In 2001, John Howard faced an unwinnable election, polling as low as 43% in two-party preferred. Petrol prices were through the roof, cost of living was a key issue after the rocky introduction of the GST, and the government’s policy chops were being questioned on many sides.

Sound familiar? Howard even had to deal with a message scandal: a memo from Liberal Party president Shane Stone to Howard, which suggested the government was “mean” and “out of touch”, was leaked to Laurie Oakes.

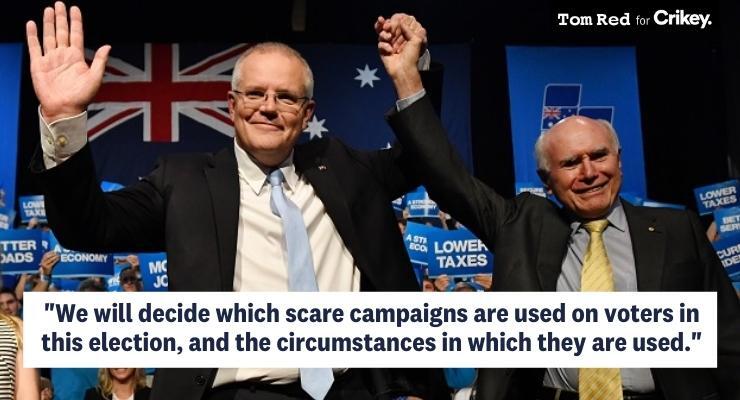

Morrison faces similarly bad odds and, like Howard, has little on his record to buoy an election campaign. But Howard managed to pull off an 11th-hour turnaround on the back of a national security crisis, and if Morrison wants to do the same, he’ll be looking to Howard’s playbook for a few tricks…

How to win an election in 90 days

Step 1: Capitalise on ‘uncertain times’

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times… or so Morrison wants you to believe. The economy is great, things are good at home, but a foreign threat lurks. In 2001, Howard capitalised on the rescued asylum seekers aboard the MV Tampa to appear tough on border security. He gained two points in the polls as a result.

His stance was brought home when 9/11 happened a month later, and the threat of terrorism made his infamous election pitch irresistible to frightened voters: “We will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come.” This stance gave him a five-point recovery in the polls, just in the nick of time to win the November election.

Morrison is already trying to engage a similar strategy — about the threat posed by China. He repeated Howard’s mantra of these “uncertain times” extensively in Parliament last week, but his attempts to paint Labor as Chinese Communist Party (CCP) sympathisers ranged from tenuous to straight up hypocritical.

Now the unfolding situation in Ukraine will likely provide a redirect for a national security election. The threat of “a new world order” led by allied superpowers Russia and China may provide a more tangible element to Morrison’s pitch.

Step 2: Pull off a stunt

The “children overboard” affair saw immigration minister Philip Ruddock claim on the eve of the election campaign that asylum seekers on a boat off the coast had threatened to throw their children overboard. The claim was later found to be false, and evidence suggested the government knew this before the election. And yet this political stunt sealed the deal for the tough-on-borders strategy.

Desperation could lead to Morrison making a similar play to convince Australia of the threat he is trying to sell.

Step 3: Play the strong man

Howard painted himself as the stronger candidate, more capable of facing up to the international threats than the weak alternative provided by opposition leader Kim Beazley. We’ve already seen this play utilised extensively to discredit Anthony Albanese, and it’s no coincidence that the term “little” was tossed across the floor in Parliament last week, with allusions even made to Albanese’s shorter stature.

Will a national security ploy still work in 2022?

Times are a-changing, and 2022 is a very different world to 2001. Even if Morrison sticks to the playbook and makes it work, there’s no assurances Australia will respond in the same way.

Mark Kenny, a professor at ANU’s Australian Studies Institute and a former journalist, says there are a few key differences between now and then. While Australia is still looking for a strong leader to get us through the hard times, Morrison’s character may have been too damaged for him to be that source of comfort.

“He came in with almost no agenda, other than tax cuts. And we’ve seen a succession of negative stories that reflect poorly on his personal character.”

Kenny also thinks it won’t be as easy a ploy to pull off this time around: “Labor is much more attuned to this now, and is being very careful to remain in lockstep with the government. And that makes it harder for the government to articulate a separate position and to prosecute the argument that Labor is somehow weak on national security.”

Finally, while Morrison will be attempting to capitalise, this situation is still largely unknown. While the world had never seen an event like 9/11 before, the Ukraine crisis has been bubbling away slowly for years.

“Depending on how the situation unfolds, the government is in danger of looking shrill as we saw last week when they risked the bipartisan position on China. But if the situation remains perilous, and if Morrison can get people to link Russia and China together, there’s a possibility of leveraging this politically.”

But whether it works or not, Morrison’s pandemic failures and lack of agenda mean the Coalition might not have much of a choice.

As Kenny puts it, “whether it’s a good strategy or not, it’s almost the only strategy they’ve got left.”

When ScoMo’s calling Albo “weak”

hypocrisy has reached it’s peak,

for he’s just run away to hide

when journalists have vainly tried

to get him to apologise

for all the weasel words and lies

designed to allocate the blame

to someone else so any shame

can never threaten his career,

for that’s the thing he holds most dear.

He ducks and dodges, twists and turns,

consumed by narrow self-concerns,

and now he’s donning combat gear

as camouflage to ramp up fear,

pretending he’s a big, tough guy,

as Howard did in years gone by,

but this time the attempt should fail

for Morrison can’t draw a veil

across the flow of grim reports

that detail cock-ups, scams and rorts.

Good one!

Gazza

Brilliant as always.

Surely Australia won’t make the same mistake again? Scotty and his wretched government are destroying the joint. They are not there for the good of the Australian people, they are there at the behest of big business mates as well as to feather their own nests.

The Liberal party is quite literally tearing itself apart in NSW and federal Libs all hate each other. You know the old saying…”If you can’t govern yourselves, you can’t govern the country”.

We need change.

Morrison has no standing as a leader in the region or the world- how could they trust him? Ask E Macron. But of course he will big note himself, lie and do anything to promote fear. Just how easily conned some Australians are we will find out.

B-b-but, but, AUKUS. Aukus!!

I read somewhere in the media this morning that the AUKUS deal has not yet been signed, apparently to the disappointment of the Aust Govt. Mind you, that could be the rabbit coming out of the hat in early May.

Yes, the Lying Nasty Party and its enablers, NewCorpse et al. excell in rabbits and other such sleight of hand political chicanery.

I prefer USUKA. It gives an indication of the relative importance of the three countries involved.

That gives the truth to the real meaning of such a so called “alliance”

And its ‘intel’ arm, the 5 Ayesoles.

I thought Tony Abbott was an embarrassment to Australia. He almost rates as an incompetent leader, almost. Then along came Scotty, who is in a category of his own. The man has no substance and to call him incompetent is a high praise. He is the leader of the most corrupt government partnering with big business ever.

We must have/DEMAND change.

Will the need for change trump rotting pork-barreling, and $ 100 million dollars worth of Clive’s preferences?

I reckon there are some fundamental differences between now and then, that aren’t going to work in Scotty’s favour.

the main one is that Russia v Ukraine doesn’t hit home in the heart of the Oz public anywhere near as much as 9/11, imo. For Australia to feel involved, it needs to be a direct conflict involving USA or UK, or action against Oz directly. That’s why Scummo has spent so much time focusing on China.

Another significant difference is Morrison’s performance. Howard’s standing might have been flagging in 2001, but I cannot remember his overall performance and the performance of his cabinet being anywhere near the clown show that Morrison has staged during his tenure. Morrison is closer to Billy McMahon-quality than Howard ever got, imo. Morrison’s troupe are an extraordinary freakshow of grotesques, boozers, sickos and tinfoil hat wearers. it really is a strikingly odd menagerie he’s attracted. And they are all, like the ringmaster, non-performers.

Howard was seen as mean and tricky by some (like me, i couldn’t stand the little pr#ck), but a lot of people felt he was an earnest conservative who could articulate a position well. I think this is true, even if listening to him used to make me tear my hair out, like being lectured to by an ultra-straight grandpa. Morrison’s rhetoric rings hollow, contradicts itself often without any attempt to nuance the about-face, and his branding as a liar has stuck fast. Merci Macron!

Albanese staying so close to Morrison on so many issues, has made it very hard for Morrison to accuse Albanese of anything, without exposing himself to the very same accusations. Remember the Howard to Beazley “got no ticker” remark? Bit hard to do that with someone who’s shadowing your moves, and looks to be physically in much better shape also.

There’s probably more reasons, but this lot will do in seeing Scummo doesn’t get the lift out of this current Russia/Ukraine crisis that he’s hoping for.

So the only miraculous path to victory available to The Liar From the Shire is more of his destructive bulls*t? Can someone explain to me exactly what benefit it is to the citizens of Australia, as distinct from dishonest and greedy business, for this vacuous buffoon to win another election?

Time for a real miracle :- The demise of this mendacious, duplicitous Morrison government – because that would be a real godsend.