As the RBA turns the screws on Australia, hoping to suppress purchasing activity and thereby reduce inflation, mortgage repayments are rising. Borrowers are the treadle on which the foot of monetary policy bounces out its rhythm, up and down and back again.

Are households with mortgages suffering? Two-thirds are at least a little bit ahead on their repayments. Others are having hard conversations about what to do as mortgage payments rise: whether to work more, perhaps labouring over the weekend instead of spending time with family — or cutting back on expensive groceries.

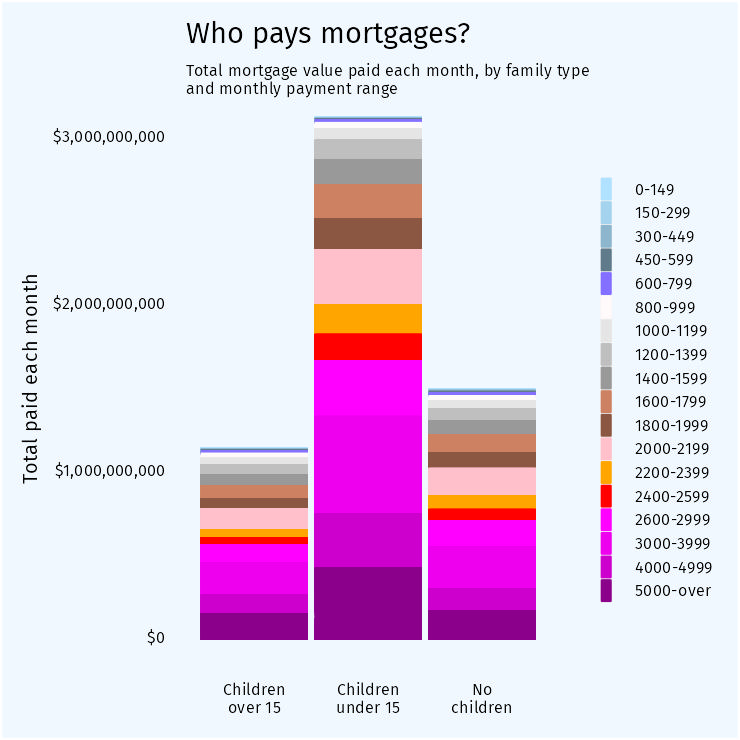

Different families face different choices. Mortgage-holder households matter, not just because there are so many of them, but also because so many of them have kids. As the machine of monetary policy makes households tighten their belts, kids get squeezed. As the next chart shows, $3 billion was paid each month by mortgagee households with kids under 15 at the time of the census in 2021. A lot more than $3 billion will be flowing from households to banks now official cash rates have risen from 0.1% to 1.35%.

The chart above illustrates that some people have significant mortgages. There’s a chunk of people paying off five grand a month or more and far more paying more than $2500 a month.

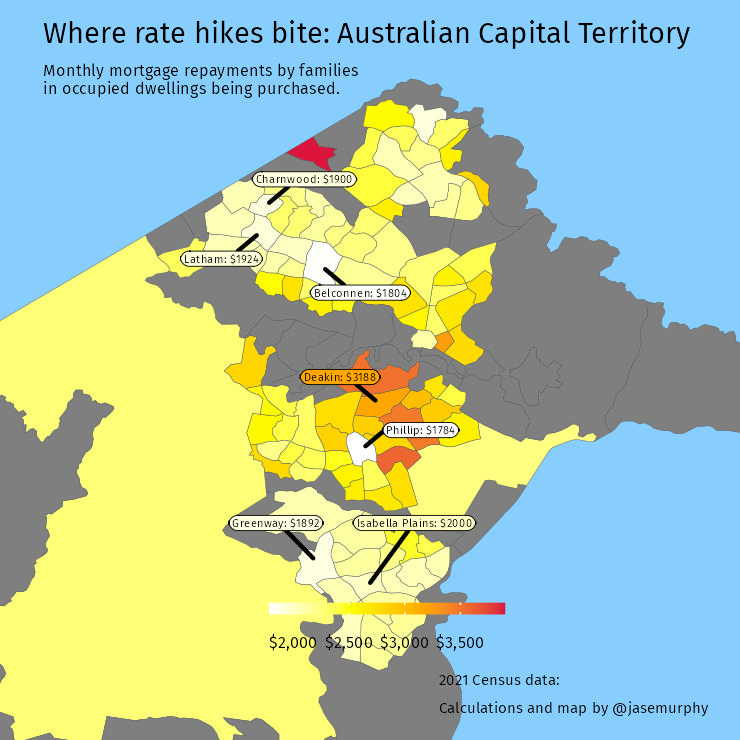

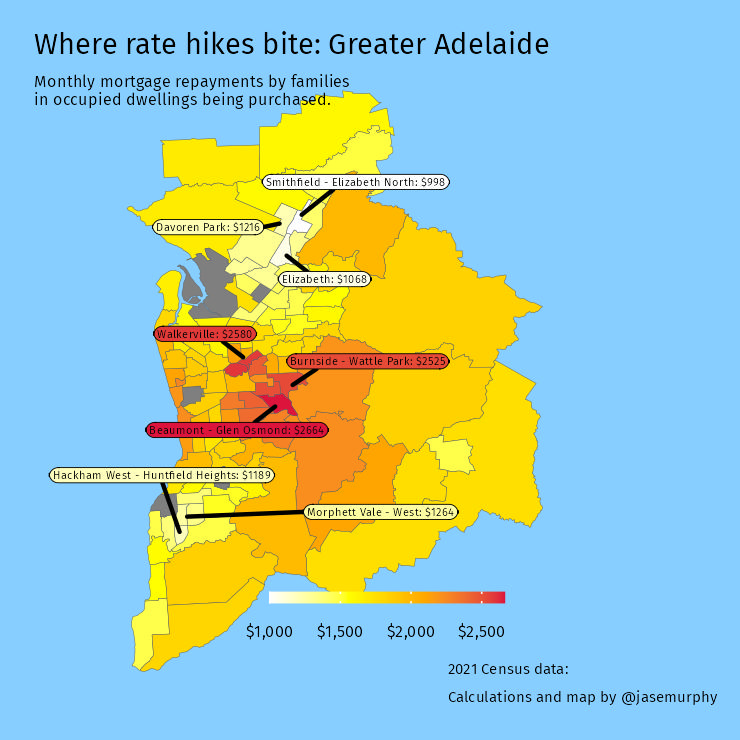

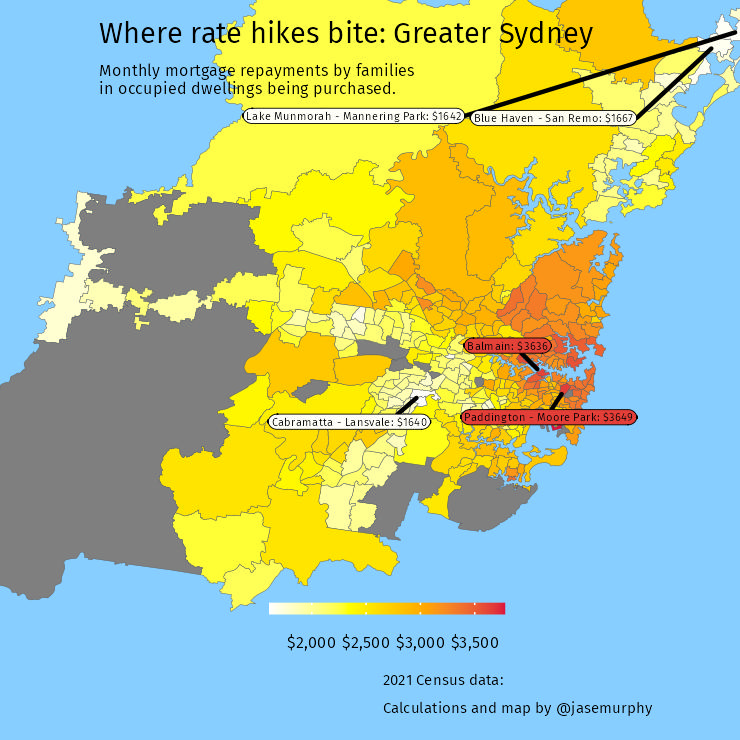

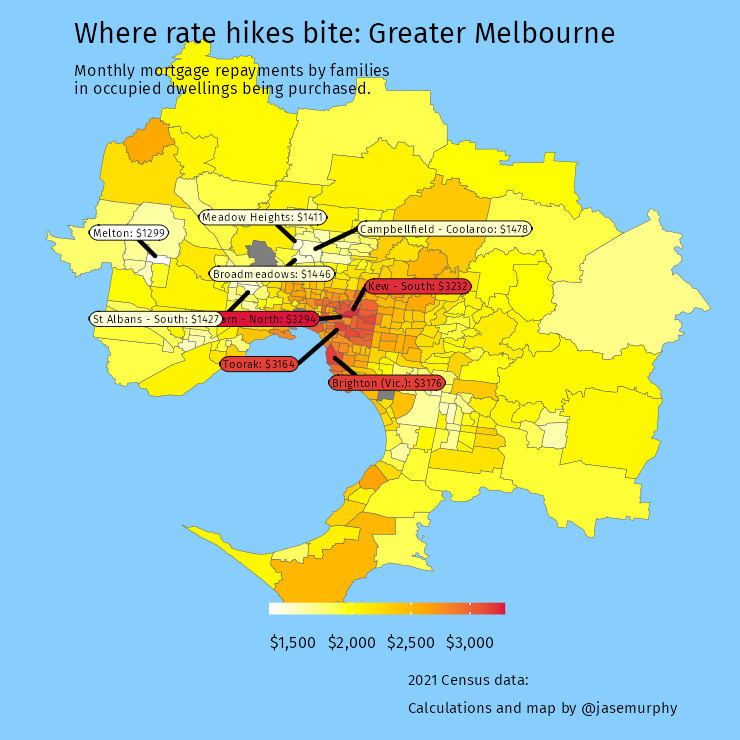

Who are these people? I mapped mortgage payments by suburb for Australia’s cities and the answer seems to be that big mortgages don’t map onto the wealthiest suburbs. But they are found in the suburbs nearby. The maps below use a colour code to show which parts of the city have the highest mortgages. Labels are applied to suburbs from the top and bottom of the repayment spectrum.

The highest mortgage repayments in the country are found in the ACT and Sydney, the maps reveal, and the lowest are in northern Adelaide.

But of course a high mortgage is no big deal if you have a high income. Where are mortgages highest as a percentage of local incomes? The following maps show that it’s not always the same areas where mortgage repayments are highest.

The Sydney map is instructive — in Cabramatta, household mortgage repayments are towards the top of the scale compared to local personal incomes, while in Balmain repayments are low compared to local personal incomes.

(Note that this is an indirect measure of mortgage stress. Households with mortgages in an area contain a subset of those whose incomes are measured and may have different characteristics — younger than average in areas that tend older; older than average in areas that tend younger; richer than average in areas that are diverse and have a lot of public housing; more likely to have multiple incomes in the household, etc. The percentages do not tell you how much of their income a family is spending on their mortgage. Consider it as a probability indicator for mortgage stress for people in that area.)

Still, the pattern is consistent in Melbourne as well: well-off Brighton has one of the lowest shares of mortgage repayments compared to local income, while Broadmeadows (battler territory) is towards the other end of the scale.

Did the banks not factor in the possibility of interest rate rises when assessing how much they could loan to buyers?

Has the absurdly low interest rates of the past several years lead to absurdly over-priced properties?

There is a legislated interest rate buffer that they have to apply when assessing how much to lend – some more conservative lenders have an additional buffer on top of that. I think the buffer is 3% above the rate offered to the customer.

Part of the problem is that when looking at affordability – the living expenses (everything basically except debts) is largely based on self assessment by the borrower – so can be markedly lower than their actual expenses, though there is a floor to that which is the Household Expenditure Measure or the Henderson Poverty Index, which is respectively the average that someone in the circumstances would be expected to spend on their expenses, or the amount someone in the same circumstances but just above the poverty line would spend on their expenses

So a borrower in theory should be able to afford (all of) their buffered loan repayments, and at least as much as someone in poverty on their expenses.

Homeloan Applications are also only at a point in time. Borrowers situations can, and very much do, change.

Oh for sure – the idea that you can decide that a 500k+ debt is going to be affordable for someone on a 30 year loan term is crazy.

Hi Jason. Is Brisbane mortgage-free? Not me experience with the bank taking its pound of flesh every month.

This is a national publication so Perth, Hobart and Darwin must also mortgage free. Perhaps a notation in the narrative, to explain this. Perhaps theses forgotten states didn’t suit the narrative.

Interesting when you drive around new suburbs that nearly all the houses have at least one rather new looking motor car in the drive. Possible to cut back on these too surely.

20 cent deposit and road to ?????? a bit like the policy by Smirky and Joshy.

One thing I can say about the issues in this article. The borrowers at least have jobs and seemingly secure ones. I wish I had that when I took out my first home loan back in 1989. It was very hard for me in the 1990s with various jobs. In 1990/91 FY, I earned a touch over $18,000 and my loan was around $78,000 and interest rates well into double digits – 13-14% maybe. Just trying to introduce some relativity. The day I settled on my first home in Sydney in May 1993 I got sacked from my job and then went to get the keys off the real estate agent but not before registering at social security for unemployment benefits. The house was in a flood prone area than too which we thankfully vacated over 5 years later with no incident. And with a secure govt job to boot but geez it was a struggle. I can only think how house prices are going to tank if unemployment rises to above 6%. Also to give some perspective on this as well, the rate for unemployment was 8.5% in December 1990 (the recession we had to have), 11.3% in 1993 when I moved back to Sydney and purchased a house in the flood plain, 8% in 1996 when Keating left office.

Here’s hoping for no recession otherwise today’s kids will be grandparents when they leave home.