This is an edited extract from Empire, War, Tennis and Me by Nobel laureate Peter Doherty, published August 2 (MUP)

With few who fought in WWII still alive, those of us who were small children through 1939–45 will soon be the last who remember them as young men and women. Homes are sold, and memorabilia, photographs and so forth that meant a great deal to one generation become, without an attached story, meaningless to the next. If you have a relative who served in WWII but are only vaguely aware of what they did or what they endured, it’s worth paying the few dollars to get their records, their service and casualty forms from the Department of Veterans’ Affairs. Unless there are old letters, these provide, at least for those few warrior years, a much more detailed account than any other you might find.

The world of empire and duty that these ordinary and extraordinary men and women inhabited is now as historical as Davis Cup amateurism and wooden tennis racquets. We will never know all the facts about such men, and it may well be better that much of the agony they endured is lost to history. But we may just possibly understand ourselves, our families and our country just a little better if we take the trouble to meet them and confront what they experienced.

Still, why write a book on empire, war and tennis? Why make the effort to travel this particular byroad?

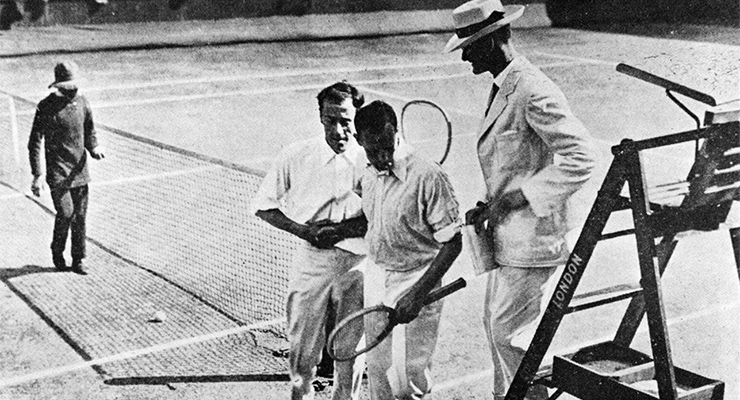

The journey began with the story of my mother’s family, the Byfords, and the lives they lived before, during and after WWII. My uncles Charlie and Jack Byford were keen tennis players who, with absolutely no prior military involvement, volunteered in 1940 to fight for Australia and Empire. Theirs was the experience of so many in the great civilian-soldier conflicts of 1914–18 (WWI) and 1939–45 (WWII)

An infantry private, Jack was in the front line at the Kokoda/Buna–Gona, Markham Valley/Finisterre Range and Balikpapan campaigns. Charlie at first had an easier time as a paymaster staff sergeant, but then suffered the experience of being a prisoner of war on the Thai-Burma Railway. Back in about 1929, the two brothers got together with my grandfather Bert and friends to construct their own ant-bed tennis court. Born in 1940, I’ve long thought of that slowly degrading court as both a memorial to them and a symbol of a very different and now disappeared time.

While my initial idea was to write a book focused on tennis and war, reading into the subject soon led to thoughts about national aspirations, national pride and international competition in peace — tennis — and war. The story of the first 70 years of lawn tennis (1875–1945) is embedded in much bigger narratives about imperialist ambitions that led to smaller conflicts and then to both WWI and WWII. Through that timeline, the imperialist nations that are of particular interest from the Australian perspective are Britain, Japan and the United States, with France, Germany and the Netherlands being more minor players.

Lawn tennis spread rapidly through the various colonial dependencies. Requiring only two people for a spontaneous hit-up, it was the perfect fit for Europeans who found themselves marooned for a time in hot and alien places. A few games over an hour or less at the end of a tiring day were a perfect prelude to showering, drinks and dinner. Designed to keep the colonised at a distance, the exclusiveness of club memberships led to the rapid emergence of parallel tennis cultures in the upper echelons of local ethnic communities.

Now, readily viewed via our TVs or handheld devices, the top tennis matches attract massive audiences. People love, I think, both the gladiatorial and the nonviolent character of the game. What’s thankfully gone is any hint of racism, sexism or cultural divisiveness, at least within the official tennis culture.

The ancient land of Australia was firmly under British control by the time lawn tennis came on the scene. Through the 1880s, both tennis clubs and intercolonial tennis championships were increasingly part of the social mix. Then, from the 1899 completion of the undersea/overland telegraph line linking the colonies to imperial HQ in London, sporting results were immediately transmitted and widely reported in the newspapers of the day.

By the time the first Australian federal Parliament met (1901) in Melbourne, the International Lawn Tennis Challenge (now known as the Davis Cup) was already established, while Wimbledon was recognised globally as the home of the sport. Lawn tennis had grown rapidly here. We were good at it and, even in those early days, it was a much more egalitarian pursuit both in this wide brown land and in neighbouring New Zealand than in most other countries. At first competing in partnership with New Zealand, Australia had many Davis Cup and Wimbledon triumphs to its credit by the time our seat of government moved to the bush capital of Canberra in 1927. With ups and downs as top players came to the end of their sporting careers, that pattern continued through until 1939 as WWII began.

Like any other sport, or any other cultural activity, tennis developed as an expression of its society. The tennis world reflected the larger world it was part of, with that world’s prevailing social conventions and ideals. But as with any other social activity, also, the “meaning” of tennis could be shaped, by those who played or were involved in it, in ways that worked against the winds of history or, less poetically, against society’s most powerful agents of change.

Looking back across the experiences of earlier generations, we can see that ordinary people were in many ways the mere playthings of larger historical forces over which they, individually, had little control. They were however able to carve out spaces for recreation and pleasure, even in humbled circumstances, and means of connecting with their fellow humans, in play, in ways that didn’t involve ongoing domination or exploitation.

The story of tennis, within empire and war, may teach us as much about the past and the future as the study of those larger monuments to human aspiration and folly.

In the future, if we have any sense, we’ll work together, focus on real problems, defuse our inherent tribalism and settle for combat on the football field, the golf course, the cricket ground, the baseball diamond, the Olympic track or pool, the Rod Laver or Margaret Court arena, Roland-Garros, Wimbledon, or wherever. Tennis beats war.

Anyone for tennis?

Sorry but the sport vs war wishful thinking is a bit infantile.

In rural WA tennis courts and clubs were ubiquitous from the 1920s onwards – every hamlet and many ordinary farmhouses had a tennis court. Many can still be found now amid the weeds and broken-down fences. In my childhood (1960s) tennis was widely played on weekends by very many men and women and tennis clubs were very social places. In winter tennis players turned to football. Tennis wasn’t specifically for the gentry, although they also played – but polo was more their thing. Tennis in the Raj and tennis in country Australia might superficially look the same, but they occupied rather different social strata.

For sure. My parents, both public school teachers, met playing tennis.

I suspect that people who equate sport and war have not been near a war.

The author seems to be aware that Australia is about the only country where tennis was a widely-played, popular sport before it went pro in the 70s. This totally undermines his tribute. Australia tends to shine in the rich white peoples sports, not the ones that most people care about.

After serving as a bomber pilot in WW2 Dad played a lot of tennis, as did many others in England. Also golf and badminton. Cards were popular in the evenings. Mum did all that, plus hockey and lacrosse. Having taken on a big mortgage they were certainly cash poor. People play sport because it is cheap, surely, and social. I don’t play tennis much any more, but I still have my Ken Rosewall wooden racket just in case.

My own theory is that human men are genetically disposed to hunting and warfare. Golf is a way of practicing hunting, while team sports practice warfare. So sport and war are part of who we are as a species, like it or not. Weird. In this inter-glacial we have taken to farming, but it won’t last.

My father Roy Wotton was an Anglican chaplain in New Guinea in WWII, on Kokoda twice ( 53rd Militia Batt,) and then Gona, Sananda & Balikpapan( 2/12 batt 18 Brig, 7 Div). I wonder whether Jack Buyford ever came in contact with him