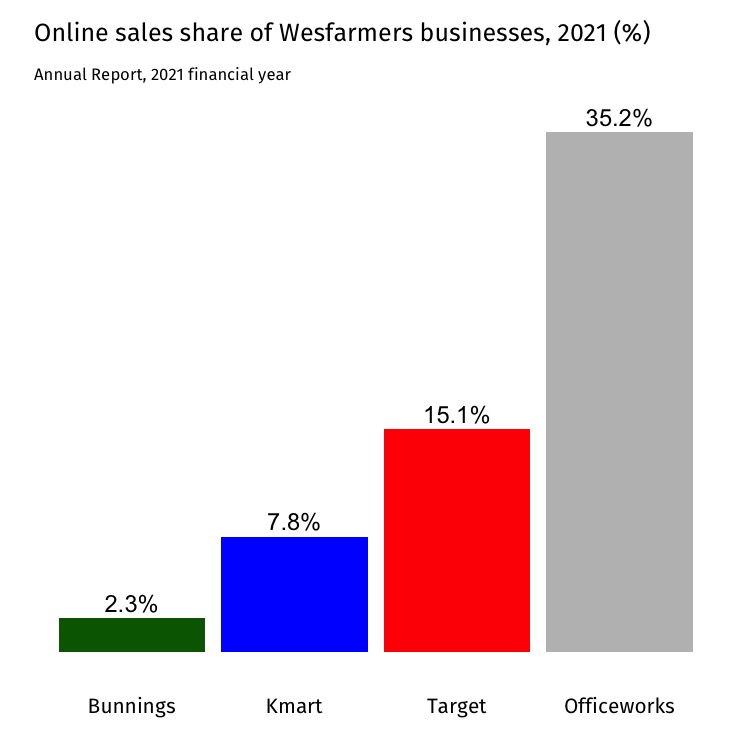

Even Bunnings, which had no online sales platform until recently, is doing serious volumes of sales online. Its share more than doubled from 0.9% in the 2019-20 financial year to 2.3% in 2020-21. That may not look like a big share but it’s 2.3% of $17 billion in sales. And that’s a big number.

Different businesses do different shares of sales online. The portfolio of retail brands owned by Wesfarmers gives us one way to look at this phenomenon, with online share spanning more than an order of magnitude, from 2.3% at Bunnings, to over 35% at Officeworks — as the next graph shows. There are a couple of factors here — the harder things are to deliver, the more likely they are to be bought in person. And likewise for the more measuring and assessment they require before purchase.

As Australia’s familiar brand names have plunged headlong into ecommerce, the fate of online specialists has been worth watching. Amazon and eBay have both done well. Interesting in particular is the case of Kogan. The pandemic shaped up as a boom time for Kogan, with people buying more goods and fewer services. It should have been a time to make great hay. Instead the ASX-listed online retailer has seen its share price plunge after a series of missteps.

Part of Kogan’s trouble has been overstocking and inventory management, but renewed competition from massive trusted brands can’t be helping.

The story that Australia lagged the rest of the world in online shopping penetration used to be true. It is true no more. The US Census Bureau reports that 13% of all retail sales in that country were made online in the most recent period. The data for Australia puts us at 13.2%. Much like our progress with vaccination, we started behind America but overtook it in the end. Now we are among the leaders in the world, and the question is: where to from here?

I can’t wait for some SW developer out there that create an app where independent grocery suppliers out there can collectively sell their goods. Someone I’ve known for many years produces a delicious local brand of Australian chilli salsas, dips and corn chips. Even though he’s won many awards overseas, he still has to pay coles, woolies, etc tens thousands of dollars just to have his products on the shelves. How good would it be for some enterprising company to bring many goods together online and send within couple of days to ones address.

Sounds like that is the future – Down with the Duopoly!

As a child of inner city (Newtown/Sydenham) Sydney in the 50s (when Chester Hill was the west edge, nothing beyond but bushland) I remember the rabbito, the iceman, the baker and the grocer coming street by street in horse drawn carts.

There were few cars and a baby boom happening so it made sense to bring the goods to the customer, providing something that used to be called…I’ll think of it… any minute now…oh, yeah, service.

The concept still exists in Europe on the newer estates ringing the conurbations as in the movie “Meet the Flodders“.

More jobs lost, similar to the self-service situation at major supermarkets.

Many people, women especially, enjoy going shopping. Sitting in front of a computer just doesn’t seem the same.

A Coles delivery guy told me (when recovering from a torn calf) that the most significant clients were mothers because of time constraints, and online precluding unneeded purchases from and crowd control of children.

Interesting article, the important question is has the overall business increased? Or have these gains been made at the cost of their bricks and mortar store sales?

The truth is trying to get advice in a Bunnings store, other than high-end Kitchen renovations, everyone else is too busy stacking shelves.

The question should be asked, pre higher usage of online purchasing, how can high street retail shop front rents be relatively high, when surrounded by vacant shops?

One thing missed with Covid is that many middle aged na dolder possibly strate dusing online shopping and have not returned; enforced innovation and change of habits.

Retail is in transformation, not sure how shopping centres or malls business models will cope, but elsewhere many businesses have reduced their retail rental footprint, invested in networked storage/logistics, upgraded websites and opening up fewer/smaller showrooms/pick up points.