The six-week campaign was always intended to help Scott Morrison grind down Anthony Albanese’s lead, but Labor might be hoping that instead it gives it the space to reset an already stumbling campaign and get Albanese fired up and on-point. The looming Easter break would help with that.

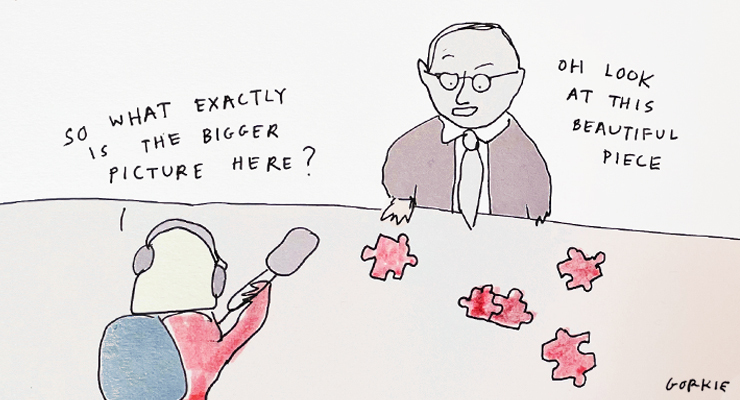

Regardless of “gotcha” questions, campaign gaffes and biased journalists, the Labor campaign’s primary problems so far are more fundamental. There is simply no coherent story around what it is offering, nothing that links its broader goals with its agenda for the next three years and longer — and its plans to implement that agenda. As one Labor figure said, we’re seeing jigsaw pieces without the puzzle.

This applies both at the micro and macro level. Take yesterday’s setpiece Medicare event, which also provided the platform for the launch of a relatively modest urgent care clinic trial. Labor can always get good mileage from warning of the need to protect Medicare from the pernicious clutches of the Coalition — Bill Shorten came close to winning in 2016 based on that — and Albanese could relax among the friendly environment of health staff.

But there are big-picture issues in health — workforce challenges, most particularly. We seem to forget that health and caring services is already easily the biggest employing industry sector in the country. Already more than one in seven workers — 2 million of us — work in healthcare, aged care or childcare. The health workforce by itself is the second biggest-employing single industry after retail. But hospitals and healthcare services continue to struggle to manage demand: regional health care in NSW is in crisis; the South Australian government lost the recent election there primarily because of hospital problems; much of Mark McGowan’s hermit kingdom strategy until February was dictated by the fact that the Western Australian health system has profound problems.

These are primarily state government issues, yes, but one’s health doesn’t always observe the rigid demarcations of primary and acute care. The lack of a coherent agenda more broadly for health makes additional spending on mental health or urgent care clinics look like, at best, bolt-ons to a flawed structure.

The problem is more acute at the macro level. Not since the 1990s recession has Australia needed some clear, coherent thinking — about the aftermath of the pandemic and the changes it has wrought; about the urgent need for far more ambitious climate action; about our relationship with China and our failing efforts to somehow bar China from our region; about the impacts of what at the moment seems like an extended war in Ukraine; about the tragedy of aged care. Each of these on their own would be enough for an election campaign, but we face them all at once, along with trivial problems like a long-term budget deficit created by our permanently larger government.

Albanese and Labor should be offering a narrative around these issues, one founded in Labor values, that links values with vision with plans, something that the campaign can fall back on no matter what idiot questions journalists ask. Labor has to give voters a reason to come to them, by showing it has a serious vision, by offering a compelling story.

It doesn’t matter that Morrison is offering nothing of the sort. Morrison doesn’t do vision, by his own admission. But voters know what they get with Morrison. They’ve had three years of it. He’s just promising more of the same. It might be corruption, incompetence, shallowness and inaction, but for some that’s good enough. Labor has to offer more than announcements. If that’s what voters want, they’ll stick with Morrison. That’s all he does.

Yes. After Labor’s campaign stumbled in 2019 and the election was lost there was much said about the many policies Labor put forward. They did not seem to add up to a coherent whole or a proper vision. Voters could not see the wood for the trees. The lesson Labor took from that was to cut down the trees. Now there are almost none left but voters still cannot see the wood. Of course not. There is no wood left.

There seems to be a Labor/Labour tradition of “let’s never do that again” – it’s the same in the UK possibly because the ALP and UK Labour share the same consultants – both are trying the small target strategy (exactly as Beazley did so successfully /sarcasm)

Yeah. You could hardly miss old Kim.

Its a baby and bathwater response

Just because you lost partially because you had too many policies doesnt mean you’ll win with *no* policies.

I’m sick of the B/S excuse that Labor had too many policies in 2019.

The problem was that Shorten et al were incapable of arguing for them and just mouthed the words fed to them each morning by handlers.

Presumably because they didn’t believe in them and thought them a result of coked up wonks writing what focus groups wanted.

AFAIR each of the policies was generally popular enough whenever the public was asked. So yes, it does look like a failure of presentation (in the face of the hostility from Coalition, media and Palmer) did the damage and so scrapping the policies is a really stupid self-defeating way of addressing the problem. But that’s Labor.

It is self-defeating and also unnecessary as policies weren’t the cause of Labor’s loss imo. 2019 was a replay of the 2016 US election. The LNP emulated Trump’s tactics (which mirror Russian propaganda tactics) in degree I wrote to Aus Civil Liberties in the lead up expressing concern that we were on a slippery slope to fascism. My stomach knotted at every utterance of ‘retiree tax’ as I understood the public were being programmed to believe there was one, and as with the US election the media, and oft unwittingly, promulgated the lies – are number of studies of times Hilary’s emails etc were mentioned on mainstream sites like CNN and NYT compared with her policies + overall media time greatly favoring Trump and while not studied here to my knowledge it was my perception that similar was occurring here. Did people vote for Trump because of his policies or to stop crooked Hilary etc etc?. Did people here vote for policies or to avoid a retiree tax or save their utes and weekends etc? At the best of times many do not vote rationally – I recall reading some voted for Kennedy as they liked his hair – and the presence of dysinformation campaigns is the worst of the times as it is rank mind control. I spent election praying my perceptions were wrong and if right that Labor could eek a victory regardless. The parallels with the US 2016 election were so stark it amazes me so many were surprised.

Actually I heard Shorten speak very well on many occasions, answering questions well too. He wasn’t ‘mouthing words’. He knew his direction and details.

If you heard him at the GetLabor RC droning on & on when asked a question you would not think that.

He could, up to a point, repeat lines learned by rote – with the familiar problem when doing that of pseudo asphasia, mangling words/syllables like Spoonerisms – but when they ran out he scuttled away because he was incapable of expressing a spontaneous thought.

For the simple reason, like the current ‘leader’, of never having had one.

The Coalition won 2019 with no policies.

Some might say that is because it exemplifies the average voter – no wucking forries, I’m OK at this moment, don’t bother me with thoughts for the consequences for the future, if any.

Most Australians do not appreciate democracy. Compulsory voting contributes to this as does the wealth of the country.

The number of functionally illiterate people in Australia is remarkable. According to the OECD, 40%–50% of adults in have literacy levels below the international standard required for participation in work. For a wealthy country, this is a disgrace. The question then is why are people so disinterested in becoming more literate? Perhaps they are spoilt. They never really had to do it tough. Critical thinking is beyond them. that is why we get saddled with mediocre governments. Australia is dominated by mediocre people.

I have office bearing responsibilities in a small community volunteer organisation. I admit I have been very surprised by the low literacy level and these are of people in the boomer plus era when rote learning and phonics were the predominate teaching methodology. I c@n see a push backwards by our State Government to this failure of outcome

That’s a bit unfair. For a start, Morrison clearly promised to set up a federal integrity commission if his party won.

Press 3 for more options, press 9 to return to the main menu.

who’s pressing 3?

Is an election really the right time to release something as contentious as policy?

the Greens have struck gold with ‘billionaire tax’.

what’s labor got?

A carton of Liberal lite and some goon, both heavily taxed.

I hope Anthony Hu is preparing to bond with the cross bench to form government or operate as a minority government. The question is how many votes is the Freedom mob going to scalp from the TPP primary vote? I’d run a book on it going below 75% for the first time ever, seismic shift, if I cared.

You’d think Labor would be pivot the battle around wage growth, especially in the health sector, and pull out the the ol ‘cost-of-living’ grab bag of micro and already-slated reforms to control the narrative by putting the LNP on the merry go round spinning around, never able to fix a target.

Unfortunately the strategy seems to be “vote for us because we are less s#!t than the Coalition”.

To be fair, it did kind of work here in South Australia.

That has been their ‘strategy’ (and I use that term very advisedly!) since the days of Hawke and Keating. In fact, I can recall Hawke gloating that ALP members had nowhere else to go as he (Hawke) proceeded to turn the party into a pale imitation of the Liberal-National Party.

Many went to the Greens. Some have regretted it.

Actually that was Wotevs Richo, a Moloch consigliere since 1996.

If not earlier, which is highly probable.

Not that pallid either.

Worked for Biden…

Bidet’s Build Back Better worked for Biden. The Democrats abandoned it as soon as they got in. The electorate will abandon them accordingly- watch and see. And they may not come back again. The Democrats have pulled this on the American people too often.

Two Dinos won’t pass critical legislation through the senate.

Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema are Murdoch stooges looking for a Fox Noise gig and have promised to block any ‘progressive’ legislation.

America is a democracy in branding only; gerrymandering, redistricting and selective anti-voting methods are a Republican speciality.

As a democracy it’s a basket case.

No they did not abandon it, although there was constant obstruction and dilution due to GOP, and disappeared by media…

Yes, because apparently once in power he was supposed to surprise everyone and implement progressive policies, save the world etc. Or so Democratic voters thought. Same now here in Australia. I’m told by Labor voters that Labor can’t risk telling us during the campaign that they’ll fix Australia. But they’ll do that for sure – I mean fix it – once they’ve won the election. Welfare recipients, environmentalists, the sick and disabled, refugees needn’t worry – all will be good. And the Coalition won’t screech that Labor won based on a lie and besides – debt and deficit, so how will they pay for that?

In the US there are two so called Democrats in the Senate blocking many of Biden’s proposals.

Same as the Liberals pay for all their big spending, borrow. If the LMP were not such a corrupt government and spend billions on private consultants who give them they answer the want to hear, they could save a lot of money, but instead they borrow. Despite being told to have a claw back clause in jobkeeper, they preferred to hand millions to business did not quality, as covid generated huge profits for them. They borrow money to support their donors, hand out grants to anyone they like or will benefit them. They use taxpayers’ money, as if it was their own. and have taken the art of pork barrelling to a new level. It would save a lot of money and would be far more affective.

In case this wasn’t clear I was just pointing out that the Coalition would rediscover ‘debt & deficit’ and worry sick about it should Labor want to fix the country once in government.

As I said at the time, all Biden and the Democrats achieved in 2020 was a dead cat bounce. Electing Biden hasn’t ‘worked’ in any way that matters. Trump and all his 75 million or so supporters still say Biden stole the election. Even having scraped home with control of both houses of Congress (just) and Biden as President the Democrats are almost completely paralysed, their legislation fails to pass, the investigations of Trump and the coup are going nowhere except for small fry and the Republicans are continuing their sedition. The half-terms will restore Republican control of the Congress and the Republicans, having learned the lessons of their narrowly failed coup, will return to full control of the country in 2024 by whatever means it takes. Voting will never remove them again.

Actually trump recently admitted that he’s lost the election.

It’s not quite that simple, is it? In that interview he talked about foreign leaders were happy that he had lost the election; but he still describes it as rigged and he still sees Biden as an illegitimate President. So he was only admitting that Biden really has stolen the Presidency. Sanity has not broken out, normal service has not been restored.

“Sanity has not broken out, normal service has not been restored.”

no, I didn’t claim that. Only that the words have passed his lips which I found an interesting development.

That was purely a reactive concession when, during an interview with one of the crazies who now orbit around him.

His interlocutor had pointed out that the Constitution prohibits a 3rd term – ergo, he could not claim to have won in 2020 and still run again in 2024 which was the theme of the interview.

Meaningless, mumbo jumbo from the orange ogre – like Scummo, he lies to suit the perceived need of the moment, without heed or care for any relationship to before or after, let alone veracity or reality. .

That seems to be the strategy. But after all we’ve been through in the last three years I suspect that voters would be open to an honest politician who has some genuine beliefs and was prepared to take some flack for them. Examples might include saying that tax cuts for high income earners isn’t a great idea right now, welfare payments below the poverty line are unacceptable, and that that keeping asylum seekers in detention for years is indefensible.

Shocked&Awed, I would have thought the same. However, after reading Bernard’s article and how most people have responded, it seems that honesty and caring for the electorate does not count. That building back the public service, fixing the age care system and making it easier for women to go to work, does not count. Even having a infostructure plan that will benefit everyone, such as building public housing, having a better climate change vison (they can’t be to bold, or they will spook the media and the LNP) Intending to bring back workers right, all this and other items that were mentioned in Albanese’s budget reply, seems to be of no importance or as being seen as different to what the LNP promises. Poor country Australia

GoTo, This is the first sensible comment to this article. Labor does have a vision, to fix the broken care and education models – starting with aged care and early childhood education, something that is taken for granted as being available in an affordable fashion in France where I am living at the moment. We are not well served by our media, sadly including Crikey, who refuse to give Labor any credit for their policies, already announced. Not to mention FICAC, and a large new investment in renewable energy. I have only just resubscribed to Crikey after droppong in in 2019 because of its relentless anti-labor position, and total lack of interest in who Scott Morrison was, and what he would do if elected.

It looks as though Crikey subscribers are now a bunch of rabid same-same types, who figure that voting Coalition is fine.

And it worked for the opposition at the last election. Two slogans, I am not Shorten and Back in Black (which was a not true) but as we have learned in the last three years, lying is normal for this MP. And that is quite acceptable. Abbott’s only vision was Axe the Tax. Even Turnbull had no vison. But Labour always must have a fully funded, detailed plan and a vison for the country. However, the moment Labor gives any details, the media, including Bernard takes it apart. As long as we have in this country only the choice of two parties and the media we have, the democracy will go further and further down the drain. Well, lots of people keep saying that Australia is the US 51 State – maybe they are right

And they can’t even manage that

“It doesn’t matter that Morrison is offering nothing of the sort. Morrison doesn’t do vision, by his own admission.”

The fact that the media in this country only ever ask one side “what is your vision?” indicates is bias.

If it doesn’t matter than Morrison offers no vision, then it should not matter that the ALP doesn’t.

“But voters know what they get with Morrison. ”

A lazy, do nothing liar?

“If it doesn’t matter than Morrison offers no vision, then it should not matter that the ALP doesn’t.”

You’re right, but you also know that that’s not how politics and media work in this country, right? Be it higher expectations people have of Labor or be it plain malice but the ALP is held to a different, higher standard than the Coalition. Pity they don’t live up to that standard.

Yes, I do know that is how politics and media work in this country. It appears to me to be getting worse.

Ideally the question of vision would be put to both, that both have to explain policy in detail.

As it is, it will be the second election Morrison will go to without any substantial policy, and I don’t recall if Turnbull had any in 2016. In 2013 the policy was to undo what Rudd/Gillard had done.

Absolutely, and even if the LNP does not offer policy details, the media will neither demand nor evaluate past policy/portfolio performance, for themselves vs. personality politics and ‘he said, she said’ gossip.

Part of the problem with critical policy issues in Australia is due to our media oligopoly avoiding good analysis while lacking aggregating the same on all policy areas.

Meanwhile Australians have become conditioned by legacy media to look after themselves, their hip pockets and ‘amuse themselves to death’ (Neil Postman) with sport and light entertainment.

I think this is the main point of this total beat-up. I’m waiting for the MSM (mordoch will never do it, but at least 9 and the ABC should) be everyday reminding us of Morrison’s venality adn lying and corruption. I reckon that’s the biggest isssue – apart from Climate change, of course. Sure Albo was hapless and should do much better, but I think there is much better chance of honesty and policies for the poelpe (all Australia). certainly an upbhill battle for Labor with Murdoch and Costello taking every opportunity to divert the agenda from policy and focusing on gotchas . .

Exactly! Sick of LABOR bashing, 10 yrs of SH!T / NO POLICY AGENDA but great at dishing out BILLIONS in TAXPAYER funds to SCUMMO/LIBTURD/NATIONAL corporate parasites, why we have TRILLION DOLLARS and rising in DEBT! People don’t need to be told what will be on offer from SCUMMO the pathological LIAR we’ve experienced for the 3 yrs and 7 yrs before that under COAL-ition! So all Anthony has to do is hold his nerve, be clear about what their policies are about, Aged Care nurses, MEDICARE retained, real JOBS, not the ones SCUMMO has promised for the last 3 yrs and 10 yrs of LIBTURDS! And the fanciful unemployment numbers, is only low because those fulltime jobs have been turned into casualised 1 hr a week jobs and lack of visa holders! We know who SCUMMO is, he’s a lying, self serving, back stabbing, smearing, bully boy, with no empathy, or compassion or nous!..”Mr Morrison’s poor character, which is supported by amongst other matters his long history of lying to us, and it goes to the very heart of the reason why Mr Morrison is unfit to lead this country, indeed unfit for him to be elected as Prime Minister at the 2022 Federal Election. We of course have seen or read in the news the stories about the leaked text messages, whether it was Barnaby Joyce as I referred to in Part 1 yesterday, or Gladys Berejiklian, which describe Mr Morrison as a liar, a complete psychopath, and a horrible, horrible person. These are texts sent by Mr Morrison’s own party or Coalition partner.”..then there is his IncompetenceThen there is the issue of competency regarding this shambolic Morrison Government. I have already raised my views regarding the Morrison Government’s poor handling of the pandemic. In addition, we have seen so many scandals ending with the hashtag ‘gate’, there wouldn’t be enough paddocks in Australia with gates to match the hashtags. Some readers may jump up and down saying I’m being too soft to call these numerous ‘gates’ acts of incompetency, but until a Federal ICAC is established, and until a court of law says otherwise, I can only personally say the word incompetency. I have set out in detail in my previous articles published by the good people at the Australian Independent Media Network (The AIMN) the Morrison Government’s incompetency!” He’s being promoted by MERDE-dick with many free kicks along with the rest of the msm spineless journos, trying on gotcha questions to try and trip up ALBO! Only the brain-dead sheeple will continue to believe the BS!

I could not agree with you more, but it seems that most people that have responded to Bernard’s article, prefer that style of our current government. Apart from what you mentioned above, no one seems to care how under the cloak of national security and lack of transparency our privacy laws and our rights are getting destroyed. More and more laws have come into force that in Western European countries would be considered as overreach. Further, our so-called independent agencies are getting stacked with LNP symmetrizers. Australia no longer has a health functioning democracy and if this current government is getting re-elected, Australia’s democracy will get lost even further and will look more like that of Hungary.

Well spoken sir. I like the line about the gates & paddocks. If you don’t mind I’ll pinch it.

Tend to agree BK. Previously, it was a good idea that while the LNP was destroying itself, don’t get in the way. But now is the time people have to think what’s on offer and Labor have to put forward an alternative. I realise that campaigns should be structured to be effective over the six weeks or so, but come on, NOW

The problem with having a vision-in Australian politics-is that News Corpse is more than happy to twist and distort that vision into a Nightmare…..just to ensure their Librorts Party mates remain in office. They did it during the Rudd-Gillard years, and have been doing it all through Labor’s time in Opposition. If vision was the key to winning Australian elections, then the Coalition would be permanently in opposition.

Exactly, the modus operandi while claiming to be ‘fair and balanced’…..

The things BK is asking for, I don’t remember anyone ever asking the Libs to produce them, coherent vision blah blah and all that. Ever. So they’re things not needed in a Liberal or National government, but essential for the Labor party to get into government. Is Australian politics now ruled entirely by this massive double standard? And as you say, Marcus, were the Labor party to produce the coherent vision and the rest of it, News Corpse would belt the bejesus out of them, with Nine and the other corporate ratbags following along, including the ABC. The present government is a stinking carcass that has to be buried and yet we get angst and anger over Labor’s lack of vision. I don’t like it either, the shrunken policy pitch, but what hope have they got when the government’s critics demand the same thing from Labor as its enemies?

Well said, Cap’n.

Yes.