Your correspondent got some pushback earlier this week on the notion that the Russia-Ukraine war had left NATO “screwed” — by which I meant that its capacity to project power beyond itself had been called as a bluff by the invasion.

That, it must be said now, was somewhat of an assessment of the old NATO — the Anglosphere Atlantic power with West Germany at the front (France was partially or wholly out from 1959 to 2009, for just that reason), Turkey as an outlier, and against a global bloc who represented (however willingly) an entirely different approach to social life, both lined up, nukes to nukes.

Now NATO seems to me to be such a complex, sprawling beast that any clear mission that is purely military would be wreathed in levels of politics. But it’s also clear, as some noted, that it has renewed its purpose along defensive lines. Ambiguity is still possible where clarity matters most: what if Putin or post-Putin Russia were to take the Baltics? Is there a core and periphery NATO? Though a European defence organisation shorn of US and Canada would be a more genuine defence organisation (and will not happen), the Western solidarity movement with Ukraine has coalesced around an allyship that has little time or place — save among a few commentators — to also target NATO expansionism or imperialism, or even much comprehend it.

Many thousands of progressive people have leapt into action, effectively fusing their social progressive politics with a geopolitical take in the same spirit. That has had two quite consequent effects, one of which is to utterly marginalise any genuine anti-imperialist discourse in Western societies. But the other is one that resituates left and right fundamentally with dire consequences for the latter — a shift the right appear not to have understood yet.

Thus the small avalanche of op-eds and takes from the Australian and UK right trying to create a clear cultural frontier between left and right over the war, and claiming both that Western weakness and decadence, on matters of green politics and trans politics, etc, has emboldened Putin to invade Ukraine, but also that we will have to become far more like Putin’s Russia if we are to defend ourselves from the threat to Western civilisation represented by Putin’s Russia.

There’s Tony Abbott doing his wise old man schtick, Janet Albrechtsen talking about Pollyanna politics of the West, ASPI’s Peter Jennings warning that Biden is too soft, and Peta Credlin essentially repeating the line in her column, with Peter Dutton presumably to follow. Only the right can embody the West in that account. Progressives are a fifth column.

What the right do not seem to realise — or are simply trying to ignore — is that the old notion that the left and progressives always side with the West’s enemies has not only been stood down in the Russia-Ukraine war, but has been entirely reversed. The political division they wish to capitalise on — in which a right defends the virtues of Western civilisation despite its flaws, while the left “obsessively” seeks to find the West in the wrong — has now almost completely disappeared from even the broadest conception of mainstream politics.

Across the Western world, the people getting out into the streets to support Ukraine, and to insist on a simple rights-based account of its political autonomy as a state, are the people who normally organise demonstrations in the streets: the progressives and the left. They are the ones defending the notion of a virtuous West. This as opposed to the right, which is split three ways, between a mainstream right which wants to claim the “Western champion” tag, a realpolitik right, which, in simply looking at how states respond to threats, cannot help but concede that NATO’s overextension is a primary casus belli, and a cultural paleoconservative right (stretching from respectability to white supremacists) who threw in their lot with Putin years ago, as a preserver of Western Christendom in exile, anchoring it until it can be restored in the nihilised West.

This mainstream conservative right — the Credlins, Abbotts, etc who argue that the Mardi Gras caused the shelling of Kyiv — is trying to restore an old Thatcher/Reagan politics in which support for pro-Western geopolitics was fused with a support for pre-1960s traditional Western culture, centred on the religious and modest nuclear biological family, joined together with others through national patriotism. This conception was accurate enough at the time, since the post-WWII left had evolved a complex politics in which global anti-imperialism had become twinned with libertarian cultural politics at home.

But since Mao’s great victory in 1949, global left hopes had been borne by nationalist and peasant forces, who were explicitly socially conservative. The Algerians, Viet Cong and Palestinians would not be attending Orgasmopol Happening ’72 in Amsterdam anytime soon, and some were actively repressing personally liberated women, gays and lesbians, artists, “bohemians”, etc (though the global alliance did shift that somewhat in many places).

Something of this strategy and split hung around the Western left right up to the end of the global anti-capitalist movement of the late ’90s/early ’00s. In those demonstrations there were still radical unions whose members had fairly traditional social values, Communist parties supporting ghastly regimes, all linking arms with those seeing DIY transformations of gender/race/sexuality social issues as equally important.

But by the time Occupy came round in 2010, this fused politics had more or less disappeared. Why? Partly, US imperialism had destroyed itself as an authoritative player with the Iraq debacle, the farce to Vietnam’s tragedy. Moreover, capitalism had become so distributed as to have no frontier, less B52s and GM, more Starbucks and Foxconn. China’s entry into this world cultural system meant that there was no plausible countervailing power.

Occupy was concerned with the growing inequality and destructiveness of capitalism within the West, not by it, and this melded easily with the next stage of social politics, an acknowledgement of the equality of proliferating identities. The Occupy generation was now pushing for the West to live up to its claims of democracy, liberty and freedom to flourish. Crucially this marked the end of attachment to a militant present third world, and a re-attachment to the politics of colonialism (past event, present spirit), and the substitution of indigenous peoples for militant peasantries — often with a shift from solidarity in struggle to a revival of “noble savagery”.

In the decade since Occupy rose and fell, the social grouping that had borne forward this energy for half a century — now, the knowledge class — had come to the centre of social and economic life and rapidly reconstructed the content of its institutions. However resisted by brown energy and other interests, the institutions of society have become vehicles for green energy, for the pluralist celebration of identities, all drawing on secularised Judeo-Christian notions of the right to flourish within a peaceful society.

It’s true that the ’70s version of the new left was “anti-Western” in many ways, in that it sought an explosive anarchy in sexual extremism (from BDSM to the “sexual liberation” of 12-year-olds), the violence of red terror, deep green communalism and the like. By the 21st century, as its class took power, it turned on a five cent piece, and advocated same-sex marriage, censorship of “unsafe” texts, and social control through an enforced moral order prioritising protection over risk.

That has left the mainstream cultural right in a terrible spot, because there is now no major social force advocating the anti-Western ideas they seek to organise against. There’s no hard-left cell left in the Labor Left; the Greens are standing with Ukraine; Socialist Alternative and other far-left groups are denouncing the dual imperialisms of the West and Russia, but crucially, not representing the latter as an anti-imperialist force. Even the goddamn Communist Party of Australia (Marxist-Leninist), the old Chinese tankies, won’t stand with Russia. There’s no bad guys to turn the attention of the mainstream to.

Indeed, this is where the trap that the right backed itself into snaps shut. Taking an ancient notion of decadence as demasculinised, unassertive, not single-minded, unwilling to dominate nature (a sort of protein bar version of Nietszche), they’re trying to construct progressivism as 1972-style spliff-addled playpower. But if a certain discourse of fragility has arisen in progressivism, it does not equate with a lack of drive to public action.

It’s the progressives who march and organise. Would that amount to a progressivism willing to turn towards territorial war? Not yet, I think, and never of the cannon fodder kind. But hi-tech smart war in defense of the West, in its progressivist form, against societies who aren’t like that? It won’t take many years before that enthusiasm appears on the progressive left — perhaps akin to the way imperialism became a liberal cause in the 1860s, after earlier episodes of pure brigandry and theft fell away. It’s mainstream right-wing voters who are disengaged from such purposefulness, by the appeal of private life, Netflix and negative gearing, the anti-lockdown crowd not really mainstream material.

Now its cultural politics appears to be in exile from the mainstream, propped up only by News Corp in print and Sky after dark. Whatever sort of rightist he is, Scott Morrison is not this Spenglerian kulturpessimismus type, and it was precisely to head off the possible continuation from Abbott through to Peter Dutton that Scotty from the suburbs was selected. Nor has any groundswell developed around Dutton as a personification of such a spirit.

There is now no public space, I think, to launch a successful mainstream politics attacking Western decadence — but this is for the melancholy reason that there is now no substantially anti-imperialist discourse alive in the West, one willing to say that, in the last instance, some grisly characters and regimes nevertheless have a case.

So, where once leftist parties would have seen Russia’s de facto resistance to anti-imperialism as worthy of “support” (at least by non-condemnation), and Ukraine’s suffering as just part of the great clash of a world revolution, I suspect much of the passionate pro-Ukrainian advocacy among progressives is coming from a fusion of liberal-democratic values around state sovereignty, with the moral energy of anti-colonialism. It is that fusion that is giving it its extraordinary force.

That leaves the mainstream cultural right absolutely nowhere to go in their attempt to regain cultural hegemony of this process. For they are attempting to summon up that part of the Western spirit that Russia is expressing — the courage to kill and die, the strength to not be cowed by taking the other’s viewpoint — in order to oppose it. They are willing to concur with Putin on Russia’s non-European character, in order to stage a clash of civilisations for the revival of the West. Whereas the Western pro-Ukraine movement is condemning Russia for acting badly within the rules of a rules-based order it now asserts as universal, and having no real origin, history or interests.

That is the moral argument that channels the progressive energies accumulated from a decade of social-cultural struggles within Western societies to the geopolitical frame. It is capable of being drawn back into naiveté, sentimentality and kitsch, but on the other hand, it may represent the moment of a great political-cultural crossover, epochal.

And here is the great, great irony of it. In taking up such a geopolitical cause as a question of right and identity, with no reference to the actual politics that preceded the event, progressivism becomes an agent of disguising Western interests with a force and reach that earlier Western agencies — from UNESCO to the World Trade Organization — can only dream of. Reaching across the world and back into contemporary Western societies, it ensures that the absence of any anti-imperialist current in the West splits the world into two great geopolitical camps, with the US-UK-NATO supremacy now capable of spruiking a human rights geopolitics almost with a single voice.

Meanwhile China, India, Russia and various global southern states form a bloc whose narrative tells a wholly different story (India’s membership in “The Quad” is already coming apart, one might suspect; it seems ad hoc and provisional, with the Modi government quickly reasserted a solidarity with China and Russia in this episode).

What would be interesting about a deepening Russia-China-India alliance is that it would align the old Communist bloc with two colonised or subordinated megastates, giving a unified narrative to their shared historical journey, while also taking up most of the “world island” (i.e. Eurasia) from old geopolitical theory. That leaves a declining US and UK on the periphery. There must surely be a strong motive for India to throw in its lot with the centre. At which point the world is two massive camps and the deterritorialised movement once known as global anti-imperialism may for a time disappear from the world.

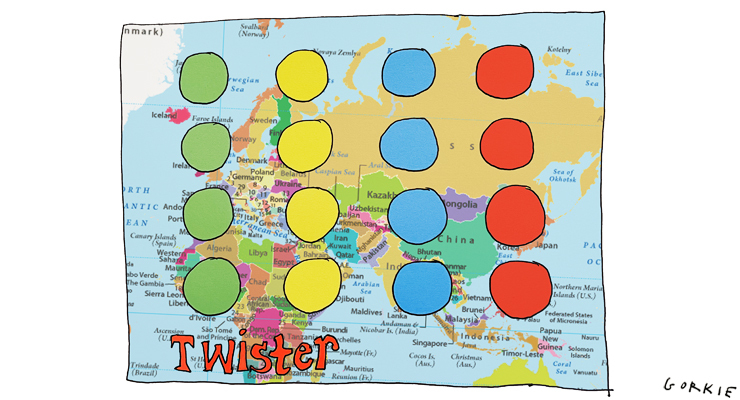

With these momentous shifts underway, Western culture wars may look like the product of a historically becalmed period and the right’s culture war even sillier and more irrelevant than usual. Looking ahead further, NATO would either be broken down into its parts, or draw in all the nations of the periphery. A sort of Oceania versus Eastasia. Oh dear.

An interesting summary. This may well be an important stepping stone towards some understanding of what democracy really means. I have long been of the view that the version of democracy which came about post enlightenment is so much in its infancy that to pronounce it is settled or that we even understand what we are in the middle of is absurd. It has been such a breathless ride for humanity since enlightenment scientifically and socially. When you think about the changes that we have adjusted ourselves to personally and as communities it’s quite astounding. I was always rather taken by the reply of the Chinese premier Zhou Chai who, when asked about the effect of the French Revolution, said ‘too early to say’. Alas, I have recently learnt that he had in fact been asked this question about the 1968 students revolution. However I do think he was also correct had it been in reference to the revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries.

I have spent some time with people from Eastern European countries through an involvement with Open Society (I raised my eyebrows when I saw a reference in an earlier Rundle article to Open Society as some sort of agent of change acting lockstep with the US government. The far right like to blame Open Society for the BLM movement. Both accusations are rubbish and totally misunderstand how Open Society works.). I have no doubt they do not see a future for their countries which involves Russia. Naturally spending time with English speaking people who are involved in organisations which are funded to promote liberal democratic ideals does not give one any handle on what the majority of people in these countries think. However I do tend to think that they people are the future of these countries, and at the moment they are the people standing in opposition to the far right governments in Hungary and Poland, governments which I would not be surprised at all to see go to Russia’s side in the end, no matter what they say at the moment.

In an interesting interview in the New Yorker with John Mersheimer, the interviewer pushed him on the question of what if the people of Ukraine want to live in a pro American liberal democracy? Mersheimer’s response was basically, tough. They live next door to Russia. That is real world politics. They may not have a choice. Essentially, the Monroe Doctrine. I see what is happening to Ukraine now as an important pushback against that doctrine. Would that South American countries could address this with the US. https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/why-john-mearsheimer-blames-the-us-for-the-crisis-in-ukraine

I do not for a second believe you can bomb people into accepting democracy. But what I have seen over the years is that it seems that people the world over want to live in democracies, as messy and nebulous as they are. People die for the right to vote. So in the end the question may not be ‘is democracy the way forward for the world’ but ‘how can democracy be the way forward for the world’. I think there are a lot of players in our western inclined countries who would like to introduce autocracies, mostly because they think the vast majority of people are stupid, yes I’m looking at you Silicon Valley. These people are very rich and they are dangerous and they are influencing the political and social sphere. We have a lot to think about when it comes to what it is we really, really want to defend.

Zhou Enlai did not say “too soon to tell” about the French Revolution! There was a misunderstanding in translation, as there often is. He was commenting on the 1968 Paris uprisings.

? But this already covered by VJ above.

Woops! So he did.

Open Society ‘NGO’ (now Open Society Foundation) is a good example of ‘othering’ for nativist conservative right wing dog whistling and conspiracy theories, that also capture many of the ageing left*; of course nothing to do with being founded by Hungarian Jewish George Soros.

GOP pollsters and friends of Netanyahu’s, Finkelstein and Birnbaum (both Jewish) helped develop the Soros conspiracy for Hungary’s PM Orban and ruling party Fidesz. It’s clever in allowing a bob each way for ‘Christians’ as one can dog whistle Jews and/or Muslim migrants, and has now grown legs globally through alt right and white nationalist networks close to Trump etc..

In recent years Hungarians, through hollowed out govt. controlled media, have witnessed OSI and CEU being kicked out of Hungary, the Fudan University (it’s a good one) from China being set up in Hungary, paid for by the Hungarian government, plus Russian was invited set up their International Investment Bank in Budapest; Orban thumbing his nose at liberal democracy, open society and the EU.

There are some clear relationships, dynamics and shared targets, especially the EU, between Putin and many in the ‘west’ including fossil fuels, corrupting politics, derailing liberal democracy, Koch think tanks etc. in the Anglosphere of UK, US and Australia, at times far right in Italy & France, then Poland & Hungary sliding into ‘illiberal democracy’ flirting with exiting the EU (till about a week ago…), and then on the eastern fringes of the EU both Hungary & Russia have been supporting Bosnian Serb leader Dodik to derail EU accession.

Like a virtual or existential pincer movement on liberal democracy, with too many Anglosphere proponents, and with ageing demographics that are gamed for ‘collective narcissism’ and ‘pensioner populism’ to support charismatic leaders.

Even someone with your experience, VJ, cannot know for sure, but yes “it seems that people the world over want to live in democracies” and particularly and passionately in Eastern Europe.

About Ukraine, I find this persuasive:

“Zelensky’s Ukraine represents the hyperspecific and beautiful contradictions that stem from the acceptance of contradiction, the multiethnic tolerance, and the polyglot nationality of a thoroughly traumatized nation that just wants to exist, and to escape from the toxic bonds of world war and holocaust and gulag and famine that its revanchist neighbor has imposed on its population in the absence of its own ability to provide a normal life.” Vladislav Davidzon

https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/jewish-ukraine-fights-nazi-russia-zelensky

You know, this piece makes me think about the whole left-right paradigm in a new light.

As a life-long lefty progressive I’ve always (if I’m honest) defined myself by what I’m against rather than what I’m for. This is because, as a lefty, history hasn’t been all that kind to progressive politics. The right has been visiting outrage on our heads since WW2. Even the brief times when we were in the ascendant the right never let us have a proper go at setting a progressive agenda. Either that, or as soon as they got back in power, they tore down any sensible lefty policies enacted. All the left had, in the end, was frustrated rage. Hence, the left indulged in outraged screams for 50 years.

With the Ukraine, we have a simple cause to promote. Evidently a worldwide feeling too. Until this piece I wasn’t even aware what the political right-wing position was on Ukraine. I care even less what it is, but it is useful to know anyway. Rundle is right about our likely rallying around this nation because it is not too dissimilar from our own. If it were the Middle Eastern conflict, such as the Arab Spring, would we be as passionate about it. That happened, and the autocrats gutted it without much fanfare. A lot of “tut tuts” and not much else.

The Ukraine is not a great conflict for the left to get too confident about. It will probably end in tears. However, it still is a line in the sand, of sorts, and while it lasts, and however long that may be, it is nice to not give a dang what the right is doing and just promote certain principles on their own merits.

Here here.

There, there.

A cleansing tale from Guy always helps with dezombification

Cleansing?

Not the word I would have chosen – cathartic occasionally but mostly his pieces tend to be more senna than soma.

Not even Ayahuasca purgative, more Abbott’s aperient suppository of all wisdom, laxative in extremis.

Must be too many Bourbons with the latte.

Guy is one of an excruciatingly tiny number of journalists who tries to independently examine the complexities of events, and of this disturbing one in particular. For this he deserves accolades.

But I think is somewhat pointless to try to explain the Russia/Ukraine/NATO conflict in terms of political Right or Left. Communism is currently dead and almost all countries have capitalist economies and politics. The new capitalist Russia is fashioned entirely on ‘our’ principles of modus operandi.

Today Russia has a democratic system set up along ‘our’ principles (Currently there are 36 registered political parties, 6 of which have groups of MPs in the parliament, and the president is elected by universal vote every 6 years. The Russian president has powers akin to the US president.)

So what is the argument all about? Why has NATO been steadily moving its (and the USA also its own troops) up to the various Russian borders? Before Ukraine came onto the world scene, what exactly was the problem with Russia? Why, at the same time, wasn’t there any serious world push backs against the multiple USA wars of aggression, killing millions, razing countries to the ground and creating many, many millions of refugees?

In my humble view the argument is purely economic i.e. Russia is a vast land full of the most valuable riches. In 2003, the Russian government slammed the door shut on foreign companies buying up Russia’s natural resources and it started to ‘civilise’ the wild west style of Capitalism created by Yeltsin – a style that had ‘succeeded’ in transfering all the nation’s wealth into the hands of unsavoury and ciminal upstarts, and that had created homelessness, unemployment, and extreme ill health. At that point in 2003 Russia, overnight, stopped being the ‘West’s best friend’. The US oil company for which I was working threw a hissy fit and withdrew all its exploration projects. At that point Russia became the enemy.

It’s always about money and power. The idea of Russia becoming economically successfully and challenging the US oligarchs’ world domination was unthinkable.

Thus Cold War against Russia, mark 2, was born. It was bound to end up this way, in my view. The US has taken Ukraine and led it, like lambs, to an horrific and entirely unjustifiable slaughter. Good parents always advise their children not to play with fire…

Your writing today is more complex Mr Rundle, with thought-provoking ideas. I need a few minutes to digest every paragraph. For this I am thankful, and continue paying my subscription.

Yes indeed. GR drags us out of our comfort zones with thought-provoking ideas that require, even demand, further analysis and deeper reflection. Amongst so much sms sludge he is a very welcome stimulant.

Imagine if Bernie had won the last election, rather than Biden (yes, I know it was never going to happen, which is why I said ‘imagine’).

We’d now have a self-proclaimed US socialist standing up in Congress to castigate a Russian fascist. If that mental image is not enough to make your head explode (other than a thermobaric bomb) then I don’t know what is!

Maybe leading Congress in a rousing chorus of ‘The Internationale’. Long live the revolution!

The International Anthem of Socialism – YouTube

Bernie is a democratic socialist – is no diff between Finland, Sweden and other democratic socialist countries condemning Russian facism and Bernie condemning it. It’s ho hum of course he would condemn it rather than head exploding to me. What does democratic socialism mean to you??