“He’s not the Messiah; he’s a very naughty boy,” may be what finally gets inscribed on the tombstone of Julian Assange. History has a habit of serving up tarnished heroes, much as we’d prefer it otherwise.

Like anyone who attains the status of iconic mystery, Assange — not actually seen freely moving in public in a decade — has become less person and more mirror, reflecting the meanings we choose to attach to him and his experiences. What he actually thinks is known only to him, and his lawyers presumably.

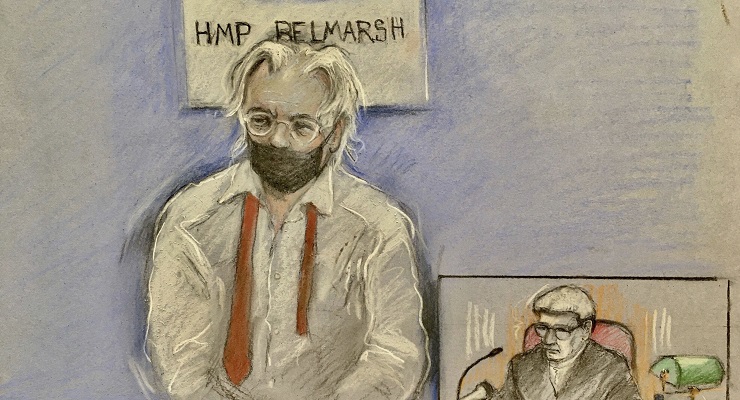

The UK High Court’s decision to reverse a lower judge and affirm that Assange can be extradited to the United States where he faces espionage charges over the 2010 WikiLeaks publication of classified intelligence files, has brought Assange back into the spotlight. He’ll try another appeal, no doubt, but it’s looking bad for him now. A long stint in a US federal prison is very much on the cards.

The Americans have no sense of humour about being embarrassed, which was Assange’s real crime. WikiLeaks pulled their pants down, and each president from Obama to Biden has sworn revenge, happily putting aside the ordinarily sacred First Amendment to pursue Assange on the very controversial basis that he is not a journalist but a spy.

Assange’s own government (that’d be Australia) is maintaining the stance it has always had: Julian who?

We have a fabulous track record for extending consular assistance to our citizens who strike legal troubles overseas, often negotiating their way out and home; rescuing Kylie Moore-Gilbert from Iran, where she had been imprisoned as a spy, is a recent glorious example.

In Assange’s case, however, we have done nothing. Australia, the government said the other day, is “not a party to [Assange’s] case”, a statement of the irrelevantly obvious. Our assistance has been limited to reminding the Brits and Americans of “our expectations of due process”. No prisoner swap one foggy night on London Bridge is in prospect (we could at least offer them Tony Abbott back — he wants to go anyway).

Russia was far more forthright in denouncing Assange’s legal persecution, calling the UK court’s decision “a shameful verdict in a political case against a journalist”.

Hang on. Russia? Bastion of the free press?

Well, there’s one of Assange’s problems. According to a lot of accusers, including the US Senate, WikiLeaks actively cooperated with Russian security services to interfere in the 2016 presidential election. Specifically, it released emails stolen from the Democrats, with the evidence strongly pointing to Russia as the thief.

Related, maybe, is the temporary affection Donald Trump had for Assange’s baby back then: “I love WikiLeaks,” he famously proclaimed during the election campaign, referring to it as a “treasure trove”. Whether Trump was an actual Russian babushka doll or just an unwitting beneficiary of Russian espionage activities, his endorsement is hardly beneficial to Assange’s martyrdom claims.

And then there are the rape charges. Lest we forget, when Assange entered the Ecuadorian embassy in London in 2012, he was facing imminent extradition not to the US but to Sweden. Those charges were never resolved, because he outlasted their statutory time limits in exile, meaning that he is and always will be an alleged rapist.

So — as free speech heroes go, Assange is a problematic candidate. His actions, motivations, history, all open to serious questions which nobody has been able to ask him for many years.

Does that mean he is not deserving of either the protection of his government or the defence of his craft?

That is also problematic. WikiLeaks broke new ground, but mainly in volume and approach, not content. Leaks of classified government material are as old as journalism, and their publication conventionally acknowledged to be journalism. WikiLeaks applied no discretion to its dump; it did not, as most mainstream media would have done, hold back material which might be actually damaging to national security or endanger lives. It was its indiscrimination which called into question whether it could call itself a journalistic pursuit.

That’s a fair question for debate, but frankly the US justice system is a dangerous place to have it. Australia should be giving more serious consideration than it has so far to whether its citizen should be subjected to that risk. It should also be wondering whether justice is still playing any role at all in the Assange saga, or if it has become pure politics, calling for a diplomatic way out of the mess.

The truth, it appears to me, is that there are no heroes in this story. I see little reason to sympathise with Assange’s situation, but I also think the legal process dragging interminably around him has little integrity either. It is, the whole thing, unedifying.

Michael, can you confirm that you carried out due diligence in providing us with this statement “WikiLeaks applied no discretion to its dump”? I recall that WikiLeaks went out of its way to work with a number of media agencies to avoid exactly that of which you accuse them. At least the dump that was so profoundly in the public interest and most embarrassing to the US.

Normally love Michael’s work, but I too think he has come up a bit short here….Assange knew very well that he was poking the bear really hard and repeatedly and what the consequences would probably be, but still chose to do it because of the public interest – and all those media agencies agreed with him until it got too hot for them and they threw him under a bus.

That courage continues in the face of abominable pressure, and that qualifies him as a hero in my book.

The magnitude of the US/UK/Aus malfeasance he exposed probably qualifies him as one of the world’s greatest heroes.

i remember the same thing – WikiLeaks did their due diligence, only for some news outlets to meet things up – wasn’t it the Guardian that “accidentally” published a password or some such?

Yes, it was The Guardian.

Yes, my recollection is the Guardian editor wrote a book (cashing in on the info made available to him by Wikileaks, thankyou very much) disclosing the secret password. Assange then made it all publicly available, since it was already publicly available anyway.

As l remember, JA told the Guardian journalist the real password, which the journalist published assuming it was false.

The password was fairly complicated therefore logic would suggest it was genuine.

But hubris took hold – Peston has to show that he was a player, if only in his own tiny mind.

So that the hack could do further research on the details not for publication.

Sloppy, pusillanimous & treacherous.

Yeah I agree, I generally find Michael to be thoughtful but he’s fallen for the propaganda here.

Is this a new ‘Michael Bradley’, or has the old Michael Bradley left his sagacity at home when he wrote this piece? This is the sort of ‘balanced’ article one would expect from an establishment-apologist like the BBC.

The rape accusations are a furphy. Assange was interviewed about these before he left Sweden, and the Swedish prosecutors could easily have travelled to the UK to further interview him, as Assange offered. To extradite him to Sweden for questioning was so transparently a cover for extradition on to the US.

‘His actions, motivations, history, all open to serious questions’ – since when do liberal democracies put someone in indefinite solitary confinement because we don’t like what they do (embarrass the Democrats in the US)?

Where are the examples of people who have been harmed by the unredacted release of these secrets (first released by the editor of the Guardian releasing the password anyway)? I’m sure if there were any, Assange’s establishment enemies would have screeched about it incessantly.

And Michael missed the most obvious legal issue – Assange is being extradited to the US for breaking a US espionage law from WW1 when he was not a US citizen and the alleged crime was not committed in the US. Even a bush lawyer like Barnaby Jones can understand that one.

As a Crikey commenter sagely mentioned recently, the Wikileaks platform (providing an untraceable mechanism for whistle-blowers to tell the rest of us the dirty secrets of the rich and powerful) is the biggest threat to the stranglehold that the rich and powerful have over the flow of information since the invention of the printing press. That’s why Power has to malign and exterminate this very real threat. It’s a pity Michael Bradley and Crikey seem to be joining in.

I came here to say all of this but you’ve summed it up perfectly already. I will add that the statement “I see little reason to sympathise with Assange’s situation” is a weird conclusion to draw after arguing Assange is being extradited for performing journalism. I see nothing but reasons to sympathise with Assange’s situation.

Talking about putting operatives in harm’s way, how could you do a better job of that than Howard did with our troops in Iraq, or Biden did with afghan allies in the way he withdrew US troops?

Harm is a very relative thing by the standards of current and recent governments here, in the US, and in the UK.

Assange did did a great service to to the world at large, but because he dared to expose the duplicity and the hypocrisy that masks our great democracies, he is to be made and example of in the harshest way, as a warning to all whistleblowers and journalists, lest they be tempted to make public the truth. It is unfortunate that Australia does not have any political leaders with the integrity or the spine to acknowledge that Assange did the world a favour, and to push for a better resolution to the situation that Assange is in.

I am very disappointed with Albanese’s response, but I have to give Barnaby Joyce some rare credit.

His analogy this morning was very apt – If an Australian journalist here on aussie soil, insulted the Koran and a foreign Muslim country demanded his extradition to face sharia law- would our government dutifully render him up?

It’s a sad day when we have to admit that Bananaby has it more correct than most of the the rest of the Canberaa inmates, but he deserves the credit on this one.

“Stopped Clock Sydnrome” preserved, not in aspic but alcohol.

Don’t be too certain – what if oil was withheld until we complied?

Anyone want odds?

What this whole sorry stuffed up scene represents to me is the value of being an Australian citizen. Unless you have money or are a sports star or politician or someone favoured by the government and you find yourself trapped overseas because of the covid ‘epidemic’ you cannot get back in unless there is a media storm about your situation or you attract a politician’s interest because it may be politically advantageous for them. Assange is caught doing what all true journalists do which is to shine lights into dark corners so we, the unsuspecting populace, can make a more informed decision about our joke of a vote. Of course our political masters, those who love to strut the stage of the world don’t like this as their whole narrative is one of keeping us in the dark precisely so we don’t have an informed decision but one that is dictated to us by our wholly compromised media who are nothing but mouth pieces of the politicians. No wonder conspiracy theories abound!

To my mind, being an Australian citizen has about much value as being a citizen of China, Russia, Venezuela or any of the demonised countries which we have been told to be afraid of and I wouldn’t mind betting that they have equal if not better rights than us. And the whole lamentably sad aspect of this is that we, as a society, become alienated from each other thus being pushed into fringe groups that give solace to the alienated. The Assange issue has proven to me that there is very little probity within society and the worse it becomes for him, the more alienated many will become. I also agree with some, not in the MSM, who suggest should Assange die (a la Epstein?) in a US jail, then there will be an almighty backlash against those who allowed this to happen. What a clusterfck! He dies and there may be strong desire for change? What an appalling cost to pay.

Finally, Mr Bradley, you make the statement that “According to a lot of accusers, including the US Senate, Wikileaks actively cooperated with Russian security services to interfere in the 2016 presidential election. Specifically, it released emails stolen from the Democrats, with the evidence strongly pointing to Russia as the thief.” However, a group of ex US Intelligence agents utilised their skills with one of their group, a highly skilled technical operative retired from the NSA, timing the speed of the upload from the Democrats server and proved beyond dispute that it could only have been downloaded to a USB. In other words, there was no external hack, it happened within the DNC building. It was an inside job. You need to get out more, mate.

“We have a fabulous track record for extending consular assistance to our citizens who strike legal troubles overseas, often negotiating their way out and home”?

Hicks?

Habib?

What did “we” do for the Bali 9 – besides sell them out? How many pieces of silver, how much co-operation (re “Muslim terrorism”) did Keelty’s AFP and the Howard government get from the Indonesian government for serving them up on a silver plate?

…. Seems to depend the “jurisdiction” and need to pander?

Is it al all possible that those “rape” charges were a ruse to get at him? Considering what went on behind the scenes – as reported by various news services?

Indeed, klewso, these were the names uppermost on my mind when I started reading…let’s add a seriously talented soccer player and for the record, anyone seeking asylum in Australia ever, and the very, very many seeking citizenship and many more who are documented and paid up citizens but can’t get into or out of Australia or a response from the Department and to cap the list, all the Australian-born Australians who threaten every election cycle to move to NZ because they can no longer abide Australia. How about Aboriginal people threatened with deportation to another country? Remember Bainimarama who stood up to Dutton? Ardern also can testify to the wretched state of Dutton’s deportees arriving on her shores. Amal Alamuddin and Katie Hopkins don’t seem to have much in common but both have been allowed to visit when citizens could not. This is a list that has no end and that’s why I conclude the government has zip regard for citizenship.

Worse, because of Australia’s craven subservience to US demands, US may well carve out a precedent for reaching into the streets of any country they decide but especially those they consider friends (say, Australia) and handpicking any individual, journo or not, on some trumped up “we don’t like them so we’re gonna extradite and torture them” story. Does anyone believe they’re any different to Julian?