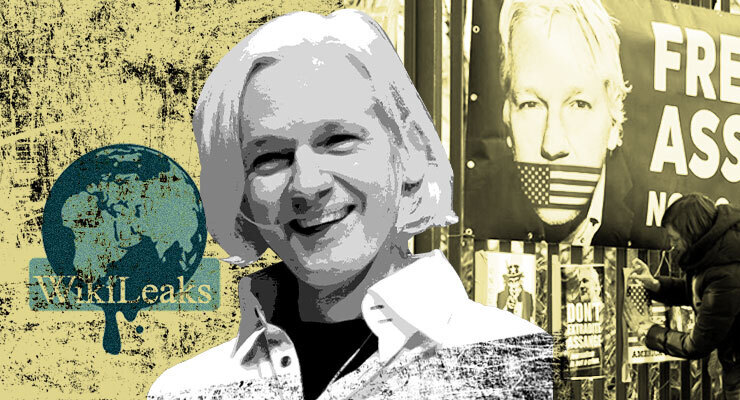

When Julian Assange was in a London court after being extracted from the Ecuadorian embassy, the judge kicking off the process that would end up with him in indefinite incarceration noted that he would then be free to deal with the extradition request from the United States. Assange, behind the full glass screen of the dock, put out two thumbs up at hip level in ironic thanks.

It was a courageous gesture, and a very recognisable one, redolent of time and place, the distant sunburnt suburbia of the 1970s and ’80s, and it got an extra laugh from the Aussies in attendance of recognition and appreciation, a final flash of the bogan-with-a-modem persona before disappearing into the system.

It was in that spirit that WikiLeaks had started out of the crucible of Melbourne, if DIY politics avant-la-lettre, lefty community radio and squatters unions, memories of the ’75 coup, and the bizarre moment when a Maoist groupuscule headed by Albert Langer was running the world’s second or third software liberation movement. WikiLeaks’ fark it taking on the American empire could only have come from Australia, possibly.

The milieux from which it emerged, the cypherpunks and Chaos Computer Club, was heavy on talk, short on action; The Guardian, which became its main outlet well before Cablegate, was burnt out and out of ideas before WikiLeaks came along, with its simple but effective “mass leak” model. Then, it was confined to single gotchas, a crooked cabinet minister here or there. After, it became the destination for Edward Snowden’s large release, and then the mass onslaught of the Paradise/Panama etc papers.

Which is of course why it is Assange who is being prosecuted and no one else. The judicial and existential terror of the US’s Kafkaesque sentences is aimed at anyone who dares to change the whole relationship of power to the global populace, as much by challenging the way in which investigative journalism was done, as to the power itself.

Thus, in defending Assange, we have had to talk in a double fashion. The first is to make the point that the US government’s application of the Espionage Act to WikiLeaks’ activities does endanger any genuine investigative journalist who works for an outfit that actively pursues new leaked material. The prosecution takes certain of WikiLeaks’ tactics — listing “most wanted secret documents” etc — as essentially being similar to cold war spy games, in which spook agencies operating out of embassies made it known they would pay good money and favours for documents. But there is no accusation of collusion with foreign powers. (None of the 2016 material forms part of the accusation.)

Instead the US Justice Department has transferred these typical state-agency actions and made them the stuff of espionage, for… who? A non-state agency? WikiLeaks wasn’t hoarding or selling the documents. Indeed it was criticised for its desire to put the most complete set of documents out there as rapidly as possible. Mehhhhh. Ask any WikiLeaks defender to be honest and they will say that going from poking the American eagle in its nest to talon-gored and pleading mental health issues is not a good look. But this has now become torture.

If some of its actions, like these “top 10s”, now look like a tactical error borne of bravado, they are not different in kind from what any major media organisation does by the very act of using them for investigative series. The greatest ad for “we want documents” is past stories using leaked documents. Every such major series is now accompanied by breathless behind-the-scenes stories of how it was put together.

At the height of WikiLeaks mania, most major news organisations — including News Corp — created leaks portals. They were in mimic of WikiLeaks’ untraceable leak portal, but they were all hopelessly compromised and soon abandoned. They were the same soliciting of leaked, i.e. stolen, documents by those sworn not to release them. Yet the 175 years pile-on on Assange is designed to emphasise that if you stay within lines — those which confirm investigative journalism as a pressure-release valve for the entire system — you’ll be alright.

What possibility of a real shift is there? President Joe Biden’s willingness to continue the Trump prosecution — after Barack Obama had discontinued it — is a measure of two types of American liberalism. Biden is to the left of Obama economically, but to the right in foreign affairs: new dealer American greatness v Obama’s more acute understanding of how the world really sees the US.

But perhaps he may be looking for a way out now. A trial, an appeal, a possible Supreme Court appeal, years of it, Assange sickening, perhaps dying on US soil? Would this be sufficient to create a rift in US-Australia relations, which would spread to the mainstream and awaken a spirit of independence last seen in the 1970s? It’s very possible, and there must surely be some thought about how this would interfere with Biden’s most forward-looking project: China-containment.

In the UK, one sees very little possibility of initiative at the highest level. Like many classical liberals, Prime Minister Boris Johnson has no problem with a national security state of arbitrary power, and if he is deposed he will be replaced by someone lacking even vestigial libertarian tendencies. If the government falls and Labour wins, the new PM will be someone who actually prosecuted Assange, so, yeah.

And Labor here? One expects it will keep discipline throughout the campaign, not let it become a national security wedge, and have little enthusiasm for it after victory. There’s very little left of Labor’s anti-imperialist left; Assange’s position — that the US’s multidimensional global reach represents the major tyranny today — is exactly what Labor’s existing nationalist left most hate being associated with. The grotesquerie of Assange’s situation will tug at some residual progressivism, but it is not going to be first, or even 10th, priority.

The public pressure must continue on governments. No one really knows when a breakthrough might occur, and a situation suddenly flip — even as all sorts of behind-the-scenes stuff is played out. The best hope for bringing the situation to a real crisis remains with the mainstream media whose project was rejuvenated by WikiLeaks.

A full page/screen, or even half-page “Free Julian Assange” by The New York Times would push the thing towards a crisis of public and state. But half a dozen newspapers/sites would push it further. The Guardian could start it. The Guardian Australia could start it, if it is run from here, not London.

One holds out little hope, but it’s the one very real thing I can imagine happening in the next weeks or months. Well, thumbs up, there’s bulk possibilities, even though the situation is rank. We’re all stranded, some worse than others.

Assange may be a bit of a ‘bastard’ but he is our ‘bastard’. Wise words from the past follow:

First they came for the Communists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Communist

Then they came for the Socialists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Socialist

Then they came for the trade unionists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a trade unionist

Then they came for the Jews

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Jew

Then they came for me

And there was no one left

To speak out for me

Pastor Martin Niemöller (1892–1984) tends to be quoted here frequently.

End Times?

Good times. In those days, “pastor” did not mean Pentacostal f*scist wing nut.

I did notice that Pastor Niemöller didn’t mention Pentacostal folk. .

He survived their ideological & spiritual (sic!) forebears by 40yrs – their ilk would be beneath his notice.

Timely reminder A, but we’re talking here about the US, UK and especially the Aust govts who, despite their faux christian values, frankly don’t give a sh*t about Assange or human rights. And for that matter most of the world press to whom your comment above should resonate sharply.

“The Guardian”?!!! – weren’t they very much involved in throwing Assange under the bus in the first place?

Up to their eyeballs.

Only by freeloading on his courage then, through carelessness failed to redact a doc they published.

Then blamed him for that culpable incompetence.

And they wonder why a decades long supporter refuses point blank – though I respond to the constant begging letters – to any longer fund them.

Any word from that Peter Greste character, whom the legit. press fulminated over until finally released from an Egyptian prison on trumped (sic!) up.

A fraction of the time, just over year, Assange has endured…but crickets since this piece in January,2021 –

“I have argued Assange did not apply ethical journalistic practices and standards to his work more broadly, and therefore cannot claim press freedom as a defence.

Soon after he published unredacted US diplomatic cables in 2011, a wide range of news organisations distanced themselves from WikiLeaks for that reason.”

There are several names for people like that, in Norwegian,French, Italian and other unfortunate countries.

Link posted separately, for fear of the madBot.

Gresten – https://mumbrella.com.au/julian-assanges-extradition-victory-offers-cold-comfort-for-press-freedom-663208

Here’s a wishful scenario: Prime Minimal Morrison takes a Xmas holiday (likely not to Hawaii) whereupon Acting PM Barnaby Joyce does a deal with the US not to pursue Assange. It could be the single memorable act of Joyce’s political career.

More memorable than giving $80m of taxpayer money to his cabinet mate Angus Taylor and his tax-haven arms length company for water that was never provided? I doubt it.

You really think the US gives a fig what we think either way? They want Assange dead and that’s what he’ll be if he ends up in an American jail. He’s barely surviving the ‘humane’ English jail system, there’s no way he’ll survive the murderous, sorry, suicidal, US system.

I don’t think the US cares one iota what we think. But in view of the latest AUKUS pact they may decide to throw us a crumb if asked ‘nicely’. We are merely a military & surveillance base to them, a fact which Oz PMs (of all colours) fail to understand.

They’ve effectively destroyed him psychically if not, yet, physically and real estate, especially handy to their hemispheric interests (see comments passim), could be a better bargaining chip.

Not that either of our wholly owned subsidiaries would dream of calling it in.

A “free press” should and would.

Australia is the junior partner in the AUKUS alliance. The added complication of US and UK involvement in the Julian Assange case are an additional obstacle to overcome in order to achieve a fair and just resolution for him as an Australian citizen.

Agree except it’s the USUKA Alliance.