Who fills the food gap?

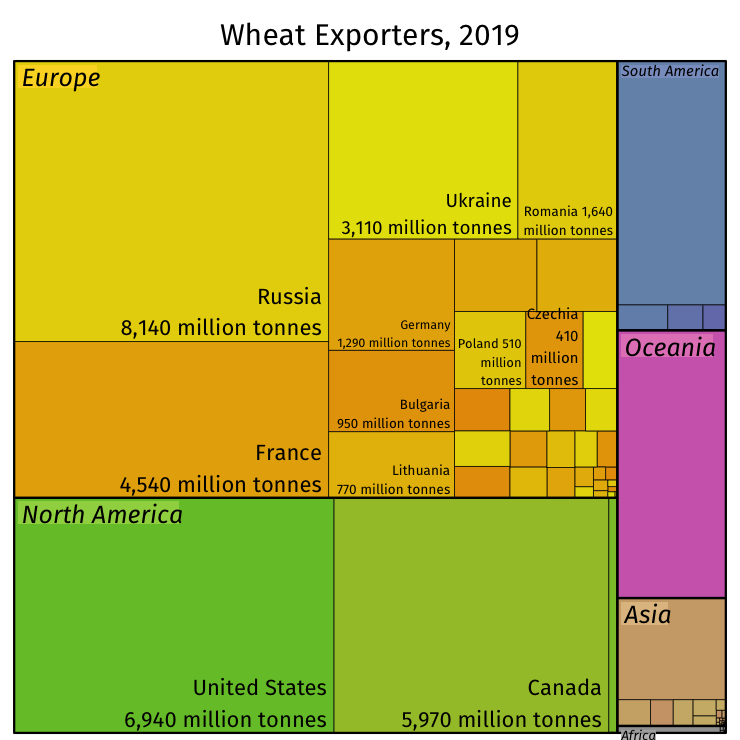

The world is about to enter into a food supply crisis. Russia and Ukraine make 30% of the world’s wheat, as this chart shows. Wheat accounts for about 20% of the world’s calories. How do we compensate for the lost supply?

Wheat is a winter crop. Australia’s wheat planting season is about to begin. Could we plant more? Our exports are the pink section in the right of the above graph, representing about 80% of the wheat Australia grows. Can we expand our exports? Can it be Australia that feeds the world?

Lines for bread

The price of wheat has soared, and it is important to remember what this means. It doesn’t mean everyone can get wheat but must pay more. No, when prices rise, it stops some people from buying.

That’s the whole point of rising prices — putting purchase out of reach of some and making others consider alternatives, until the amount demanded equals the amount supplied. Australians will reduce wheat consumption at the margin. But in the poorer parts of the world, higher prices are insurmountable. People will go hungry and die.

That’s awful. I started wondering if Australia could grow more wheat — golden crops waving in every paddock, right up to the edges of the cities, and right out to the desert. Is this realistic? I made some calls. The answer was good news… that is actually bad news.

Grainy reception

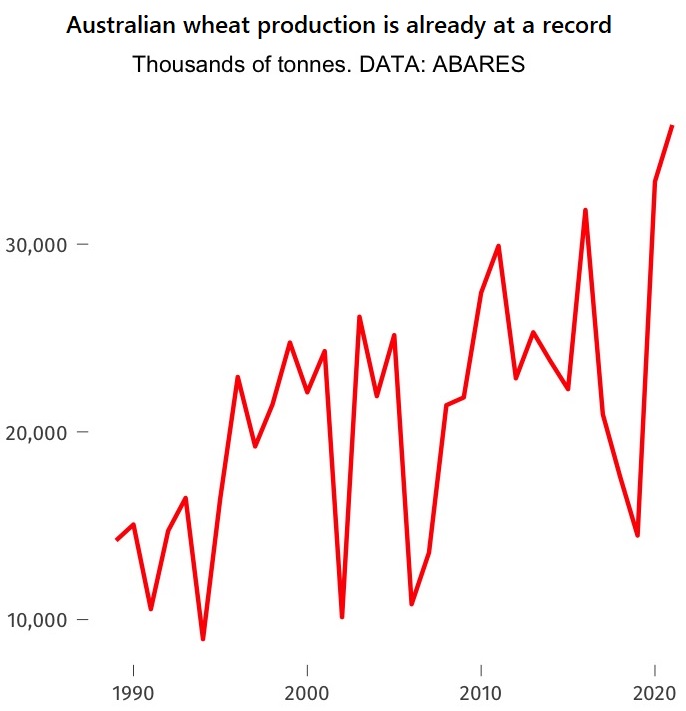

Australia’s wheat crop last year was a record high, with a near-record area of land planted and yields at their highest — each paddock produced more than ever before. The odds of us making even more this year are slight.

High prices help farmers sow with confidence, explains Pat O’Shannassy of Grain Traders Australia, but we don’t have a lot more room to expand.

“They are making planting decisions now so they will be looking to plant as much as they can with these high prices,” he said.

“We’ve seen an increase in cropping in the last 10, 15 years, but it starts to get maxed out and you start to end up looking at cropping in more marginal country. And these days with sustainability issues you probably wouldn’t.

“High prices and decent rainfall and we could produce a crop like we did last year, or we have a drought and we end up in trouble.”

Keeping the combine humming isn’t cheap

Fertiliser and fuel are impediments — they keep getting more expensive.

We grow a lot of wheat in Western Australia. WA farmer Barry Large grows plenty of it, and he is also the head of Grain Producers Australia. He is also worried about input costs that might make farming big crops of wheat less profitable.

“Before this crisis, prices for diesel, fertiliser and chemical were already at record high levels, but the continued escalation of these costs is heightening future production risks,” Large said.

“These costs are front and centre right now, with Australian grain producers making critical business decisions about their cropping programs ahead of planting the next crop in coming weeks.”

Elasticity is low

So who will respond to higher prices by producing more? We’ve seen the global economic system respond to challenges recently. The world can ramp up the supply of vaccines and rapid tests and masks. But ramping up supply of food, it turns out, is harder.

A recent study from Iowa State University showed that in the short run, food production doesn’t respond much to prices. If prices double, production of the most price-responsive crop — soybeans — goes up by just 20%. Wheat production goes up by just 3.5%. So it’s not just Australia that can’t ramp up food production on a whim. The earth turns slowly.

if we can’t increase production much, where can we find extra food to stave off famine? Stockpiles?

Like squirrels with nuts

The world keeps big grain stockpiles. Egypt has 4.5 months worth of domestic consumption on hand. India has a decent stockpile too after a lucky run of good seasons. But most of the world’s stockpiled grain — 142 million tonnes of the total 280 million tonnes — is behind one specific border: China’s. And it is not for sale.

What about corn destined for biofuels? Corn is a staple food that can substitute for wheat and in the US millions of bushels (each about 25kg) are sent to refineries to produce ethanol. The problem is that oil has gone up so massively in price and everything we can do to reduce consumption of oil — including adding extra ethanol to petrol — is a worthy goal right now.

Snouts in the trough

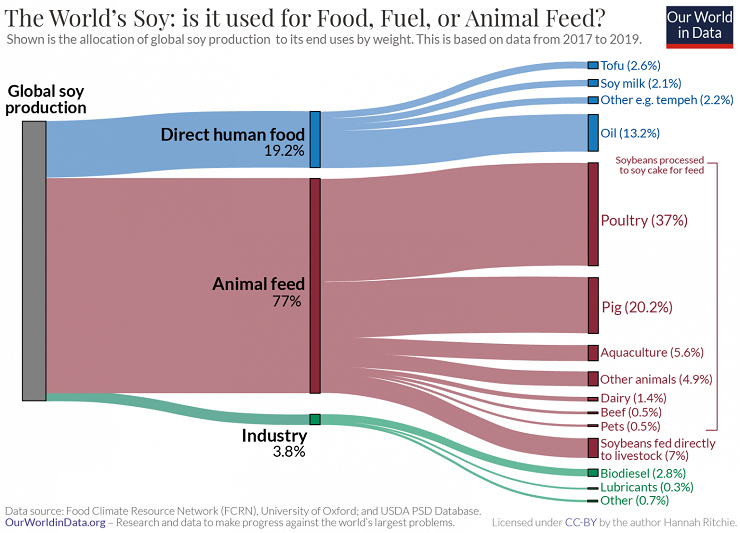

There is one other massive source of food — food destined for animals. Global agriculture eats itself. A big share of crops grown go to other farmers to feed animals.

Animals eat grains and beans of many kinds. In Australia animals eat three times as much grain as used to feed people, i.e. about 75% of domestic grain consumption is by farm animals. Reliable global data on what share of crop production is used as an input to animal rearing is not available for every crop, but for soy the figure is almost 80%.

This is a losing process. For every 100 calories you put into a cow, a person gets one calorie out in edible meat. For chickens we get 10 calories out for every 100 calories we put in. It would be far more efficient to divert those calories directly to humans.

Can we divert edible plants from animal mouths to human mouths? Yes, but it will reduce meat supply in the medium run.

If a farmer stops feeding an animal they sell it as meat. Every grain-fed cow and pig might end up with a shorter growing life and be on the meat counter a little sooner thanks to Vladimir Putin. This is called “destocking” and it is an emergency measure by farmers. The good side effect is it increases the supply of some meat just when we need it. Australian farmers did this in the drought — which was a similar circumstance of lower feed availability, albeit for grass-fed animals.

The consequence of destocking is lower supply of meat in a year or two, as the farmers let animals grow older and multiply, a process called restocking.

Globally, pigs are probably the big target. They don’t eat grass like cows. They compete with us for foods (albeit some of their feed inputs are not human quality.) But cows are an opportunity too.

In Australia, up to half of cattle eat grain in the final few months of their lives, a process designed to help them grow faster and get fatter. They enter a “feedlot” and eat barley, wheat and sorghum. The result is called grain-fed beef and is considered high-quality. It has been a booming market.

So if you want a bread roll to eat alongside your steak, it’s time to start eating grass-fed beef. And if you want Weetbix for breakfast the next morning, a sandwich for lunch too, and not to see ads on TV raising money for a famine in Yemen, it may be time to consider eating more tofu.

Have you changed your eating habits in response to world events? Would you? Let us know your thoughts by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

Jason, nice article. But check the graphic for “wheat exporters, 2019”. I think you will find the figures are US$, not tonnes.

According to the graphic Oz is irrelevant on volumes and has a massive guld to bridge when nations included are apparently exporting billions of tonnes?

Also, maybe a clear number for Oz would help too for comparison i.e. Australia accounts for about 3.5 per cent of annual global production’ and exports about 25 million tonnes p.a.

I presume Russia will now be selling its wheat to countries that are willing to pay in yuan. No doubt at a discount as well to the ridiculous world prices. What is not mentioned here is that Russia, China and Belarus produce around 50% of the worlds fertiliser which add another layer of complexity to the situation. One only needs to drive around our countryside to see most paddocks bare of grazing beasts. There is definitely more room for grass fed animals. Australian have been eating grass fed beef for 200 years. Grain feeding is only a recent introduction.

Or, like us, just eat less meat.. virtually stopped eating sheep and cow ….. only a bit of bacon.. a bit of chook and a bit of fish, that’s it, but commercial fishing is scouring the oceans so should stop that as well, ….and I grew up on a farm

An interesting article, which I wholeheartedly agree with, as a vegetarian.

But couldn’t a better, less Europe-centric graphic be found, one which actually states the amount of wheat we export? Surely it’s more than Czechia, which gets a precise figure.

My cows eat grass

The same tired argument for some level of vegetarianism. Although we probably don’t need as much meat as we do consume we are still omnivores. The ability to make tools (opposable thumb stuff) got our other digits on the really good stuff (marrow) and the human brain flourished – as one argument goes.

Anyone in this area of interest who hasn’t deep-dived into Regenerative Agriculture is wasting their own time. A bit down the track but de-desertifying the man-made deserts (all, except Antarctica) would add millions of hectares of arable land. ‘No cow shall live in poverty’ stuff, but it gets complicated. We actually need large herds trampling, slobbering, peeing and solid(er) wasting in a planned rotation to recover those lost lands, very Savory. Offering a good life for these animals followed by one bad day. Most traditional farmers are getting a small percentage of the dry mass that their land could produce and that will only improve when their allocation of rain stays, their microbes, worms, fungi and arthropods are too busy munching on each other to do other stuff, like steal the tractor. Furthermore any acre of agricultural land benefits from multi-species impact: e.g., a monoculture grain crop, followed by a herd of something eating the cover crop, followed by fowl tractors distributing the waste to get at the maggots, followed by a crimper and another monoculture crop and so on. But first the dirt has to be turned into soil and the ecosystem restored. For that he needs to learn about compost and compost teas and aerators and nozzle sizes and bioreactors and vermiculture and bird boxes. Fascinating stuff. The farmer will eventually learn to love his soil so much he never wants to see it again. Last one to sell his plough will have to accept scrap prices and pay to have it removed from his property. To be followed by a weeping and wailing Agri-business motorcade.

The politicians think we need more dams and Regen Ag wants to keep that water on their land where it has its uses.

The consumer can find out why food grown this way is better for them and their family (Dr Zach Bush) and get behind the early adopters to accelerate the transformation of dust and dirt to endless green.