I’ve been writing opinion pieces for Australian media corporations like Fairfax, the ABC and now Private Media for close to 25 years. But — newsflash! — I’m not a journalist.

Instead, I’m one of the few experts left on the media scene since the great disruption caused by the internet destroyed the traditional media’s income stream, the traditional media jobs that stream funded, and the line traditional media drew between news and opinion.

Back then, commercial and editorial were kept separate, as were journalists who reported on facts, and opinion writers — mostly external experts — who commented on the news.

Why did such lines matter? Because they offered structural impediments to bias and, by so doing, preserved the trust readers had that the facts being reported were true. This loss joins social media-induced hyperpolarisation as a significant cause of the erosion of trust now threatening the survival of liberal democracies.

But I digress. Here I want to talk about what happened when experts — scholars, cultural and business leaders, or economists — left the media scene around 2011-12 and were replaced by journalists moving seamlessly from reporting the facts on climate change, interest rate rises or changes to Medicare to commentating on these developments in their own news organ or that of a competitor. Think ABC TV’s Insiders and Slate’s Political Gabfest.

But journalists aren’t experts. Experts are people who live and breathe one subject area for their entire careers, or at least the time it takes to do a doctoral dissertation. In contrast, journalists are generalists, which means they know a little about a lot of things but not a whole lot about much.

Except politics. For most journalists, politics is the daily water in which they swim. Their business is news, and they know how the news game works, how it can be subverted by talking points and spin, and how their competitors are playing it.

Which explains how, in the swap from subject experts to journalists, we began hearing more on the political game and less in-depth analysis of the issues that shape our future as Australians and our individual lives.

Ah, for the good old days, when the reporting of each election announcement would be followed by expert dissection of what was included and missing, and whether it hit the mark in terms of solving the designated problem.

Sure, I loved the five minutes a day spent listening to Michelle Grattan elucidate the government’s messaging, decode the opposition’s spin and tell me how it would “play” — but in the same way you love frosting. It’s good in small amounts, but too much makes you sick and is beside the point.

So here’s my wish for the next three weeks of the campaign: that serious news outlets rejig their election coverage to include in-depth expert commentary that explains the detail of what each candidate proposes to do and whether it will succeed.

Each day, highlight an individual or party that could win a seat and summarise their philosophy, objectives and key policies, and get a subject matter expert to analyse them. Does the policy align with the values? Can it be implemented, and will it work as described? What will be the consequences — and for who — if it fails? Would another way of dealing with the issues be better?

Right now is the most attentive many Australians will be for the next three years to discussions of how our MPs have represented us, and what they will do if we anoint them for another stint. Right now, we’re all ears. Use the time wisely.

Before the money went out of newspapers, the better ones actually did have journalists who had some expertise in particular fields and so could make informed commentary. Now there is not even reporting, yet alone evaluation of the election policy platforms of the various parties/independents

Leslie C, great article, question is, how do you rid the current ‘media-induced hyperpolarisation’, by journalist of Australian mainstream media?

There needs to be a complete overhaul of the Australian media, to ensure:

That the’standards’ of old, that you refer to in your article – are reestablished and upheld re: ethical reporting of the truth and facts

Think in the US they call it ‘horse race’ journalism, aka NYU Professor Jay Rosen? In other words focused upon niche hollowed out issues, sound bites, repetition, popularity and/or approval ratings i.e. who’s ahead or winning; precludes any deep or broad analysis.

Maybe we should call it “copy and paste” press release publishing

Sorry to disappoint you Leslie but the likes of you have disappeared never to return in Australian media.

A young woman I know who is busy studying for her doctorate in macro economics is so disappointed in her Australian university that she is looking overseas to continue her studies.

Why? Because the university is not interested in macro economics because it does not make them money! Universities in Australia are now just a money making exercise and not at all interested in in-depth studies of how the actual world works. All they want to do is churn out engineers, doctors and Andy other degree that can make them money.

Thank you Leslie Cannold, for giving us an explanation for the current frustrating media election coverage. It was very helpful.

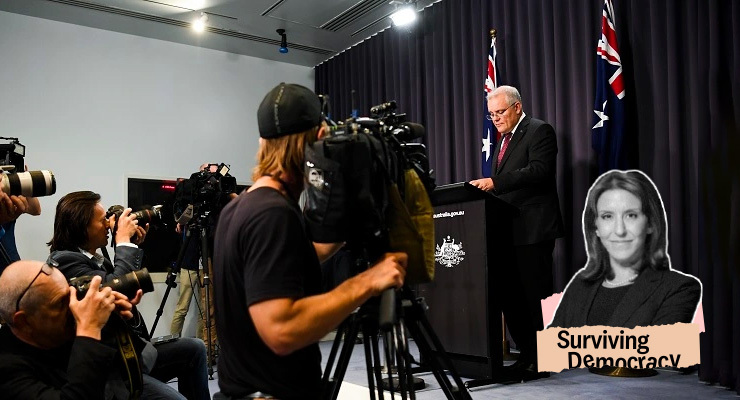

i despair at the inane comments from journalists on what a “strong campaigner” Morrison is. Just because he is a good liar, can gaslight and spin, does not mean he is being effective. The media seem to me to be dictating the terms of the campaign; your explanation that in the past, politics was reported by journalists, and followed up with analysis by experts, makes sense.

How do we change the discussion to integrity and policies instead of tricky and cunning politics???