Not many journalists saw that coming! Criticised last week for prioritising Liberal-held seats when allocating his government’s multibillion-dollar grants programs, Scott Morrison did the unexpected: he told the truth.

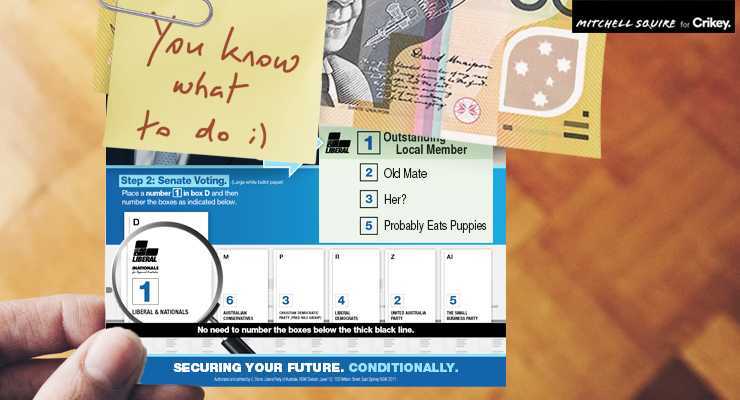

But before we get too optimistic that we’re seeing a new era of open government, what actually happened was this: with a twist of truth, the prime minister both spiked an embarrassing journalistic exclusive and normalised the rort into an electoral plus, particularly in the conservative electorates facing “Voices of” independent candidates.

It came straight out of the populists’ playbook. Don’t hide corruption. Brag about how you’re delivering for your mates… er, “voters” while punishing your opponents.

For accountability journalism, it’s existential. If deep investigations can’t shame governments and drive change, what’s their point? It threatens democracy, too: when voters endorse the rort, it entrenches the practice.

In this case, Morrison didn’t have to tell the whole truth with all its ugly details of electorally coded spreadsheets and prime ministerial interventions. He just had to sprinkle enough truthy magic over otherwise inconvenient facts. And so, with a laugh-off attributing the grants to having “a very good local member”, Morrison confirmed the strong journalism that Nine masthead reporters Katina Curtis and Shane Wright had spent months digging through reports to reveal.

For journalists, it seems Australia has now caught up with the United States, where a similar Trump truthy play in 2017 triggered the Twitter meme: “I chased this story for a year and he just … tweeted it out.”

Curtis and Wright combed through publicly available data to demonstrate what both the press gallery and Labor have been chasing since Morrison became PM: that discretionary grants overseen by ministers and MPs go overwhelmingly to Liberal-National Party electorates.

They found as they looked through more than 19,000 grants that $1.9 billion went to Coalition seats, compared with $530 million for Labor seats over the three Morrison years.

Finance Minister Simon Birmingham tried to muddy the waters with a “selective analysis” here and a “regional grants” there. But Morrison cut through all that. His pugnacious “good local member” response confirms the truth that matters: grants are being awarded not on the basis of need, but of politics. More, the reward/punish divide is central to the design.

Standing in suburban Brisbane, Morrison was happy to embrace the dichotomy between Liberal-held Dickson ($43.6 million) and neighbouring Labor-held Lilley, which got less than $1 million.

As Jan-Werner Müller wrote in What is Populism?: “Populists always distinguish morally between those who properly belong and those who don’t (even if that moral criterion might ultimately be nothing more than a form of identity politics).”

In the short term, the truthy play denied the story the sort of traction it would once have received, turning it at worst (from the government’s perspective) into they-say-this, they-say-that stream that bores the audience into turning away. Nine tried to keep the story going with its in-depth reports, but by the weekend it had faded.

It’s a result that will ensure future stories about political bias in grants will be found just less newsworthy. Already by week’s end, the $15.9 billion decisions “taken but not yet announced” slush fund revealed in the mid-year budgetary outlook had morphed into the anodyne “election war chest”.

In the medium term, Morrison is grabbing the opportunity to pose the old quiz show money-or-the-box choice to electors. What do you want? $40-odd million in the hand or (rolls eyes) “good governance”?

Morrison is banking on the assumption that many voters — particularly low information voters who can turn elections — think this is the way that politics has always worked. But the overt politicisation of grant allocations marks a decade-long normalisation of the rort.

The conversion of needs-based government grants into political slush funds marks the transition from the privatisation of public services model of late 20th century neoliberalism to the plundering of public assets for political gain of 21st century populism.

The moment it became baked into Australian politics? Perhaps the NSW ICAC’s Berejiklian inquiry, when rorting for political gain became an acceptable defence to shrug off favours for a boyfriend.

With this week’s pivot, Morrison is working to transform the 2022 election from a contest of ideas to an electorate by electorate scramble for dollars.

Sure, success would degrade Australian politics for the long term and gut the higher purpose of accountability journalism, but he knows a harder truth: electoral success cleanses all sins.

Who knew there could be a bigger, smellier skidmark of a PM than Abbott?

Maybe the Labor held seats shouldn’t pay taxes then.

Truthy – not a word I’ve heard for a while, but totally applicable to everything this appalling excuse for a government does.