For years we have talked about “conservation”. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) runs the crucial Red List of threatened species. People who work for nature call themselves conservationists. I am a trustee of the excellent Zambia NGO Conservation South Luangwa.

But of late people have begun to question the term and everything it implies. If you conserve something you are seeking to look after it, to keep it as it is, to make sure nothing bad happens to it. You conserve a Renaissance painting by keeping it safe from vandals, humidity, direct sunlight, fungi and insects so it stays as lovely as always.

Conservation was the big word at the beginning of the environment movement. Different authorities prefer different dates for its starting point: a favourite is 1962, when Rachel Carson’s revolutionary Silent Spring was published. I prefer 1946, when Peter Scott set up the Wildfowl Trust at Slimbridge, in Gloucestershire, and a few years later established an unprecedented and highly successful initiative to save — or conserve — the nene or Hawaiian goose.

As the movement developed it was, at last, widely accepted that humans had destroyed a great deal of nature, that this was a “bad thing” but with human effort and human will we could conserve what was left. Good idea.

But while this new breed of people called conservationists sought to conserve nature, the opposing forces carried on destroying it.

They did so with infinitely greater financial resources, driven by ever-developing technologies and the demands of an ever-increasing human population.

The forces of destruction have not achieved a victory. It’s more like a rout. Industry, intensive farming, transport and urban sprawl have nibbled and hacked away at nature: a recent BirdLife report found that one in five of all European bird species is threatened with extinction; since 1970 there are 40 million fewer birds in the UK.

The idea of conservation as an essentially passive process is old hat. There have been many calls for a radical new approach and with it, a radical new term. We are no longer trying to hold on to wild places and wild creatures — too many have gone. What we should be doing is bringing them back.

Not conserving but rewilding.

This is a confrontational and polarising term. It is also inexact. It covers many different approaches, from allowing nettles to grow in a corner of your garden to releasing wolves into the wild. It attracts a lunatic fringe, it attracts a more-radical-than-thou youth wing. It also attracts middle-of-the-road people eager to work for nature — the artists formerly known as conservationists.

The idea of rewilding is becoming sexy. It is attracting some serious cash: the EU’s Life program, which funds initiatives for environment and climate, handed out £3m between 2014 and 2020; a major beneficiary is the organisation Rewilding Europe.

This inevitably involves schemes and projects that provoke the heartiest opposition. Humans have been an agricultural species for 12,000 years and over that period have fought and won a war against nature — do we really want to let go of that victory? It’s an atavistic fear, and not one that will be soothed when people talk of releasing wolves.

One definition of rewilding is simple enough: in a given environment, control should be handed back to nature; any environment should, at heart, be self-regulating.

To grasp that notion you need first to understand the succession of vegetation. That city park, that wheat field, that back garden is trying to be an oakwood: leave it to itself and in a thousand years or so that’s what you’ll get. We take control of the succession by weeding, planting, strimming, mowing, using herbicides, pesticides and fungicides. It’s called land management: equally important in a window box, on a golf course or a 1000-acre farm.

So what if we stopped managing?

For years, the answer to that has been sought at Oostvaardersplassen (OVP), sometimes known as the Dutch Serengeti. This is a place that was created in 1968 on marshland near Amsterdam, across 22 square miles. It’s an attempt to recreate the pre-human landscape of these low and soggy lands.

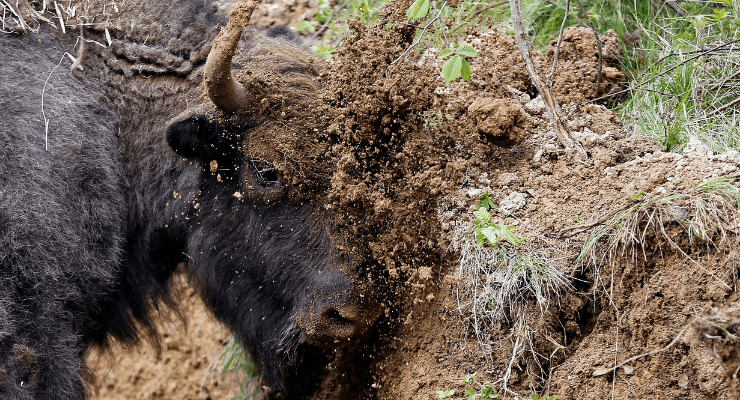

Critical to the vision was the introduction of large grazing mammals: deer, hardy ponies and cattle. The cattle played the part of its extinct ancestor, the aurochs. The project was driven by the idea that the landscape should run itself, just like the rainforest and the African savannah. Cattle and trees would die where they fell and be returned to the economy of the soil, feeding uncountable thousands of invertebrates and fungi. Nature would make the decisions.

“The search for wilderness needs wildness in the mind,” said the Dutch ecologist Frans Vera, who masterminded this project. His book Grazing Ecology and Forest History was translated into English in 2000. Its text is an invitation to change the way we manage land for wildlife.

There are plenty of wildlife reserves in Europe. Many are managed in different ways and for different reasons. Dead and dying trees are often removed from woodlands well-visited by humans for health and safety reasons, and also because dead timber offends the eyes of traditional foresters. If you want heathland birds, you must graze or mow the heath; otherwise it will turn into an oakwood and become unsuitable for Dartford warblers and nightjars.

But now, the idea of management by neglect — the correct term is minimum intervention — has begun to gain traction. Real wildness needs space. Space without humans.

An approach based on that principle has been encouraged at a number of significant sites across continental Europe. In many places, this has been made possible by the abandonment of once-cultivated, now uneconomic, land and the flight to the cities; in other spots by less intensive stock management.

These include areas such as the Greater Coa Valley, in Portugal; the Danube Delta, in Romania; the Southern Carpathians, also in Romania; Velebit, in Croatia; the Central Apennines of Italy, and Bulgaria’s Rhodope mountains.

This process involves a rethink, not only about space and management, but also about large carnivores and large birds of prey.

Until the 1960s, the Spanish government was paying a bounty to people who killed bears and wolves. Since then there has been a change, not just in thinking but in European law: the Bern Convention of 1979 gave legal protection to bears, wolves, lynxes and wolverines. That lack of persecution has allowed these animals to spread. Bears have been reintroduced to Austria, the French Pyrenees and Italy. I managed to get quite close to a bear in Slovakia.

The IUCN runs the Large Carnivore Initiative for Europe. The basis of its manifesto is that large fierce animals have the right to exist, that Europe is the richer for their presence, and that we have a duty not just to conserve, but to encourage them for the sake of future generations. Europe has 17,000 brown bears, 12,000 wolves, 9000 Eurasian lynxes and 1200 wolverines — none of which you will find in the UK.

A few years ago, I visited Alladale, in the Scottish Highlands, a wilderness reserve owned and run by Paul Lister, heir to the MFI fortune. He has given much of his energy to rewilding the estate. Mostly that involves trees.

The hills of Scotland are famously bare, but that’s not their natural state. It’s the work of humans. The trees were cut down to build ships, for construction and for fuel. They stay bare because they are grazed by sheep and deer, which are managed so that rich people can shoot them.

Lister has planted more than 900,000 trees, behind deer-excluding fences, and a transformation is taking place: in a century or so it will be quite something. He has reintroduced red squirrels and is involved in a project for breeding wild cats. The place also operates as a high-end tourist destination, with lavish accommodation.

Lister’s great ambition is to bring back wolves. He is convinced it is feasible: first establish game-fencing, tested and proven in South Africa, then let the wolves get on with it. Opponents claim he is “howlin’ mad”.

Rewilding Britain is keen to bring back the lynx, part of the ancestral fauna (along with wolves and bears). Such a reintroduction could be done in secret and nobody would know: they’re not creatures that flaunt themselves or are likely to cut a swathe through domestic stock.

But opposition is always there to such projects, fuelled by scare stories. A good few species have been reintroduced to the UK, but many such projects have been frustrated.

They have also been branded, by some conservationists, as vanity projects that concentrate on large spectacular animals, when what we need is to improve the environment from top to bottom. But reintroductions have had some spectacular successes: red kites, white-tailed eagles, ospreys, cranes and white storks.

It is more difficult still to get support for the reintroduction of large mammals, but two significant species have come back in recent years. Wild boar have spread out from animals that escaped or were released during the ’80s fad for their meat. There is now a sizeable wild population in the Forest of Dean, in Gloucestershire, and smaller groups elsewhere; there are 2600 wild swine in the country.

Beavers have also made a comeback, one that started with illegal releases in Devon and Scotland. After long discussion and much opposition, it has been decided that they can stay, and other licences for releases are being planned.

These animals change landscapes for the better, enriching the habitat for a suite of different species.

Rewilding implies a change of land use. I knew the reserve at Lakenheath in the Suffolk Fenlands when it was a carrot field. In 1995, the RSPB took it over and turned 400 hectares of intensively worked agricultural land back into fen: a place where you can find cranes, marsh harriers and bitterns.

In the East Midlands, the Great Fen Project covers 14 square miles. It’s an initiative that involves land with several different owners, only some of them wildlife organisations. It’s about joining up wild places, and it’s usually called landscape-scale conservation — rewilding by another name.

These big projects have their problems as well as their opponents. In the Netherlands, OVP has been going through traumatic times, with the grazing mammals in poor condition, many dying of starvation, and a great deal of public anger as a result. The place is enclosed and contains no natural predators of large mammals: in short, it’s only a bit wild. It cannot, in the end, be truly self-regulating.

The rewilding project at Knepp Castle, in West Sussex, has become a model of its kind — unproductive farmland transformed into a wild place of great richness.

I should also mention the land around my house in Norfolk: a few acres of marshland that, thanks to our minimum intervention, supports otters, marsh harriers, barn owls and nine species of breeding warblers.

The idea of rewilding has a deep romantic appeal to many people, just as it provokes atavistic fears. A few years ago, a plan to release white-tailed eagles in Suffolk was stymied by farmers who feared the large birds would carry off their pigs. The opposition was short on biological facts, but very long on scare stories.

But in the end, this is a contrived animosity. True rewilding is about an acceptance that when land is managed for the benefit of non-human species, humans themselves will find something meaningful. It is about connectivity: reconnecting one wild place with another, and reconnecting the human mind with nature.

The first step in such a process is not rewilding the countryside, but in rewilding human minds.

In Australia our biggest hindrance to rewinding is the opposite of European conditions. We don’t need to reintroduce endemic species for them to thrive but need to eradicate introduced ones for our endemic species to thrive. Land management would have to work differently due to the role of fire in our landscape; can’t leave it be like in Europe.

Ridding the marginal inland of hard hoofed Bovis & Ovis would be favourite.

Not to mention the horse plague in the Snowy Mountains.

Again I argue for the introduction of permaculture principles to our early education system. We need to rewire our attitude to nature, realise that our only hope is to embrace our place within it, and stop constructing dead surfaces over the living earth.

I disagree. We can’t feed 7-12 billion people without intensive agriculture. I also think that our conservation problems are to do with the particular actions we take, not the attitude behind them.

It is untrue and morally myopic to state “We can’t feed 7-12 billion people without intensive agriculture.” because it presupposes a meat clogged, ‘western’ diet.

The vast majority of grains (excepting rice) and 70% of the fish catch is fed to livestock to produce milk, eggs & meat.

As the area of a habitat decreases, the pressure on its animal population increases, and increases most with the largest of its species. Fingers crossed, the populations of the large species can one day be topped up by cloning from bottled specimens. The smallest species, including the microbiota, are varied and resistant to periodic crashes, but in their variety they are hard to bottle. Small conservation zones could conserve whole ecologies then, with a continuous inflow of larger animals from zoos worldwide.

A worthy piece but generally of marginal relevance to Australian conservation challenges. Rewilding by bringing in new populations is often a ’boutique’ highly intensive process that can be feasible in say, Britain with 65 million people in an area the size of Victoria, and generally small natural areas with lots of taxpayers and volunteer communities nearby. In Australian parks and conservation reserves that are remote and commonly hundreds of thousands of hectares in size or larger, it’s much less likely to be viable. Here, the demonstrated cost-effective approach is the control or eradication of ‘threats’ – weeds and pest animals like pigs, cats and foxes (which is a prequisite for successful rewilding in any event). That’s followed by broadacre treatments that give native plants and animals the best chance to repopulate eg burning, environmental watering and revegetation. Unfortunately 20 or 30 conservation years were lost in the 1970s, 80s and 90s when many national parks were established with the hope that just removing disturbances like stock grazing, logging and mining through changes in law and policy would allow ecosystems to recover to a natural equilibrium. Then, at least 20 years ago, Australian conservation managers adopted ‘a new approach to conservation’ by realising they had to carry out intensive and continuous work – shooting, baiting, watering, burning, re-seeding. That is, actively managing land for conservation. Now, park managers are moving to the next phase, with climate change interventions such as using non-local plants from warmer drier locations that have a better chance to survive. Next time you see the ‘salt of the earth’ types slamming tough, confronting work like the culling of brumbies in the NSW and Victorian high country then ask, who are the squeamish ones here – the greenie conservationists or the people in the big hats?

Australia’s endangered species are not large, romantic ones like bears or lynxes. Most of ours are unseen, unphotogenic and unmourned when they vanish. It’s also very difficult to see the current Liberal/National Party agreeing to increasing the budget for park management, viewing land management as anything more than building dams or removing woodlands, or even admitting that climate change is a real problem.

The trouble is governments, state and federal, still have a slash and burn mentality…..the “economy trumps the ecology” mindset. Hence Australia is losing habitat at near world leading rates. Have to overcome that mentality in order that the efforts of those who know what’s what can make some difference.

Pesticides and rodenticides, as Birdlife well knows, are two of the biggest killers of birds throughout the world, along with many other species, including bees

I believe Europe introduced a temporary ban on some products deemed harmful to animals (and humans) years ago, but has since been pushed into revoking such.

So many people, fearful of having weeds in their gardens and lawns, run outside on windy days, spraying weedkiller everywhere without a care in the world. Not concerned that it can be carried on the wind.

Personally, I went back to weeding by hand over thirty years ago after losing part of my lung due to potting mix containing bacterial from “third-world countries” according to my surgeon, when test results came back.

From then on, I read labels on everything and still do – making a conscious effort to not cause harm to birds and animals (myself and my family) by using products that manufacturers and governments know full well, cause death (human and animal) and injury.

Trying to convince others, though to do likewise? Like hitting my head against a brick wall.

They may be assured by Potting mix dangers, because at least a dozen human deaths are recorded in Australia each year and hundreds in other countries – but asking people to choose back-breaking hand weeding as opposed to quick and easy spraying -usually done without wearing a mask themselves, thereby totally oblivious (or stupid) to the dangers , is quite something else. After all, they see Council employees doing the exact same thing and probably think …well, they’re doing it, it can’t be that unsafe.

It goes without saying, that birds have no idea when they’re pecking around lawns and flowerbeds trying to find worms and bugs for themselves and their chicks, that the places they’re sticking their long beaks into, are saturated with chemicals

Having witnessed the sad deaths of three female adult magpies that I’d named and who used to visit me several times a day in drought, bushfires, looking for food which I happily supplied – but then after two neighbours hiring gardeners to spray/saturate lawns and gardens beds, the birds somehow thought they’d get more natural nourishment.

Unfortunately, by the time each of the three came back to me, they were distressed, breathing heavily, confused and over the course of twenty four hours, lost the ability to fly. It was heartbreaking to watch. They would not allow me to capture them but went off to hide in inaccessible parts of my garden (deliberately left so for them to hide in with their young, when larger birds came looking for chicks and fledglings to eat) where I sadly found them dead on the following day.

Heartbreaking too because the male Magpie grieved for up to two weeks, his melodious carrolling replaced by the most mournful screams and calls, thatI did not think birds capable of making.

This is without the effect on smaller birds and bees, butterflies and quite possibly even worms.

A friend in Sydney during lockdown had no idea that spraying rodenticide around her home to stop mice and rats, could have killed her two dogs….both of whom were finding dead bodies, picking them up in their teeth and showing off to their owner .

It didn’t matter that I warmed her of the dangers, she just jumped in, because it was an easy solution.

I could go on and on, about things I’ve seen…but in the big scheme of life, everyone just wants the time quickest solutions to make THEIR lived better.

For me it’s heartbreaking and totally avoidable…but it’s only my opinion at the end of the day.

If anyone remembers the (last) mouse plague, the gNats demanded the release and cost free supply of one of the worst poisons which had been previously banned.

Within days, vets all over NSW and a couple of his electorate reported that they were putting down farm dogs several times a week from poisoning, either directly or eating the rodent corpses.

Similarly with Magpies and others up the food chain – because it is a nerve poison the symptoms you describe are highly indicative.

They seem frightened as if on a bad trip, quuckly lose the ability to fly, then cannot even walk and die with tremors wracking their bodies.

It’ll be a very Silent Spring before this is over.

AND they want to do it again, pre-emptively because the wet harvest is going to leave the fields carpetted in loose, rotting grain.

Makes some wish that Omega would get amove on.