You’re at after-work drinks one Friday evening when an inebriated colleague lets slip how much they earn. Some of your workmates’ cheeks flush with embarrassment for making so much more than the poor sod; others bite their tongues to suppress their rage at being so comparatively undervalued. Someone changes the topic.

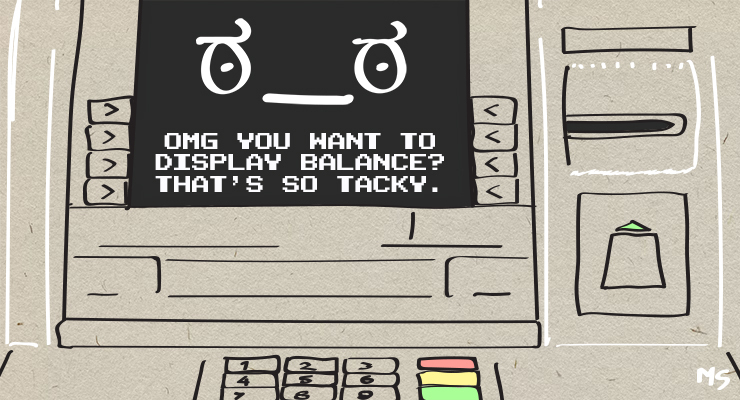

It’s long been taboo for employees to discuss their salaries frankly. But in my view such discussions shouldn’t be awkward aberrations. We must normalise them.

The silent status quo serves our bosses nicely. It leaves unjustified discrepancies unquestioned — including gender and racial disparities — and leaves workers stabbing in the dark when asking for a raise with no benchmark for what’s possible.

The silence has grown especially deafening in Australia. As Alison Pennington from the Centre for Future Work told Smart Company: “Australia stands out internationally for pay secrecy practices,” including clauses in employment contracts that ban workers from talking about pay, something that’s illegal in some countries.

Could things be changing?

Earlier this year the Commonwealth Bank and Westpac removed pay secrecy clauses from their employment contracts after a Commonwealth Bank employee was controversially fired, partly due to “discussing confidential remuneration with colleagues”.

A fortnight ago, consulting giant PwC went further, announcing plans to publish its pay bands, allowing workers to see approximately how much their colleagues and bosses are making. The bands are not exact reflections of the firm’s payroll, just approximate benchmarks.

And on Tuesday, consulting rival Accenture Australia followed PwC by publicly disclosing details about its staff pay and equity options, although it provided less detail. The Australian Financial Review reports that Deloitte and KPMG plan to disclose their pay rates in coming months, leaving EY the only “big five” consulting firm keeping its remuneration largely secret.

Such moves in the finance and consulting sectors, which have some of Australia’s highest gender pay gaps, are welcome. But they remain optional, and many firms continue to closely guard their payroll secrets.

We’re still a long way behind

Overseas, however, governments are looking to make transparency mandatory.

From May 15, New York City will require companies to publish minimum and maximum starting pay with all job ads. Vague lines about the salary being “commensurate with experience” (read: we’ll see just how low we can lowball you) will be a thing of the past.

Business associations are desperately trying to have the bill repealed, suggesting it will prevent them from discreetly offering candidates from marginalised groups higher salaries to meet diversity targets. It’s an astonishing argument, given opaque pay scales more plausibly facilitate discrimination.

In March, California’s Senate began considering a bill that would require employers to disclose their average hourly rate for each job category and for key demographics, including race and gender. And US companies that have government contracts are already prohibited from retaliating against workers who discuss their pay under an Obama administration executive order.

The EU is considering a similar directive. It would also ban recruiter questions about pay history and “expectation”, Pennington says, and “reproduce intra-firm gender pay gaps”. The proposal is partly inspired by Iceland’s world-leading system introduced in 2018, which bans non-disclosure clauses, makes pay scales transparent, and requires firms to prove they impose no gender disparities for equal work — or else they incur a daily fine.

Albanese could follow suit

If Labor wins the election, Australians could find it easier to discuss their pay with colleagues. Last year Labor leader Anthony Albanese promised to prohibit pay secrecy clauses if he becomes prime minister. The Greens introduced a bill to do so in 2016.

Conversely, Industrial Relations Minister Michaelia Cash’s office has said that “the inclusion of pay secrecy clauses in employment contracts is a matter for the contracting parties”, adding that scrapping them could “undermine the ability of organisations to manage workplace performance”.

In a campaign replete with vague and unconvincing proclamations about lifting stagnant wages, pay transparency laws represent a real point of difference between the parties.

Would it work?

Studies consistently show pay transparency reduces the gender pay gap by as much as 50%. Bosses stop undervaluing their female staff and giving back-slapping bonuses to the blokes when they know they’re being scrutinised. There is also evidence that it reduces overall inequality between workers.

But it doesn’t always increase overall wages. Sometimes it does, with angry employees successfully negotiating to receive the same as their higher-paid colleagues. But sometimes bosses even things up by merely reducing bonuses to high-flying employees, typically men.

To increase both equity and overall wages, research shows transparency measures must be coupled with collective bargaining through unions. A tight labour market also helps.

So Labor’s proposal would be likely to benefit women and create a more equal economy, but until the party gets serious about reforming the Fair Work Act to allow multi-employer bargaining — which it hosed down late last year — overall wages are likely to remain low compared with company profits.

Until we see political leadership, change must start small.

Next time you’re at knock-off drinks with your colleagues, push through the taboo and tell them how much you earn. It might just help them in their next salary review.

There is a lot more to this than meets the eye. In the days when Awards were more influential there was no where near as much secrecy. Part of getting rid of simple Awards was to confuse the issue and allow the boss’s mates to be paid more.

When in business (I was no saint and retired over a decade ago) I was the lowest paid employee. Each employee was given access to the balance sheets associated with their Division and paid a negotiated bonus accordingly. In addition each employee was paid the full 12% Super Guarantee Levy from the original proposed date over a decade ago.

Small/medium business owners do not need the cash income as much as employees as there are numerous benefits that flow to the employer. If other owners and managers are not benefiting in this way they are just plain dumb and should not be in business.

When I sold I walked away happy and have not wanted since. My employees rewarded me handsomely by making my Company a valuable asset.

We should seriously look at legislation for employee representatives to be on the Board of Directors. Surprisingly they often know more about what is going on in the business than the Owner/Manager.

Exactly, says much about Australia when award system has been disappeared from media narratives, to normalise individual contracts, using the Americanism and asking ‘your boss for a raise’; think Germany has union reps on company boards.

Basic HR101 or management, why? Because lack of transparency can lead to sudden workplace disruption and resignations when personnel learn that a colleague is paid more for the same or less (can be gut wrenching); hardly induces teamwork and cooperation when working age has passed the ‘demographic sweetspot’.

If it flowed through to the top, it could lead to senior executives and CEOs getting such crazy amounts of money, bonuses etc.- ultimately beneficial to stop this horrifying trend towards greater and greater inequity.

Reminds me of a celebrated incident in the late 1940s (a bit before my time admittedly) when a bunch of insurance company workers in Cape Town went back to the office after a session at the local pub and shot open the locked filing cabinet containing the branch’s salary records – using a service revolver belonging to one of returned servicemen involved.

Those were the days ….

Ahhh Memories.

I was told (i.e. hearsay) that in Switzerland, everyone’s tax return is open to public scrutiny.