Donald Hellyer is the CEO of OpenDirector and fintech development company BigFuture.

After 30 years, the superannuation fund industry has become enormous and now has a material impact on the Australian economy. Superannuation fund assets now exceed $3.4 trillion, some 35% larger than the whole capitalisation of the Australian stock market.

When Paul Keating and the Labor government implemented the superannuation guarantee in 1992, it also started the growth of industry funds. Originally these funds were to provide retirement for workers of a specific industry, but they are now “public offer” funds, meaning anyone can join them. Industry funds now have more than $1 trillion under management.

But superannuation fund governance, especially in industry funds, has not kept up with the rapid growth of funds under management. The most glaring example is how superannuation fund directors are selected and remunerated. Members rarely are given a choice to vote for directors, and in almost every case, superannuation funds do not disclose director remuneration in their annual report.

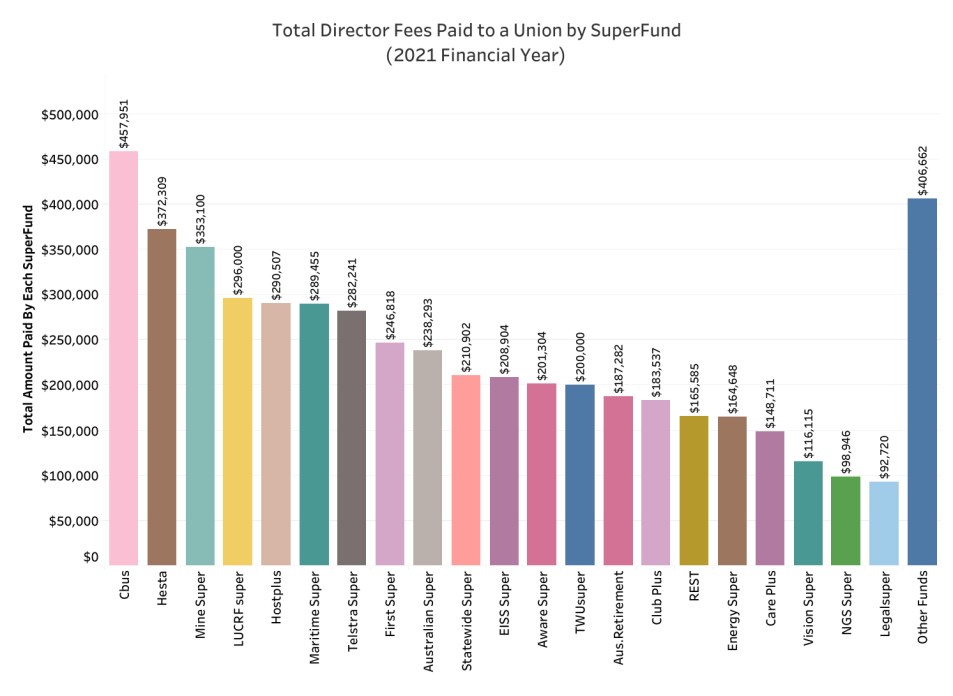

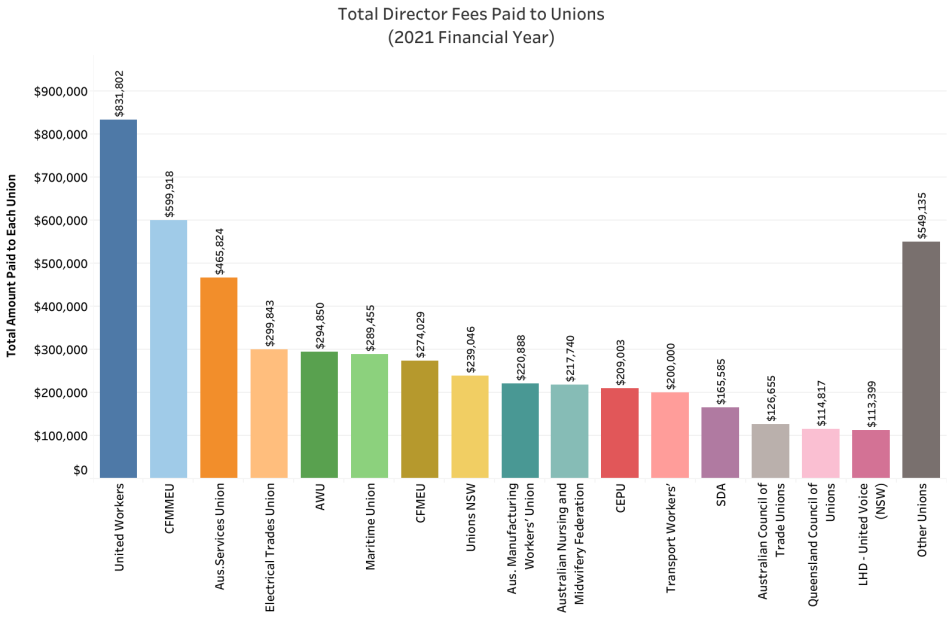

Industry funds appear not to have modernised their director (trustee) selection process, having institutionalised the number of union representatives on the board. Analysis by OpenDirector — Australia’s most comprehensive search and analytical online application covering the nation’s senior directors and executives — reveals that unions receive more than $5 million in board fees annually.

Cbus Super, the construction industry’s fund, paid $458,000 to unions as board fees. It also has 16 board members, which seems excessive given that even Australia’s largest public companies have only 12 to 13 directors. Is the high number of directors a result of having representatives from the many unions associated with the construction industry?

One positive is the apparent progress towards gender balance, with 41% of the 91 directors appointed by unions being female.

Superannuation board directors are not overpaid. The fees are modest. The fragmented nature of members also means a lobby group like a union can play an essential role in controlling management remuneration.

The criticism is that superannuation funds need to modernise their disclosure and transparency. The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is pushing for more disclosures, but superannuation funds should want to do this for the sake of members.

Full disclosure may create challenging questions for the superannuation fund. Still, the size and influence of the superannuation funds require that management and board be transparent as to what they are paid, for what services they are paid, and if there are any actual or potential conflicts of interest in payments. It wouldn’t hurt to have members vote for directors.

Mr Hellyer appears to have missed the memo which told everyone that Industry Super Funds have Boards comprised of an equal number of union AND EMPLOYER representatives. Oooooops! Has he assessed the fees paid to the employers yet?

Yes we did and the amounts paid are very low. The issue is not the amounts paid, as the article says they are modest. The issues are disclosure and governance modernisation. All funds, be they industry, government or retail, should disclose what executives and directors are paid. Importantly as the funds consolidate the old ways of institutionalising director seats are no longer appropriate. This is especially the case once funds become “Public Offer” funds.

It might also be good to look at the comparison between what board fees are paid for other industries – I would imagine Industry Super would be right down there!

Then explain the headline and the repeat of it relatively early in the article. Very The Australian-esque in style.

And the fact that under equal representation boards need a 2/3 majority for decisions, and almost always operate by consensus. Having said that, no harm in greater, clearer disclosure.

Yes, if Crikey would let me comment instead of only being able to reply to comments, this would have been my thing – this article is transparently one-sided.

Crikey, we’re happy with you not printing anything at all (it’s not like you have a news hole to fill) than run garbage like this. This makes Madonna King articles look well researched and edited.

I’m very happy for unions to get plenty of fees from their work on industry super boards. At least we know unions represent the rights of working people more than their employer counterparts on those boards.

Just another union bashing exercise.

By law, HALF the Directors on profit for members Industry Super Funds are EMPLOYER representatives (e.g. The Master Builders Association or Australian Industry Group AIG). This misleading article should have the headline: Employer and union Directors split $5m in fees.

Of course, on the for profit Retail Super Funds ALL the Directors are banking/insurance representatives receiving those Director fees from members in addition to the profit being made from the investment of the members’ super going to the owners. But we never read about that….

Shame on you Crikey.

The article isn’t intended to be union bashing. The article says, “The fragmented nature of members also means a lobby group like a union can play an essential role in controlling management remuneration.”

This article is about disclosure and the modernisation of governance.

Just to clarify your comments about laws governing “Industry Super Funds”, under S89 of the SIS Act 1993, the Equal Representation requirements apply to any fund that meets the definition of “Employer Sponsored” under Section 16 of the SIS Act 1993. In other words, if a single Employer contributes to a superannuation fund it is an Employer Sponsored Fund.

The term “Industry Superannuation Funds” is not an official type of superannuation fund under the SIS Act. In other words, the Equal Representation requirements apply to any Employer Sponsored Fund, not just “Industry Funds”.

So what?

Directors are drawn equally from employee representation and from employer representation. An article that completely disregards the employer board members, and treats board fees to employee reps as contributions to unions while fees to employer reps are … well … doesn’t pass even as bad journalism. It’s just anti-employee propaganda.