Although independent MP Zali Steggall justifiably copped a torrent of criticism yesterday for her non-disclosure of a $100,000 donation, at least she fronted up to the media to defend herself.

Ask any major party politician about a donation and you’ll get the bland response that it’s a matter for the party organisation, not them. Or, in the case of former attorney-general Christian Porter, a blank refusal to acknowledge any issue.

The focus on Steggall has been around her failure to disclose. Few outlets — including Nine newspapers, which broke the story — went any further with the issue. Nine, of course, is a serial political donor itself, mostly to the Liberal Party, and has hosted Liberal Party fundraisers. Indeed it is doubly conflicted because as a media outlet it is the primary beneficiary of political donations and taxpayer funding of political parties via advertising.

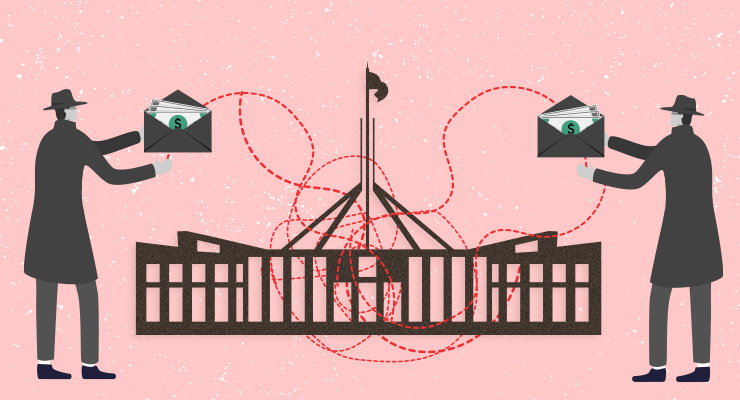

The mainstream media is certainly much better at probing the lack of disclosure of political contributions than it used to be, which is a good thing. In particular, they’ve become aware that the origin of large volumes of money within political parties is never disclosed. But disclosure and the lax rules that relate to it are only a smaller part of a bigger problem. It is the entire system of political contributions that needs remedying. Disclosure only provides some greater transparency into a fundamentally rotten system.

It’s not in the interests of media companies, the main beneficiaries of that rotten system — especially those with broadcasting interests — to question it. But knowing — partly — who is paying to influence policy via political contributions isn’t the same as stopping that process of influence-peddling altogether. As Michael Yabsley said yesterday: “The only option is to put the broom through the whole process of political fundraising and election funding in Australia.”

Plenty had a crack at Yabsley in response, given his history of involvement with political fundraising. But he is literally the best person possible to pursue the cause of political funding reform, because he knows it better than anyone. When Yabsley says political contributions are about pay-for-play, you better believe him. It’s not just some journalist or commentator telling you. He’s been in the room where it’s happened, hundreds of times.

Better disclosure laws are fine — and some states such as NSW and Queensland are already way ahead of the Commonwealth. But the bigger battle is ending the whole pay-for-play game of political contributions entirely.

That doesn’t merely mean ending contributions made via fundraisers with ministers and opposition spokesmen and women, which are the primary mechanism for Australia’s two-speed democracy. An individual or a corporation or a union could make a large contribution to a political party or candidate unrelated to any fundraising event, and entirely motivated by altruism, but the exchange contains within it the potential for future influence, even if only because a politician is more likely to agree to meet a donor than an ordinary member of the public.

So it means ending all but modest donations from individuals.

Moving to a system of contributions at a level that is unlikely to distort decisions about policy or access is the only way to end the two-speed democracy we’ve created via contributions to political parties. Indeed, it would force political parties to engage with voters in a way not seen since television transformed election campaigns in the late 1960s.

It would dry up tens of millions in free revenue for media companies, but better to prevent influence-peddling than to only learn about it later — sometimes years later.

Costello’s 9 “An Audience with Jenny Morrison” fun raiser stunt Sunday night?

How much would that sort of political PR/advertising have brought on the open market?

The answer is so obvious. If it was going to change it would have already. Corruption is only bad if your not in on it. No one is complaining.

This is a reasonable proposal. “One person, one vote” philosophy should apply to how parties fundraise.

I would go even further to require the AEC and the State Electoral Commissions to collaborate on a centrally hosted revenue management system for parties. All parties would only be able to record revenue received through a transparent portal such as via MyGov, and monies received be published immediately once a threshold is exceeded, and donations optionally linked to donors’ Tax Records in real time.

This would make the system harder to fudge or stuff-up, and make life easier for the Electoral Commissions auditing revenues.

I think that Bernard’s essay is balanced and fair (as usual). As he notes in today’s article “Plenty had a crack at Yabsley in response ….” (to comments attributed to him by Bernard in Bernard’s article in yesterday’s edition of Crikey). I was tempted to remark on that fact yesterday but I decided, for better or worse, (probably the latter), to let it go.

I thought that some of the comments that I read yesterday (no doubt posted by members of the Crikey Labor Club, who display a political mindset which indicates a level of sophistication no deeper than “Dahhhh, Labor Good, Liberal Bad”.

As Bernard says today, “he (Yabsley) is literally the best person possible to pursue the cause of political reform, because he knows it better than anyone”.

I am prepared to accept Bernard’s judgment on that until or unless someone can present me with some compelling evidence that I should change my mind (by the way, that phrase “change my mind” might be something the Crikey Labor Club members could have some trouble understanding).

If we aren’t allowed to know in real time from who the donations come, then nor should the parties. An (interim) solution might be thus:

Really there is no excuse for not having real-time disclosure, but that does not dismiss the influence aspect without open diaries etc.