Do economic sanctions work as a tool of foreign policy?

Opinions vary — often according to ideology. For example, business lobby groups like to explain that they don’t work because they cost their business donors money. Globalisation proponents dislike them because they prevent the free flow of goods, money and people to where the market dictates in the name of efficiency. And advocates for apartheid Israel, angered by the boycott, divestment, sanctions movement (BDS), like to insist sanctions have never worked anywhere, quietly ignoring the role they played in the end of the apartheid regime of South Africa.

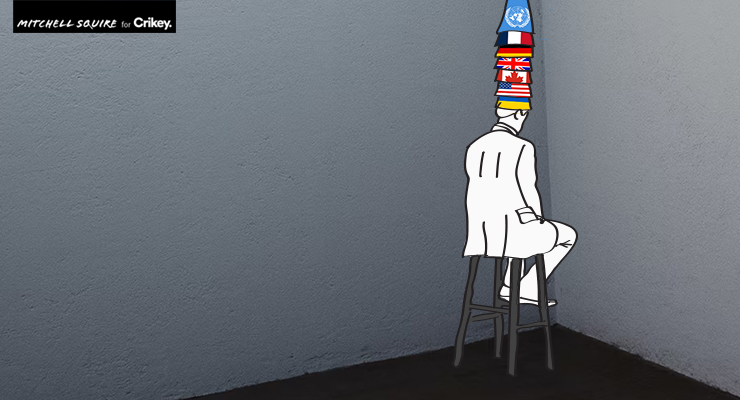

Others claim the sanctions deployed against Russia are a new and effective form of conflict, eliciting rapturous praise: “Warfare without the traditional war … potent, unified, cooperative and rapid action … What they did was just absolutely unprecedented in terms of the forcefulness …” And economist Steven Hamilton describes them as “devastating” for Russia.

But actual data is hard to come by on sanctions, despite their longevity as a tool of diplomacy — Napoleon imposed an economic blockade on England in the 1800s; Thomas Jefferson preferred severing economic relations to warfare as an instrument of statecraft, enabling the young United States to avoid a standing army and expansive navy.

But a timely literature review from June last year pulled together a large volume of data to assess the consequences of sanctions. While the Turkish authors of the study mainly drew methodological conclusions and identified data gaps, they also noted that, in terms of impact on GDP:

Comprehensive UN sanctions have a higher negative effect on targets’ GDP than UN sanctions in general. Similarly, multilateral UN sanctions tend to have stronger effects on the target’s GDP growth than unilateral US sanctions, while higher cooperation between the senders of multilateral sanctions is likely to increase targets’ costs. However, as EU sanctions are found to be less effective than those imposed by the UN…

Which is rather “no shit, Sherlock”, but now the data is there, and it points to why President Vladimir Putin is outraged by the wide-ranging sanctions slapped on Russia over the past two weeks: they build on existing sanctions; they impose significant costs across the Russian financial system and thus throughout the economy; they complement spontaneous action by many large Western corporations to sever ties with a regime suddenly too toxic even for them.

That is, on a scale between unilateral US sanctions and comprehensive UN sanctions (which, as the authors note, “devastated Iraq’s economy” as well as inflicted massive humanitarian casualties), the current Russian sanctions are closer to the severe end than the light end, and thus more likely to do damage.

What the study doesn’t quite come to grips with is the role of globalisation.

Sanctions in the 1980s may as well be Napoleon’s continental system. With the integration of global finance via digital transactions, the exposure of a target’s financial system is now substantially greater than in the analog era, especially when the dominant financial power, the US, wields disproportionate control of global finance.

Another theme that emerges from commentary in recent months about whether sanctions “work” or not is the repeated claim that they won’t stop Putin from invading Ukraine, or force him to pull back. But that is a straw person — no one has ever seriously said sanctions would send Russian forces fleeing from Ukraine. The aim instead is to demonstrate the costs of failing to comply with international law and the framework of international relations and to undermine the economic capacity of Russia to continue to prosecute the war.

Sanctions also convey the anger of the international community to Russians cut off from real information about what Putin is doing, and punish Russian elites who have enabled Putin’s lawbreaking.

There is also a moral issue. Few of us outside Ukraine — unless we’re willing to travel there and join an international brigade — have an opportunity to do anything about the crime being perpetrated by Putin. But sanctions — and going beyond sanctions to boycott everything Russian and to demand that others do too — gives us a way to express our disgust.

The question shouldn’t be whether sanctions work, but why any business-as-usual economic or financial relationship with Russia or Russians of any kind is justified.

And the lesson from the study is that the further sanctions move towards being comprehensive, the more damage they will do — in turn increasing the damage to Putin’s capacity to fund aggression in Ukraine or elsewhere.

US moves overnight to halt imports of Russian oil, and the growing refusal of Western oil companies to purchase from Russia, marks the next step towards more comprehensive sanctions and, hopefully, a more rapid transition towards renewable energy — although that will require alternative sources of palladium and platinum, where Russia has a major role (Australia may have a significant role there) — that leaves Russia’s fossil fuel-reliant economy stranded.

Australia could do its part by cutting off alumina to Russia, helping to choke off one of its major exports, aluminium (although Putin may be forced by sanctions to block exports, as he flagged today, in order to keep up domestic supplies).

To be successful, to “work”, the sanctions have to keep getting tighter and tighter, and extend further and further, with the goal of maximising the economic destruction of Putin’s Russia.

Keane should not conflate sanctions with blockades. They are both supposed to restrict the ability to move (some) things in or out of the affected country, but by definition a blockade is an act of war carried out by military force. Sanctions are not military actions and that’s the point of them.

When debating sanctions it’s worth noting JM Keynes in 1924 told the League of Nations sanctions are a poor tactic and it is better to give aid to the injured country than put sanctions on the aggressor. There’s a Guardian article about it: Keynes warned the world against using economic sanctions.

Prescient man, Lord Keynes. How awful for him, to try and avert WWII so early, to fail and to have no choice but to watch it unfold. Can you imagine how angry and despairing and impotent he felt?

Yes, sanctions and blockades are two entirely different things.A good example from relatively recent history.The United Kingdom maintained the blockade on Germany after the signing of the Armistice in November 1918 for another eighteen months and during that time one and a half German children died of malnutrition and lack of proper food and medicines.

Sorry, million.

“The aim instead is to demonstrate the costs of failing to comply with international law and the framework of international relations”

Don’t think so Bernard – let me fix this for you “The aim instead is to demonstrate the costs of failing to comply with international law and the framework of international relations if you are not the United States or one of its vassals and/or allies”

There, fixed.

Shorter would be more accurate – “The aim instead is to demonstrate the costs of failing to comply with the United States’ wishes“.

Looking forward to the sanctions imposed on those who destroyed Libya and Yemen. How can I do my part Bernie?

“The question shouldn’t be whether sanctions work, but why any business-as-usual economic or financial relationship with Russia or Russians of any kind is justified.”

Agree with the statement above – why continue to do business with a country – that invades a democracy because it wants to, threatens any country that will actively hinder that aggression with dire consequences and rattles the sabres of nuclear war. Such a country should be considered a pariah and ALL (government and business) connections severed.

What has the political system used in a country to do with whether it is OK to invade it? NOTHING. Just the usual White Western excuse. 1.6 Million killed the West in illegal wars by the West against Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria and Libya. The reason that non-Western Countries don’t overly believe in our Global Order is because it is set up to benefit the West, not all nations of the World equally.

The White West should be the ones sanctioned for their heinous and illegal acts across the globe. The US is the true pariah.

There is a lot of money in Russia to be spent, do you expect Macca’s to miss out.

Let’s call “sanctions” by their much older and far more accurate name – “siege”

The object is to starve the people until they get desperate enough to kill their leaders and throw their heads over the wall – “regime change”.

It used to work on cities. On countries? Not so much. Not without military intervention. Not without lots of starvation. Generations of it. Ask the Iraqis. Millions dead.

But go ahead and cheer for it being inflicted on a nation of people you’ve spent years telling me are under the thumb of a mad dictator. I can’t myself, because I’m pretty sure the Russians love their grandchildren, too.

Sanctions on Russia rally the people to support Russia. The west knows little about stoics.

Sanctions rally the people in all countries with a modicum of wealth, Tony. Look at Australians reactions to the sanctions China imposed on us.

Sorry, sorry – it’s sanctions when we do it but economic coercion when we’re on the receiving end.

China hasn’t really sanctioned us that much. There is something going on that we don’t know about yet. McDonalds is suspending its operations in Russia but is still going to pay the 65000 people who work for McDonalds, same with Coke. Pepsi have stopped Pepsi but will continue to supply all its other products. I don’t see those sanctions biting too hard. Do the powers think this is all short lived, I don’t know.

Yep, we got very light treatment from China- but remember the public outcry and flag waving? You’d have thought they bombed Sydney or something!

Australian sanction on China mean what exactly. Imagine China sanctions on Australia like they did with Lithuania, nothing accepted and nothing sent. There goes Bunnings, Office Works, Super Cheat, Total Tools and the list goes on and on. Is this what Dutton’s war with China means?

Dear oh dear. Our future would look a lot like the average Russians right now, wouldn’t it? But much, much faster- because Russia’s had years- decades- as a pariah state to prepare for this. We haven’t. We’d run out of everything yesterday.

The official LNP for Sanctions against Australia is “economic coercion” but not when it is the West doing the economic coercion.

Reckon you’ll find the distinction in all the Western playbooks, Lexus.

It fits under Hypocrisy – Western types of.

Of which there are so many. So very many. Enough to kill a brown dog. Enough to choke a horse. But mention ‘em and you get hit with the “whataboutist” stick. Really hard lately.

Western Society is very comfortable pointing out the faults of others, invading other nations etc but becomes very uncomfortable if anyone dares to point out the many, many, many faults of the West.