With the review of the Reserve Bank now launched by Treasurer Jim Chalmers, the array of vested interests, ideologues and axe-grinders that make up those who’ve pushed for a review will get busy on their submissions.

A key area for the review, to be conducted by Canadian central banker Carolyn Wilkins, Professor Renée Fry-McKibbin and veteran bureaucrat Gordon de Brouwer, will be the composition of the RBA board. Unions want a union rep; academic economists want an academic economist rep; The Australian Financial Review warns against any “politically correct” shift away from the board being dominated by business representatives.

Without extensive consultation with previous board members, it will be difficult for the review to gauge whether changing the make-up of the board, or the appointments process, will have a material effect on RBA decisions. Rate hikes during both the 2007 and 2022 election campaigns, along with Philip Lowe’s outspokenness on fiscal and wages policy, suggest there’s no problem with the independence of the board; the fact that Tony Abbott wanted to impose an outsider on the Bank to “fix” it suggests the presence of business leaders on the board has done the Liberals no favours.

Against that, however, it’s clear that the RBA has been far too optimistic about wages growth for far too long, suggesting a near-total detachment from workplace reality for Australian workers. Even now, the Bank continues its “just around the corner” act, insisting wages growth will start any time now (we’ll find out at the end of August whether it is finally, after nearly a decade, proved right, when the June quarter wage price index result arrives).

It’s possible that the presence of a union representative or labour expert might have provided some pushback against RBA staff’s relentlessly Pollyanna-ish forecasts over the past nine years, and enabled a more realistic view of the wage stagnation that has beset most workers to inform its view that monetary policy should remain more or less stable in the years up to 2019. In particular, someone with extensive experience in the vagaries of Australian wage fixation — it may not necessarily be a union official — could have explained how the EBA system has broken down in real time, rather than requiring the bank to eventually draw its own conclusions from the data.

To restate the problem, it’s possible a more representative RBA board might have brought more expertise to bear on an important datapoint informing monetary policy considerations.

Normally representation and expertise are quite separate aspects of the governance of any institution, and especially powerful ones. A powerful public policy body that perfectly replicates the community it serves but has no expertise will fail to serve the community; a completely unrepresentative body of experts might get the big decisions right but be regarded as out of touch and illegitimate. Moreover, we know that experts come with their own biases, and don’t always get it right anyway — especially when faced with a novel crisis like a pandemic. Somewhere in the middle is a sweet spot for both representation and expertise.

At the moment the board is embarked on the most significant decision-making course in decades — certainly since the recovery from the financial crisis, possibly since it intervened to belt the recovery occurring under Paul Keating in the 1990s. Both Lowe and his deputy Michele Bullock insist Australian households have the wherewithal to withstand a long series of rate hikes. They are informed by streams of data and their business liaison program (which so successfully informed all those years of optimistic wage forecasts).

If they get their calls wrong, criticism of how out of touch the RBA is will accelerate. Some political figures outside the mainstream stand ready to exploit such sentiment. Clive Palmer proposed to cap interest rates at the last election — a dramatic abolition of central bank independence. His failure — beyond a single Senate spot — shouldn’t blind us to the reality that community sentiment could shift against what might be portrayed as an elite financial cabal. After all, there are already plenty of wingnut conspiracy theories — with plenty of disgusting anti-Semitic overtones — being peddled on the far right and even in the Senate already about central banks.

More representation may or may not add significantly to the board’s expertise, but it might help offset such sentiment.

In relation to the possible appointment of a trade union voice to the Reserve Bank, I am struck by the historical myopia that pervades so much comment, especially from the likes of the AFR and Murdoch missionaries.

Whitlam appointed Bob Hawke to the RBA in 1973; Hawke was on the Board until 198i. Over that period he also served on the Jackson Inquiry into Australian Manufacturing, and the Crawford Committee which reviewed Australian trade. As a member of the RBA he would have been across the work done by the RBA in response to the Campbell Committee inquiry into the Australian Financial system, including the role of the RBA. His occupancy of those positions was sustained by appointments and reappointment by Malcolm Fraser.

I believe Hawke’s biographers, especially the most recent Troy Bramston, understate the significance of that experience in shaping the repertoire and policy insight that Hawke brought to his prime-ministership from 1983 on.

Effectively. he and a Cabinet amply equipped with economically literate members, implemented measures derived from that grounding in emerging neo-liberal economic settings but overlaid in with social policy priorities. Sir Fred Wheeler, Treasury Secretary is quoted by Bramston as commending Hawke’s contributions to the RBA as a Board member.

When the 1983 Economic Summit was convened, Hawke as PM acceded to a request by the ACTU to break with precedent. He and Keating allowed representatives access to as yet unpublished Public Account analysis.

The significance of that allowance is overlooked. In Bill Kelty, Jan Marsh and Rob Jolly, the ACTU had a working group capable of comprehending and making use of the information to which they were given access. That insight was a significant factor in those officers subsequent task of persuading their Executive and the union movement generally to accept the compromises intrinsic to the Prices and Incomes Accord that was one outcome of the Summit.

If memory serves me, Bill Kelty later served for some years on the RBA Board; if so, I have little doubt that he would have been considered a valuable member of it. Greg Combet should have been recruited to the Board. Of the current crop of union leaders Sally McManus stands out as a person of sufficiently high capability to make a worthwhile contribution to either the current RBA or its extension.

The historical reality is that there is a reciprocating benefit in the public interest to having well qualified Board members drawn from the union movement. Doyennes of economic planning and central banking such as Wheeler, Nugget Coombs and John Crawford, would I believe think it a no brainer to include on the RBA Board a competent, diverse set of leaders drawn from across Australian productive sectors including unions and the services sectors outside the academic and corporate sector.

It is farcical that the RBA board is so dominated by economists and business types. Those classes do not have a monopoly on sensible economic thought. That assumption is insulting to anyone excluded.

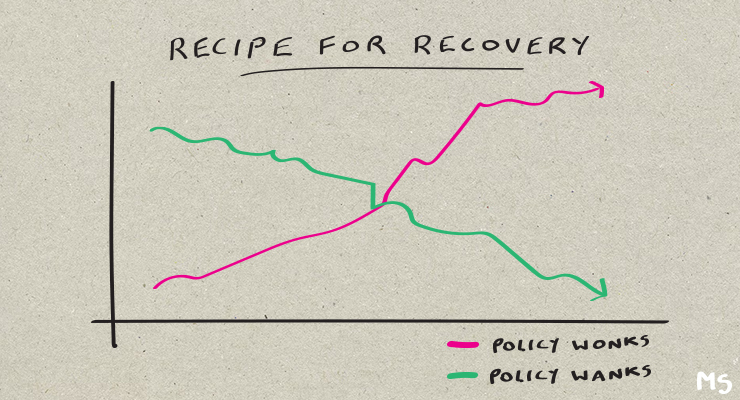

And as to the ‘expert’ point. Are you seriously ascribing any useful expertise to economists who purport to read the data and predict the future, almost always wrongly.

The most telling point you make Bernard is the utility of including those who have actual expertise and experience in how society really works and how economic action effects individuals. What we have now is a bunch of faux experts reading the data produced by social and commercial activity and trying clumsily to interpret the ‘economy’, not society. Why is there any doubt the RBA gets it so wrong so often?

Great point. It always astounded me that the self-named ‘best economic managers’ could not see that lifting welfare support to those most in need brings far greater benefits to the economy than a tax cut for companies and the very wealthy. Poorer people spend the extra money they get – rich people can always buy their own luxuries.

The RBA should not be dominated by business people, since they have expertise only in upraising business interests, which are contrary to the interests of workers, with some softening of that opposition among other than luxury retail businesses, since they are also interested in having demand for what they sell. Unions should be represented, since they could have objected to the assumption that wages would be rising.

In fact, contrary to the unsurprising view of business representatives, their interests are poisonous for what the RBA should be concerned with, now that we know that profiteering -raising prices higher than increases in costs-is behind a significant part of current inflation. For the rough tool of raising interest rates might well make inflation worse, of an increase in debt costs prompts businesses to raise their prices more. Certainly, Greg Lowe might hope that diminishing demand for goods on sale by increasing interest rates might crimp profiteering in retail businesses and this might undoubtedly have some effect among retailers that sell other than more luxurious goods. But an increase in interest rates will accelerate the run down of savings held by more wealthy families and that may increase the number of people subject to mortgage pressure and thus might intensify the threat of a downturn.

The complexities of the RBA’s blunt tool, speaks all the more strongly for the Government to take up Joseph Stiglitz’s good suggestion of a windfall profits tax. That proposal would not be something the ALP promised before the election but no government can afford to stick to what it said, when circumstances change so importantly. As Keynes once said, when the circumstances change, I change my views accordingly. Jim Chalmers and Anthony Albanese should take that view as a lead.

Totally agree with your comment about Joseph Stiglitz. He has studied extensively the global effects of neoliberal “trickle down” economic mythology, that has concentrated wealth UPWARDS to the 1%.

Current economic policy is STILL dominated by these myths.

Whilst Labor’s propsals for a “wellbeing” budget are admirable, they are ignoring the urgent need for change now that world events have introduced unexpected factors.

The RBA has admitted that interest rates are a “blunt instrument”, and it seems obvious to me that the vulnerable in our society will yet again pay the price for keeping the wealthy secure in their comfort zones.

The “legislated” tax cuts should be repealed and a windfall profit tax introduced so we can actually support those who are most affected by inflation, in particular welfare recioients who are now sinking even lower below the povery line.

If our RBA board only contains “experts” steeped in business ideology and neoliberal economic thought where GDP is the supreme measure of success, we will continue to see the application of “blunt instruments” where business outcomes are the primary concern.

I would love to see experts like Joseph Stiglitz as key players in these discussions. The perspective would be far broader. The inclusion of Sally McManus would also provide a broader perspective.

I agree that a union representative should sit on the Reserve Bank board. The question is, which union?

It would be relatively exceptional to draw a suitably qualified union official from other than a peak council, effectively only the ACTU. Kelty was a Board member from about 1987 to 1996 when he resigned on Howard’s election. Charlie FitzGibbon was a Board member prior to Kelty. FitzGibbon was an honorary ACTU officer but his union office was Secretary of the WWF. From what I knew of him, he would have been a suitable member because of his exceptional industrial wisdom , wide experience of industry and influence in union and political circles.

Should the RBA Board be more representative of the Australian population or left to the experts? Easy. More representative of course. The experts have failed us miserably. There should be more dissenting voices and reports. Let’s face it. The guy in the pub couldn’t have made more of a hash of things than Lowe.