Australia’s media have a tricky question to work through: when will Anthony Albanese have become sufficiently prime ministerial to be prime minister?

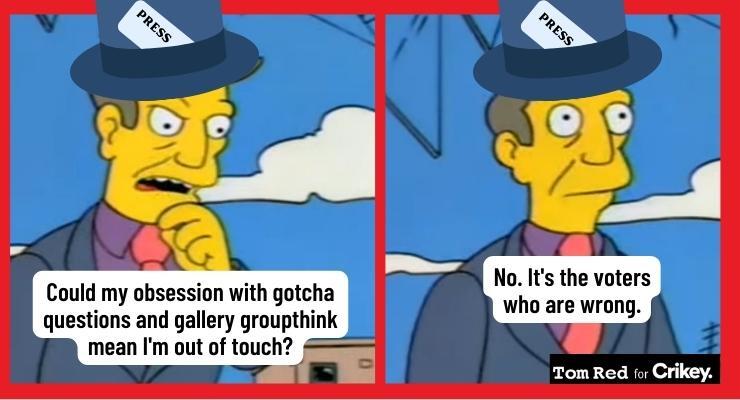

That could be some time, judging by the press gallery’s continuing sense of bewilderment at just how the election ended up as it did.

For Albanese it’s an urgent political imperative. It drives the narrative of first-term governments — Labor governments more than most. It determines whether they’ll get a second term.

News Corp is already screaming for an all-caps “1000 days of resistance” and at that rate it doesn’t leave much space for a pivot to Labor legitimacy before, say, Valentine’s Day 2025. No surprise. That’s its business model. But based on Fox’s Joe Biden-bashing in the US, it’s set to be far uglier than anything Australians have been used to or are likely to accept.

The rest of the news media need to move on. More important will be the ABC — yet so far it’s struggling. Partly it’s the inevitable stumbles caused by the whiplash from going from one government to the next. For example, its generally successful election night broadcast gave significantly more space to still-Senator Simon Birmingham’s “record low primary vote” than it did to the soon-to-be minister Tanya Plibersek’s “a win is a win”.

Its reporting on Albanese’s first big prime ministerial moment — his participation in the Quad meeting and reshaping of the communique to recognise the climate emergency — was part relief at a gaffe-free performance leavened with amazement that he was there at all.

Time (and pressure from social media) will moderate its tone. The value of each party’s contacts will be repriced. The currency of access journalism — the background briefings out of the PM’s office — will already be from Labor staffers, not Liberals.

But it will take more than a tonal shift for Albanese to get the imprimatur of “prime ministerial” across the press gallery. Reporters have spent the past three years persuaded (or being convinced by those affable leakers from the PMO) that, nice guy as he may be, Albanese isn’t up to it. Even now that the election has punctured that foolishness, expect it to continue to flavour both reporting and think pieces. The gallery loses its convictions slowly — before it does suddenly.

The past 40-odd years of Australian politics has set the gallery up as hard judges. Bob Hawke is probably the last PM to get the prime ministerial stamp from day one. As in all things, Hawke is the exception that proves the rule. Some PMs never get there. What with eating raw onions and dishing out knighthoods, even Tony Abbott’s parliamentary colleagues recognised within two years that, sure, he was a great opposition leader, but prime ministerial? Not so much.

Other leaders seized on events, like Paul Keating with the Mabo decision and his Redfern Park speech or John Howard with gun reform (and later, to the long-term detriment of Australian political life, with Tampa).

It took Scott Morrison 18 months and a global pandemic to become prime ministerial, delayed by his initial deliberate positioning as opposition leader to the Shorten government and then a self-indulgent back-half of 2019 culminating in his ultimately career-destroying Hawaiian holiday.

Bizarrely, having climbed back through his Team Australia management of national cabinet in 2020, he threw it away in 2021 with politicised attacks on the Labor premiers of Victoria, Queensland and Western Australia, neatly turned back on him by Albanese with his “two jobs” failures over vaccination and quarantine.

Labor has attempted to set course for a Hawke-style legitimation since Albanese returned from his COVID-enforced isolation. Party strategists seem to have learnt an important lesson from the first week’s gaffe: the mistake was giving the media a win by apologising. That, they seemed to think, made the press pack hungry for more.

Instead Albanese ditched small target rhetoric for talk of “legacy”. He repositioned the travelling pack as the enemy of “orderly government”. From Saturday night, he turned the electorate’s embrace of a new politics against the pack’s suddenly out-of-date shouty-ness.

He turned the fragmentation of the two-party system into a victory for change. He’s aiming for prime ministerial by delivering on the big demands that the electorate has served up to the political class: integrity through an anti-corruption body; reconciliation through the Uluru Statement from the Heart; serious action on climate; an embrace of diversity and an end to culture wars.

It’s taking the gallery a while to catch on. But these issues, sooner rather than later, offer Prime Minister Albanese the route to prime ministerial legitimacy.

Journalists – some young, some old – lazily rusted on to repackaging government talking points – will take time to adjust to Australia’s new political landscape – and perhaps even longer to recover from the shock that, despite their very best efforts, Albo’s team – plus the Greens and the Teals – found greater than imaginable electoral success on Saturday last, delivered by voters who very largely ignored these journalists’ streams of drivelling inconsequential chatter.

The contrast with the French media’s treatment of France’s recent polls is instructive. Newspaper reports place significant gravitas on the policy differences which emerge between candidates during the progress of the election campaigns. And night after night leading up to the polls French television programs give hours to discussions between competing candidates seated around the same table. Having watched these for several elections now I find these contributions highly illuminating. In the days before the final poll there is a long debate between the two finalists – Macron and LePen for the past two elections – and under the rules of the debate, each candidate has the opportunity to reflect on assertions made by the other about their candidacy. There is often really good to-and-fro in the discussion. It’s great television, and great for informing the electorate about what is on offer in policy terms – and also in terms of the intellectual and political agility of each candidate in dealing with questions raised during discussion.

In Australia we see none of this. The ‘debates’ on commercial television were lamentably light-on in terms of policy considerations, and in the print and radio media, the focus on ‘gotcha’ was simply too facile to count as a serious contribution to the discussion of issues cogent to a federal election.

A Royal Commission into our media, covering ownership and content and balance and consumer satisfaction would serve our country well.

In October 2000 I was in San Francisco watching political programs on TV. I thought then how lucky the Americans were in having such civilised debate about the policies of GW Bush and Al Gore. How things have changed.

“More important will be the ABC . . . ” The only player that can contest Murdock. But more importantly, the only media entity ‘owned’ by we Australians. A small resuscitation required at moment, but retrievable.

I think Albanese has a notion of leadership which is often associated with women ( and therefore often overlooked), not out here as a macho, chest-beating ‘I am’, but a more slowly slowly cabinet-style consultative approach which can often be more effective in actually getting things done and taking people with you. This will confound the journos who want big announcements and constant noise and movement.

News corpse has proven itself to be pretty irrelevant. Even Clive (Mr Titanic) Palmer’s $100 mil investment only got him one dude into parliament.

If you go for a train trip it’s very hard to ever see a ‘paper’ newspaper – with it iron curtain paywall – the so called ‘Australian’ is very hard to access; thank god for that. With its plethora of advertising, and premium for HD, Foxtel is no bargain either. Tech savvy young people (and BB’s like me) have better ways to spend their time and future.

PS: more people should watch question time and other free events, courtesy of live parliamentary broadcasting – it’s fun to catch a peak at sleeping MP’s working hard or trying to ‘hear hear’.

“News corpse has proven itself to be pretty irrelevant.”

No it hasn’t. You are not seeing the bigger picture. News Corp has shaped the whole political landscape. The result of this election is not what it wanted, but the result in 2019 killed off any ambition Labor had for any substantial moves in several vitally important areas. This time Labor has a programme that includes cutting taxes for the wealthy and doing nothing that might rein in rising house prices. There is no reason to think Labor will have much effect on growing economic inequality. Labor’s limited vision and pathetic timidity is to a large extent a News Corp victory. This would be a very different Labor government if News Corp had not broken Labor’s spirit long ago. Labor remains terrified of News Corp.

So you wanted the LNP liars in again. Have you read the ALP policies. Thought not!

What the F are you on about? These ALP policies you refer to make the case for News Corp’s continuing influence better than anything I could make up. The lack of any serious ambition to combat global warming. The tax policies favouring the wealthy. The bipartisan lock-step on domestic surveillance and restricting civil liberties. Housing policies that feed demand and so push up prices, enriching the sellers at the expense of the buyers. The lack of any proposals to restore trade unions’ standing. And so on. All not quite so bad as the Coalition, but still on the same page. So News Corp should feel very satisfied with its work, even if it failed to save the Coalition this time.

Yes SSR, butLabor had to get elected first. I sincerely hope the priorities you list do start to be implemented. I think the interpretation that Newscorpse has had an truly negative effect on political aspiration is a sound one.

To have “…read the ALP policies.” would require a powerful microscope and very strong stomach.

They may have successfully restricted Labor’s ambitions, but that only gave rise to more Greens and independents, something I think New Corpse would now be much more worried about. It’s hard to herd an ever increasing number of cats.

Yes. I don’t think Labor knows what to do with Murdoch, unless they have secret plans to legislate to break him (and Stokes in WA) up on national security grounds. Labor are still shell-shocked from the 2019 result. Still, I think we have to acknowledge that to be re-elected (and they HAD to be re-elected… who else was going to save Australia?) they had to eschew, or pretend for the time-being to eschew, certain positions on certain matters. Now they’re in, they can move, but first they have to learn how to speak to the nation; to articulate their position; to state their case. Shorten (and the rest of Labor) fell way short of this in 2019.

Exactly. And that’s why News Corp is still anything but irrelevant. From it’s point of view the wrong party is in government, but it’s still a party that has been shaped by News Corp intimidation, its lack of ambition is a News Corp victory and its lack of a clear majority despite the many gross failings of the last government is also something News Corp can congratulate itself for.

And the Murdochs are still pretty effective at getting the other MSM (including the eunuchs at the ABC) to self-censor by blindly following the daily agenda set by the Murdochs’ dominance of the morning newspapers.

Between the rabid Murdoch political party and a thoroughly cowed ABC, that’s the rural mining electorates pretty much sewn up and that’s where much if not most of the rage is. And it’s only going to get worse over the next three years. They will go all out to reverse this election and ensure the people never get uppity enough to attempt its like again by deliberately tearing the country apart. They won’t care how they do it, either. If it means convincing their miner mates letting go of a few dollars now and letting coal collapse overnight will be good for business because it will destroy regions and the right will own them forever more, so be it. Plenty more holes to dig. Big mining boom coming from renewables anyway.

The media has proven to be largely irrelevant, although too few of them realise. it yet and those that do, won’t admit it. The exception my be Sky After Dark idiots whose prescription for the reform of the coalition is political suicide. I say leave them to that important work in the national interest.

I note we have not been showered in talk of ‘mandate’, that concept that has long been dishonestly wielded in a system where the ‘winner’ of the election gets 33% of first preference votes. But what happened on Saturday was that a genuine mandate was delivered by the electorate: Labor’s anaemic aspiration but massively enlarged by the agendas of The Greens and the independents. Labor has a mandate to double its aspiration and get really stuck in while the coalition and News Corpse have painted themselves irrelevant.