The average number of Australian Defence Force (ADF) veterans being hospitalised for intentional self-harm each year has nearly tripled in the past five years compared with the 17 years before, according to data revealed by a freedom of information request.

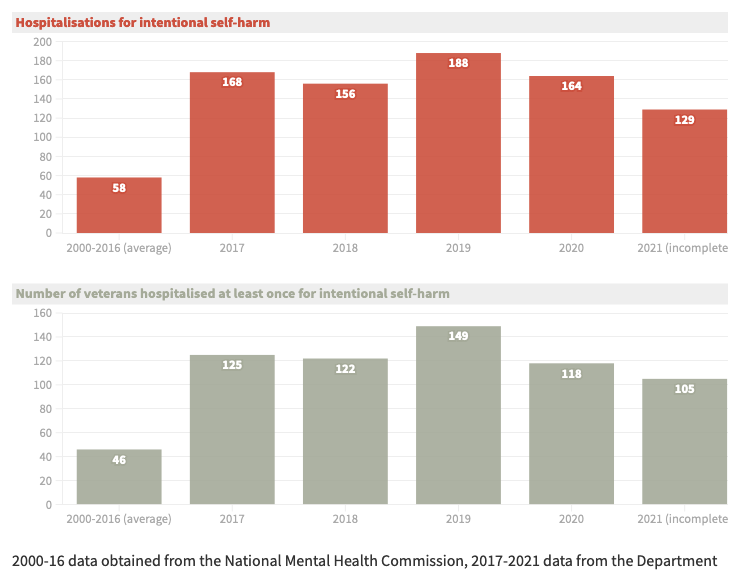

The Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) recorded 805 hospitalisations for intentional self-harm by 554 former serving members from 2017-21. The final year’s data is incomplete as some state governments have yet to report, it noted.

The National Mental Health Commission’s review into the ADF reported that there were 986 hospitalisations for intentional self-harm for 789 members between 2000-16. A year-by-year breakdown wasn’t published, but the average number of hospitalisations each year in the past five years is nearly three times what it was in the preceding 17 years.

The most recent figures are based on hospital admission data for veterans of all age groups in both public and private hospitals where a DVA-funded treatment entitlement was used. Admissions data does not distinguish whether the self-harm was accompanied by suicidal intent, but does include incidents where the self-harm was not the reason for admission. Factors such as changes in the number of people who can access DVA funded treatment and growing awareness of the services may influence rates as well.

The 2017 ADF review wrote that previous studies of lifetime prevalence rates of self-harm in serving and former military members are between 2.3% and 12.3%, compared with a general population rate of 4.9% (noting that comparisons between the military and general population are difficult due to data limitations).

Australian veterans also suffer higher rates of suicide. A 2021 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare report found that Australian male and female veterans were 24% and 102% (or 2.02 times) more likely to suicide than the general population between 2001-19.

Minister for Veterans’ Affairs and Defence Personnel Matt Keogh told Crikey that figures of suicide and self-harm in serving and veteran ADF members greatly concerned the government.

“Unfortunately, for too long and even today there remains a stigma around mental ill health, which has meant veterans have been reluctant to seek the help they might need,” he said. “I encourage serving personnel and veterans to seek help if and when they need it.”

Keogh said he looks forward to recommendations to improve the well-being of current and former ADF members made by the royal commission in its interim report later this year and its final report in 2024.

In the meantime, the Labor government has pledged to build 10 veterans and family hubs, $24 million to veteran employment programs, and $30 million for veteran homelessness.

The royal commission is conducting hearings around Australia this year and is accepting submissions until October 13 2023.

Free, confidential counselling and support are available to all current and former serving Australian Defence Force Personnel and their families through Open Arms — Veterans & Families Counselling. This support is available 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Open Arms can be reached on 1800 011 046.

Lifeline 13 11 14, or www.lifeline.org.au; Suicide Call Back Service 1300 659 467, or https://www.suicidecallbackservice.org.au; Beyondblue Support Service 1300 22 4636, or www.beyondblue.org.au

Tragic. The result of hanging on to the coat tails of the USA in stupid wars such as Afghanistan. Did it help them? No. Did it improve our security? No. Did it even make sense? No, because 9/11 was an attack by Saudis. The same sort of garbage goes for the Iraq thing, and Vietnam (where I was). When will we ever learn? Back home, dealing with the DVA is like swimming in treacle, and for very, very stressed people it couldn’t be worse. Been there – a nightmare. A very long nightmare. To be or not to be, becomes the question.

Sorry to hear that drastic, it sounds like DVA itself wants an overhaul – it’s probably overworked folks with not enough people trying to do their best.. A serious workcare accident is similar, in that for already super stressed seriously injured people are triply stressed by the adversarial, “doing anything to reduce costs” nature of the process.- which includes deliberately not telling you what you’re entitled to. Is DVA like that? Or it “just” a not enough people to do the job issue?

Meanwhile, the previous government secretly dumped another $50m into the totally unnecessary extensions to the Australian War Memorial. Cost now $548m and probably rising. Recommend folks write to Treasurer/Min for Finance to urge them to probe this boondoggle and rort as part of Budget preparation. Background is here: http://honesthistory.net.au/wp/an-agenda-for-albanese-4-time-to-rule-a-line-or-cut-back-on-this-unnecessary-and-obscene-war-memorial-project/

But… but… back in 18 Nov 2019. the ABC reported, “Shell-shocked veterans will have their post-combat trauma eased by a half-billion-dollar expansion of the Australian War Memorial, according to the institution’s outgoing director.” So that’s all right. And if you cannot trust Brendan Nelson, well…

Surely if the government said it was cancelling the project and putting the money towards veterans’ mental health, nobody could object?

DVA is a disaster. However, the ‘root cause’ question is ‘how can an employer (our military) treat its volunteer workforce in such a way that so many suffer long-term harm & consequences of their service to all of us?’

According to my ex army friend, “stigma around mental ill health, which has meant veterans have been reluctant to seek the help they might need” starts in the army itself – so I doubt that a civilian talking glibly about getting help is going to do anything to help. AND… is their access to mental health services as poor as everyone else’s?

I knew one marginal case, a conscript lad from the Vietnam era, crushed with associated guilt. USA “wars” are executive murders.