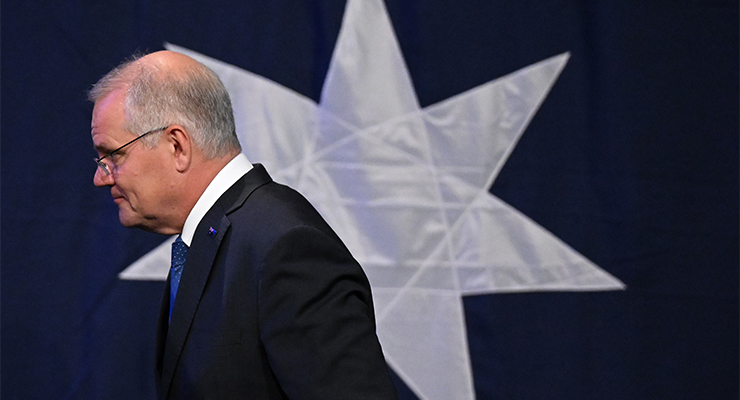

Scott Morrison was not merely Australia’s worst prime minister, he’s the worst prime minister for his own party on either side of politics.

No leader has presided over the gutting of his own party in the way Morrison has. Some have lost their own seats. Some have suffered landslide defeats. But none has ever neatly cut the heart out of their own party base and sacrificed it to their own egos, factional interests and ideological obsessions.

The election result has destroyed the myth, endlessly peddled by the press gallery, that Morrison is some sort of political genius. It turns out he got lucky in 2019 against an opponent in Bill Shorten who served him up a bain-marie of possible scare campaigns. Faced with an opponent less inclined to spend an election campaign with a bright-red target on his back, Morrison struggled. Only his opponent’s stumbles kept him in the game.

Throughout the campaign, Morrison stuck doggedly to the playbook crafted across multiple elections in Australia, the US and the UK by right-wing apparatchiks: relentless demonisation of your opponent (whether Labor or independent), micro-targeted pork-barrelling, culture wars and intense coordination with News Corp and tame journalists. In doing so, he sealed the fate of more moderate MPs based in seats that have been the party’s heartland since the formation of the Liberal Party.

His strategy of deliberately running a divisive transphobe in Warringah (having effectively prevented far more suitable competitive candidates from seeking preselection) was central to the culture war campaign he hoped would deliver him the votes of social conservatives in outer metropolitan seats.

It failed miserably — what’s remarkable about the campaign is that the Coalition vote did not shift in the polls at all. Morrison was able to drag Labor’s vote down, maybe enough to cost it majority government — but he couldn’t budge the dial on the overall level of Coalition support.

In the end, all it did was undermine the chances of sitting MPs like Dave Sharma, Trent Zimmerman and Jason Falinski.

Those MPs, along with Josh Frydenberg in Kooyong and Tim Wilson in Goldstein, were already starting at a profound disadvantage against independents due to Morrison’s climate denialism and obsession with backing fossil fuels, as well as his stolid refusal to accept a federal anti-corruption body. Indeed Morrison made those totemic issues in his campaign: any actual climate action was a “sneaky carbon tax”; a federal ICAC would be a “kangaroo court”.

In doing so, he simply made a tough campaign even tougher for those MPs.

There’s a pattern here, of course. Morrison looks to have gone out of his way to damage the chances of MPs more moderate than himself, leaving them to be overwhelmed by the oncoming teal wave while Morrison smirked his way through outer suburban and regional seats, moving from one glib non-announcement to another.

The result is a political party that has moved dramatically to the right, with an array of more moderate MPs no longer in politics and the party left in the hands of Peter Dutton. The Nationals, who have yet to lose a seat despite a small overall swing against them, must be unable to believe their luck: the Liberals have moved closer to them.

So Morrison leaves with a key goal of his centre-right NSW faction achieved: the smashing of NSW Liberal moderates. That will be even more the case when Marise Payne announces — probably sooner rather than later — that she’s retiring.

In politics, your real enemies are always behind you, not across the chamber from you, but Morrison has been happy to inflict a dramatic defeat on his own party as the price for pushing the Liberals to the right and inflicting a savage strike on his factional enemies.

It’s a rare achievement, to be that bad a prime minister, that bad a campaigner — and that bad a leader of your own troops.

I think the low Labor vote is more nuanced than Morrison’s “anti” campaign being entirely responsible. The rise of Greens tells us that.Labor misread the room when they tip toed around climate action. My hope is that Labor has less fear and more conviction in their governance than they did in their campaign.

The ALP was avoiding being wedged on anything though.

Standing for nothing means being walked over, if lucky, or kicked to the gutter if not.

Did anyone say that the Labor Party stood for nothing?

Albanese?

Only on small, irrelevant things such as principles, vision, values and integrity.

“Only on small, irrelevant things such as principles, vision,values and integrity.”

To quote John McEnroe “you cannot be serious!” Look what abandoning those small irrelevant things did for the Liberals. The ALP in Opposition would only have had to blink on most of the COALition policies to be very publicly eviscerated far and wide.

Well, obviously you haven’t read the labor party platform.

If you maintain your previous assertion, then how did Scummo win the ’19 election ?

Oh, I don’t know. Perhaps a $90 million campaign of lies, smear and disinformation by the bloated billionaire in exchange for a no questions asked approval for a massive coal mine next to Adani. Remember the 40% death tax?

Just lucky I guess, or did his god person arrange it?

The Teal seats still would not have voted Labor. They have to be taught to vote for others before they could possibly cross the aisle properly. This result is perfect. A Labor government with a beating conscience – a teal/green conscience. Democracy itself was the winner on the day. Scomo is a fraud.

Nice one, Albo.

I think traditional Liberal voters, were happy to trust the quality of the Teal candidates. Many voters would have found the jump across to vote labour was a step to far. The Teals Rock.

Absolutely correct. I live in Curtin and was more than happy to vote for the Independent rather than “waste” my vote on the Labor candidate. As did a number of my friends. Anything to rid us of that obnoxious ScoMo. And it seems to have worked.

After the Shorten experience, Albo was petrified to suffer the same fate. The narrow, at times seeming ineffectual, line seems to have got him in. Step one. Now he is there, I hope he is much more confidently progressive

That remains to be seen, but his time as the manager of relationships with the independents during the Gillard govt will help him here. He knows how to manage the relationships with principled people. That and some understanding of just how strong the national mood for climate change reform is key.

Exactly. Revealing their policies would have led to Scum being reelected. They couldn’t lay a finger on Labor this time and it worked.

Nearly everyone I talked to, realising that their votes would end up with Labor, used their preferences to vote for greens and green leaning independants. This was in the hope that it would send a strong message to the Labor Party that their climate change targets were NOT aspirational enough. With an extra hope that they would be forced to negotiate with a greens/teal balance of power.

Even my dyed-in-the-wool Liberal voter mum couldn’t stomach the thought of her vote showing any support for a party lead by the disgrace that is Scomo. She voted Green.

Agree. But the fear was that less than tip toeing might help Morrison’s strategy in their heartland seats. The actual result now justifies them going much further on climate change policy. Minority government would give them the excuse to go much harder, even with majority the success of Teals and Greens still provides justification, an even greater majority supporting the reform on the floor of parliament.

Labor in minority government will be able to negotiate well about Climate change.

Thank you Australia.

Wonderful. Why not merge the leftover govt rump into the Nationals, and finally rid ourselves of the most mis-named political party of all – the Liberals

The primary vote story being thrashed by the gallery is a bit of an insult to voters’ intelligence. Voters realise we have a preferential system and exploit the power it gives them. If they vote Green first and Labor ahead of the tories, or an independent ahead of one of the major parties they know what they are doing. To only quote first preference support for Labor and thereby ignore the clear intentions of many voters is dishonest and condescending to the millions who have expressed their will in creating this parliament.

Yes, that is a perennial fault of journalists of all hues. They seem to think that the voters are some brain dead amorphous mass that turn up and have to puzzle out the voting papers every election. I think Australians have shown time and time again how well they understand preferential voting, and the role of the Senate. I remember well hearing Michelle Grattan one time on radio referring to ‘out there in voter land’, and thinking how very contemptious that term was.

Yes, the MSM hacks treat elections as a sporting contest between two antagonists. They have no idea that we’re voting for a representative parliament.

A big thank you to Bernard and the Crikey team over the last few years for exposing the numerous deficiencies of the Morrison government while in office that were not always reported by the MSM. It was definitely not a good government that had lost its way. It was a bad government that became ever more appalling.

Yes I wonder what the MSM will do now. They must be bereft and rudderless . . . I am so delighted the concerted evil campaign both Murdoch and Costello conducted didnt win in the end.