The Abbott-Turnbull-Morrison governments were big on what it means to be Australian, which they demonstrated mainly by removing rights we’ve tended to assume that, as Australians, we hold.

The High Court has not been a bulwark of protection for those rights, mainly because — as it so often points out — they mostly don’t exist.

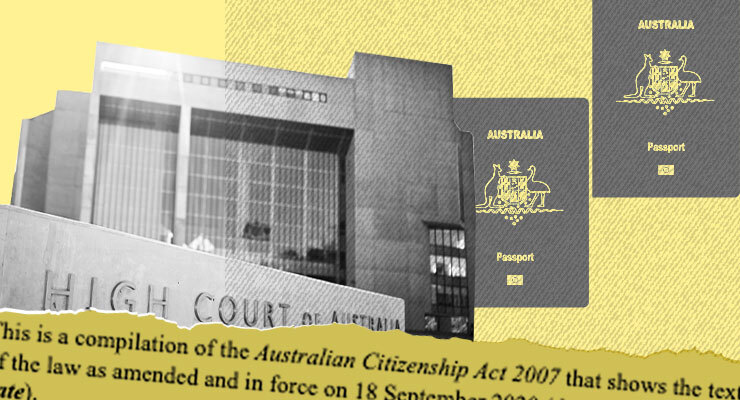

However, every now and then the top court pushes back, which it has thankfully done by a comforting six-to-one majority in a decision of major importance: whether the Australian government can declare that an Australian citizen has lost their citizenship by acting in a way that demonstrates repudiation of their allegiance to Australia.

The answer is no.

The relevant law is section 36B of the Australian Citizenship Act, inserted in its current form in 2020. The act sets out a number of ways in which an Australian citizen can lose citizenship, including voluntarily or, in this case, unintentionally.

It’s most easily explained by the facts of this case. Delil Alexander was born in Australia in 1986, becoming a citizen automatically. Because his parents were Turkish immigrants, he also acquired Turkish citizenship by descent.

In 2013, Alexander travelled to Turkey and then on to Syria, where according to ASIO he joined the Islamic State and was “likely engaged” in activities of foreign incursion and recruitment for terrorism. He was eventually captured by Kurdish militia, handed to Syrian authorities and imprisoned. He remains detained in a Syrian prison, apparently indefinitely.

Alexander’s passport was cancelled and a ministerial order made preventing him from entering Australia. In 2021, ASIO handed a security assessment on Alexander to the immigration minister. Under section 36B, the minister then “determined” that he had ceased to be an Australian citizen, on the basis that he had engaged in foreign incursions, which demonstrated a repudiation of his allegiance to Australia.

The ministerial power is engaged when the minister makes these factual findings: that the person has done something that is on a list of very bad things (including foreign incursion); that such actions demonstrate repudiation of their allegiance; that it would be contrary to the public interest for them to remain a citizen; that they wouldn’t be rendered stateless if their citizenship ceased (that is, they have dual citizenship).

It’s a lot of facts for a minister to find. The act says the minister doesn’t have to give reasons, and that the rules of natural justice don’t apply. Judge, jury, executioner?

Well, yes, said the High Court. Alexander’s lawyers challenged the minister’s decision on the ground that section 36B is entirely invalid because it offends the constitution. They put it two ways: it was outside the Parliament’s constitutional power to make this law at all; or it offends the constitutional principle that the power to adjudge and punish criminal conduct.

The first ground failed, the court ruling unanimously that the “aliens” power in the constitution gives the federal Parliament the ability to determine when a person ceases to be a citizen. So that’s the end of that argument, which has been floating around for years (disappointing, I think, but there’s no point arguing with the entire High Court bench).

The second ground is quite tricky. It’s old law that the constitution seeks to preserve the separation of powers between the judicial and executive arms of government, by exclusively reserving to the courts certain functions. Any attempt by the executive, or by Parliament to allow the executive, to step on the courts’ turf will be invalid.

The basic principle here is that the function of deciding whether a person is guilty of a crime, and imposing punishment for it, is one that can only be carried out by a court of law. That is promised so as to ensure that the full protections of our criminal law — the presumption of innocence, natural justice, prosecutorial burden of proof — are preserved and nobody can face punishment by arbitrary or capricious determination of the executive.

It’s not that simple, however, because over the years the High Court has allowed a lot of mission creep from the executive at the lower levels of criminal culpability. For example, police can give you an on-the-spot fine for lots of minor offences. The Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) can disqualify a person from being a company director, and many other regulatory agencies have powers to fine or otherwise punish miscreants.

Where the dividing line is, nobody really knows, which is why the government defended section 36B’s validity on the basis that it’s really no worse than ASIC’s disqualification power. It also said that losing one’s citizenship isn’t really a punishment at all.

The court was not buying that. It pointed out that citizenship includes rights. It is “an assurance that [its holder] is entitled to be at liberty in this country and to return to it as a safe haven in need. These entitlements are not matters of private concern; they are matters of public rights of ‘fundamental importance’ to the relationship between the individual and the Commonwealth.”

Wow. I wish it had said that before we tried to overturn the India ban in 2020. Would’ve helped.

Losing your citizenship, the majority said, is analogous to the ancient punishments of exile or banishment. And those were always regarded as punishment, not merely an administrative act whose purpose is to protect the public, as the government was arguing.

The principal purpose of section 36B, the court found, is “retribution for conduct deemed to be so reprehensible as to be incompatible with the shared values of the Australian community”. That’s consistent with what the act says and with the arguments the government has constantly advanced to justify its desire to strip people of their citizenship. It would be disingenuous to pretend that all the “unAustralian” rhetoric we’ve been bathed in for the past decade wasn’t about punishing those who fall short of the dictated standards.

It’s just that that punishment, so far as section 36B is concerned, is by exclusion. It is banishment, nothing less, and it is punitive. And that is the exclusive turf of the courts.

So chalk one up for the good, because one of the thousands of rights-denying “national security” laws passed in the past two decades has fallen, and a little bit of due process has been restored.

What a shame someone can’t put the same successful effort into getting Julian Assange back here.

Sure is/has been…though the disgraceful bipartisan failure on Assange’s basic citizenly rights of our last five parliaments, over a full decade, will be thrown into urgent relief by this decision, and especially any subsequent material return home of Alexander. So it just might give Dreyfus & Co a bit of a hurry-on.

I am glad of this decision. I was always uneasy about Dutton giving himself broad powers to decide when someone was being unAustralian and trashing the security of citizenship for dual nationals.

It is in the same vein as his attitude to criminal deportation – two people commit a crime together. Both are equally guilty. Both serve the sentence for their crime but the one who is a citizen gets to stay whereas the one who is a permanent resident (and has lived in -Australia since childhood and thought s/he was a citizen) gets deported for a not necessarily serious crime.

It is one man deciding for Australia what it means to be Australian and giving himself extremely broad powers to decide who is not, without any kind of public debate on the topic.

A good summary of a crucial decision marking a welcome red line in what has been shifting sand since 9/11. If a partisan, merely transient parliamentary majority can summarily erase any citizen’s civic essence like this then concepts like collective sovereignity cease to have any meaning, too. Which in turn renders the entire country ‘un-Australian’. Being ‘Australian’ basically becomes contingent for everyone. We all become civic non-entities, in a neo-terra nullius of our own making. Which might raise a wry First Nations smile, I suppose.

Too true but far too arcane an concept for most readers here.

It’s concerning enough that someone like Assange can be effectively rendered a ‘civil dead’ by dint of parliamentary expediency. The idea that our entire civic existence could be permanently erased by same is an even more egregiously antithetical trashing of the separation of powers than, say, effectively declaring someone guilty of rape by multipartisan parliamentary declaration.

We are living in a time of radically extrajudicial, anti-democratic regression. Osama bin Laden really, truly did a job on our civilised self-confidence and progressive liberal surefootedness, huh.

As OBL predicted re the US reaction, we did it to ourselves.

Jack – I have long thought that the impact of Osama bin Ladin’s attacks was mainly to make target countries try to be as tribal and oppressive as Saudi Arabia, his home country. It’s ironic and galling but probably not surprising.

I’m not against the possibility that some actions are deserving of stripping citizenship, but it seems to me that power should never be in the hands of politicians or anyone else who can wield it as a political weapon.

Hardly surprising when we have had a generation of bipartisan imported US policies, tactics and dog whistling of refugees, immigrants and identity; would never occur to the powers that be to apply same rigid rules on Anglo-Irish ‘Australians’ but if deemed to be ‘immigrant’ (even if 3rd generation), it’s different?

Politicians should not be allowed anywhere near these decisions as it seems more about dog whistling and denigration vs. taking ownership and responsibility for all citizens and residents.