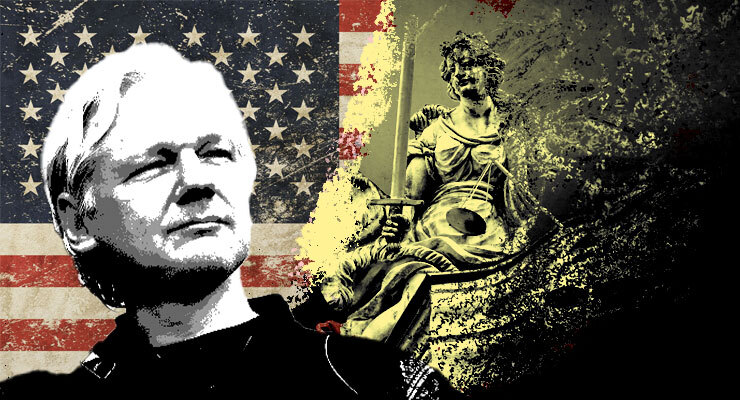

The Julian Assange challenge is creeping closer and closer to home. Despite all the “not my problem” brush-offs by successive prime ministers, it’s all set to turn up — sooner or later — on Australia’s doorstep.

The United States government assured the UK’s High Court that if he’s convicted, Assange would be allowed to serve any sentence in an Australian prison.

It’s great to see British courts eager to uphold tradition: recognising Australia as the jail of choice for political prisoners of the great empire of the moment. But it implicates the Australian government in the pursuit of Assange after all its efforts to waive it off as an American thing.

That 10-year chase by the US government threatens to rewrite journalistic practice in democratic societies for the worse — including in Australia. It’s taking two big whacks out of accountability journalism: restraining how journalists can engage with sources, and limiting what the law will consider “the press” that might be entitled to freedom.

Australian governments have long followed the US in targeting the supply side of confidential information that journalists rely on to challenge governments, persecuting and jailing whistleblowers and leakers. Now, starting under Donald Trump and continuing under Joe Biden, it is targeting the demand side — the journalists who take that confidential information and use it to hold governments to account.

The details of the law turn on the arcania of US constitutional and national security law. But here’s the bad news: the US framework is better for an independent media than the Australian one. Whatever US prosecutors and courts decide, it’s likely to end up worse in Australia.

The core charge is that by receiving and publishing “top secret” information (the cache of US diplomatic cables leaked by Chelsea Manning) Assange breached the US World War I-era Espionage Act. (He’s separately charged for conspiracy under anti-hacking laws for allegedly coaching Manning in how to secretly download the cables.)

It’s not the first time the Espionage Act has been used for things other than, well, spying. Daniel Ellsberg was charged under the act for leaking the Pentagon Papers (the charges were dismissed) and WikiLeaks source Chelsea Manning was convicted (her sentence was commuted to seven years served by Barack Obama).

Earlier presidents had pulled back from using the act against journalists. In 1975 under Gerald Ford, the US decided not to proceed against Seymour Hersh for breaking the My Lai massacre story, and Obama refrained from using it against Assange.

Will Australian authorities approach Australian espionage laws and journalism with the Ford-Obama restraint or the Trump-Biden enthusiasm? Hard to say. National laws were “updated” and expanded in 2018 after an earlier 2002 Howard-era “update”. There is no news reporting defence under the laws.

Australia’s security agencies have indicated they consider document leaks like those of Manning or Edward Snowden to be equivalent to espionage. In 2019, the Australian Federal Police raided the home of journalist Annika Smethurst and the offices of the ABC over other national security breaches that similarly provide no protection for journalists.

The US government under Trump and Biden dismiss press freedom concerns, saying Assange “is no journalist” and the manner in which he solicited information was not journalism. They’ve been encouraged by a bit of old media sneering at the WikiLeaks model. “We regarded Assange throughout as a source, not as a partner or collaborator,” The New York Times editor Bill Keller said in 2011.

Maybe. Whether Assange is a journalist or not, WikiLeaks was certainly doing journalism. That same year, it was awarded the Walkley award for most outstanding contribution to journalism. (Disclosure: I was part of the award panel.)

The Friday night decision by the UK High Court overruled a lower court ruling that although Assange should be extradited, he was too ill given the possibility of the sort of mistreatment endured by Manning. The offer of transportation to the colonies on conviction was part of the “you can trust us” package put together by the US in response.

There’s now a further appeal by Assange, together with a separate appeal against the extradition decision. Then there’s the US trial and appeals, almost certainly to the US Supreme Court.

Seems there’s a long way to go before Australia has to air out a prison cell. Meanwhile, Assange remains in jail in the UK.

Should the Morrison government intervene on Assange’s behalf? Let us know your thoughts by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name if you would like to be considered for publication in Crikey’s Your Say column. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

Should the Morrison government intervene on Assange’s behalf? The answer has to be YES.

Applying the criteria of leaking there are two issues

Truth – John Howard should be in jail for “Children Overboard.”

Official Secrets – Dutton should be in jail but I can’t tell you why.

When Andrew Wilkie and Barnaby Joyce call for the release of Julian Assange he should be released.

When will a whistleblower sink the next crooked Liberal ex PM or senior minister?

OK to Commit a war crime and machine gun innocent noncombatants but 12 years jail and counting for telling the world about the mass murder of the same civilians.

A neat, succinct summary of a disgraceful situation, Eric!

Interesting that revelation of true criminal behaviour is a crime.

It’s not confined to the Benighted States or Blighty – try our 1914 (revised 1961) Crimes Act s70 (i) & (ii).

“you can trust us”

Why?

American assurances haven’t been worth the paper they are scribbled on for the last 400 yrs!

Indeed. The most recent high profile example of the US prison system’s ethos is the suicide of Jeffrey Epstein.

Suicide or ‘suicide’? Epstein was a disgrace and a trial would have been a revelation.

The behind the scenes battle to keep Ms Maxwell alive must be fierce.

Imagine what she might say.

The First Nation people trusted the settlers and were shot . Crooked card players were shot . The ownership of African slaves ended up with both sides shooting each other Throw in a couple of world wars Korea, Vietnam, and a few other skirmishes and there is little evidence of compassion solving problems in the American psyche

With gun deaths in society running at around 50 thousand per year and school massacres at 2 or 3 a month I do not see much chance of Julian Assange being shown compassion.

Thanks for that excellent article Chris. Of course, I agree entirely with the comments that you make and the sentiment that you express.

In fact, only last night I was thinking that Crikey seemed to have been strangely quiet about the plight of Julian Assange, so it was most pleasing to read your piece today.

In the west in general and in countries such as Australia and America in particular, we do enjoy a degree of

‘freedom of the press’ and freedom of speech’, certainly far more so than in countries such as China or Russia, to name but two. However, that freedom only goes so far.

When whistleblowers such as Julian and others who you mention in your article such as Daniel Ellsberg, Seymour Hersh (what an appalling atrocity he exposed!) Chelsea Manning, Edward Snowden and Annika Smethurst, expose really important things, it is they who are pursued and very likely punished.

I am appalled, saddened and angry at the way the Australian government, Her Majesties ‘Opposition’ and the main-stream media have all, by-and-large, ignored Julian’s plight over the years. Successive Australian Governments have been too busy burying their noses between Uncle Sam’s buttocks to notice anything untoward in his behavior toward citizens of this country. These governments are to be condemned for their inaction in this matter and for their treatment of whistleblowers in general.

Your article Chris, again emphasizes the crucial importance of good journalism and the existence of organizations like Crikey in exposing the dark side of our governments and our society.

Thank you very much!

Stalin was very good at silencing whistleblowers. Consider the fate of Welsh journo Gareth Jones. Between 1931 and 1933 he exposed the Ukraine famine. He was kidnapped and murdered in 1935. The Soviet NKVD was suspected of the murder.

Freedom of the Press? Not in the West if you dare to write an article for someone the US disagrees with. https://goodwordnews.com/us-threatens-6-figure-fines-for-contributing-to-banned-sites-reporter-told-rt-rt-usa-news/

As another Pundit stated:

“If Julian Assange were a Chinese journalist and publisher, he’d have the Nobel Prize, be the centrepiece of Human Rights Day, and his portrait would’ve been planted atop President Biden’s Democrazy Summit.

Assange’s name would’ve been the first on US Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s list of 350 journalists under threat, published, without irony, on the day his administration sought to extradite Assange to face 175 years in a supermax prison.

If Chinese crimes rather than American crimes had been revealed by Assange, he would now be the poster boy for the Winter Olympics’ boycott campaign.

Every news bulletin would have led with his fate, every press still turning would be rolling out the outrage at the crushing of this butterfly on the wheel.

Poor Julian, if only he had been born Chinese”

Western hypocrisy much and our brave LNP Government doing what they do best, nothing.

Yep, he’d get the full Liu Xiabo treatment.

Missed the point as usual. He’s getting the Asadullah Haroon Gul treatment on steroids. As usual the moral “West” takes the “do as we say, not as we do approach”. Hear no evil, see no evil and speak no evil if it’s a White Western Democrazy doing the crimes.