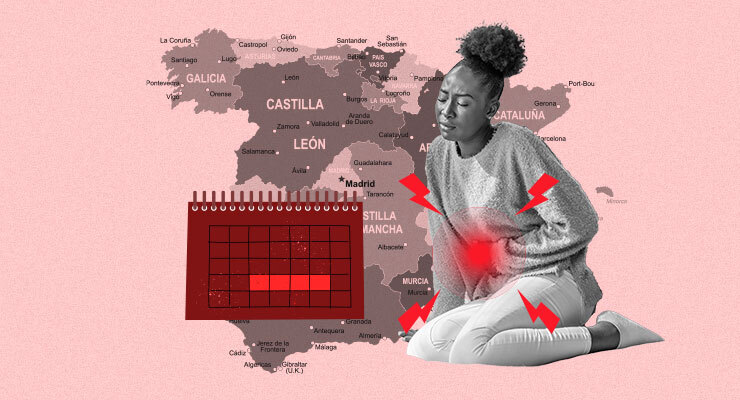

Spain has experienced a period of legal innovation. Literally. It has proposed a bill that would make it the first country in Europe to offer menstrual leave.

Introduced in May, the bill, which would also expand abortion rights by scrapping parental consent as a requirement for 16- and 17-year-olds wanting to terminate a pregnancy, would give workers who suffer from severe period pain three days of optional medical leave per month, paid for by the state. An additional two days are permitted in exceptional cases, for example for endometriosis, the condition where tissue similar to the lining of the womb starts to grow in other places, such as the ovaries.

The equality minister, Irene Montero, said that it should “no longer be normal for women to work in pain”. The bill has been approved by the cabinet and will now go to Parliament for debate. The government hopes it will become law by the end of the year, marking the end of a process that began last year.

In April 2021, the Spanish city of Girona became the first city to consider a menstrual leave policy for its 1300 employees. Other municipalities soon followed in its footsteps. When it came to women’s rights in the workplace, Girona was forging a new path, said its deputy mayor, Maria Àngels Planas, when the city council voted overwhelmingly in June to permit women who menstruate to take up to eight hours of leave a month. They would be required to make this up within three months.

Naturally, this proposal was not welcomed by all. Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT), one of the country’s largest trade unions, said the measure would limit women’s access to the labour market.

Bex Baxter, life and vocal coach and consultant for Coexist, a UK social enterprise based in Bristol, is familiar with this line of argument. She heard it time and again when she began crafting one of the earliest menstrual leave policies provided by a Western employer in 2016, six years before Spain’s bill.

Six years ago, Baxter had had enough — she just didn’t know it yet. At the Coexist offices, she saw a woman working in the reception bent double in pain, white as a sheet and still serving customers. Baxter, who at the time was the company’s people development director, advised the woman to go home, but she insisted she was fine and was “just on her period”. Baxter understood her pain all too well, having suffered debilitating periods with dysmenorrhoea herself.

Out of nowhere, Baxter felt a sense of clarity that was “almost biblical”, she tells me. She and the team started creating a menstrual flexi-time policy that included any time from between an hour up to one working day, anything more than this would then be counted as statutory sick pay (SSP). The idea, Baxter tells me, was that the missed time would be made up when the worker was feeling better, meaning work was completed to a higher standard. “The outcome was that people had more energy, working habits were more effective and productivity increased,” she explains. But the key element of Coexist’s policy is that “it isn’t one size fits all, the same as any flexi-time policy,” she adds.

The debate that Baxter and Coexist’s policy created was as ferocious as it was widespread. To quote her TED talk, “from Bristol to Beijing people were suddenly talking about periods”. But this doesn’t mean it was all positive. “I’ve had people — women — tell me I’m going to put feminism back by 100 years,” she says, explaining that some have told her this policy will be a detriment to women in the workplace, making them unattractive candidates to employers. To Baxter, these criticisms miss the point.

“That’s the thing about taboos. People count new ways out and comment on them without actually exploring it,” she says. Interestingly, Faye Farthing, communications and campaigns manager at Endometriosis UK, warns against a blanket policy and echoes Baxter’s position on the necessity of versatility. “A blanket policy risks downplaying the seriousness of symptoms that some of those with menstrual conditions, such as endometriosis and dysmenorrhoea, may experience,” she says.

“Rather than generic menstrual leave, we want endometriosis recognised for the chronic condition it is, deserving of the same support as any other illness,” she adds.

Endometriosis costs the UK economy £8.2bn (A$13.9bn) a year in loss of work and healthcare treatment, with the average diagnosis time for a woman taking eight years. In fact, research by the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) for endometriosis found that 55% of respondents reported having taken time off work often or very often, while 31% had reduced their working hours and 27% believed they had missed out on promotion. A survey conducted by the UK Parliament earlier this year also found that, out of 2000 respondents, one in three women were missing work due to menopause. While Sadiq Khan introduced menopause leave for City Hall employees in March, nationwide productivity levels appear to be crying out for a solution.

In 2017, a survey conducted in the Netherlands and published in the British Medical Journal found menstruation created similar obstacles. Out of 32,748 respondents, 14% said they took time off work or school because of pain during their periods. Others said that they showed up in discomfort and struggled to work during symptoms which, the study found, caused a loss of 8.9 days in productivity levels each year.

And yet, Spain’s bill is a European first. However, this is not for lack of trying. In 2016, the same year Baxter devised Coexist’s policy, four female Italian politicians proposed a bill offering up to three paid days off work each month for periods. The reactions were mixed, to say the least.

Marie Claire’s Italian edition described the policy as “a standard-bearer of progress and social sustainability”. But critics said it would create a disincentive for companies to hire women at a time when Italy ranked only 117 out of 150 countries for economic participation and opportunity in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap report. It failed to advance in Parliament.

The concept of state menstrual leave originated nearly a century ago and, unlike in Italy, was able to gain traction in a somewhat unlikely place: Soviet Russia. In the 1920s and ’30s, menstruating women were relieved of work during their periods in an attempt to preserve their fertility. In the 1930s, this idea also gained traction with trade unions in Japan and was legalised in 1947.

Today, the policy varies across Japan, from the time allocated to how it is paid for, which is negotiated between unions and employers. But it seems evident that taboos around menstruation and related workplace procedures are still present. In 2014, a study found that fewer than 0.9% of women surveyed in workplaces with a menstrual leave policy availed themselves of the policy, citing embarrassment or a lack of understanding on the part of male superiors as their reasons for not doing so. This is undoubtedly a concern for those both in favour and against menstrual leave. There is a big difference between a policy existing and its uptake.

“We need to challenge the historic squeamishness and silence around menstrual health and have more open conversations on this issue,” says Farthing. She feels the policy being discussed at a governmental level in Spain can only be positive and is eager to see a similar debate in the UK.

Aunt Flow. The red tide. Having the painters in. The time of the month. Shark week. Lady time. The crimson wave. Bloody Mary. On the rag… There are over 5000 slang terms for that dreaded six-letter word: period.

In 2016, a study was conducted by Clue, a menstrual health app, with the International Women’s Health Coalition to gauge how menstruation was discussed publicly. Around 90,000 people in 190 countries responded and the survey came up with terms across 10 different languages that 78% of respondents said they used.

Marks for imagination went to Denmark where the phrase “Der Er Kommunister i Lysthuset” was popularised. It translates as: “There are communists in the funhouse”. The French opted for the ever-so-slightly more political “Les Anglais ont debarqué”, which means: “The English have landed”. But the findings were clear: when it came to talking about menstruation, euphemisms were the method of choice.

When I bring up some of these expressions with Baxter, she rolls her eyes. “We need to change the culture and language around menstruation,” she explains. How can this be done? We need to start saying the word “period” more, she tells me.

Workplace policy aside, this point from Baxter makes my ears prick up. I share a memory with her: when I was at school, a sanitary pad fell out of my bag during a lesson. This apparent catastrophe soon caused a game of Chinese whispers desk to desk before reaching me. Upon realising what had happened, I kicked the pad under my bag and opted for denial when anyone asked about it. “It wasn’t mine!” I insisted. It is only with hindsight that I realise the words “period” or “sanitary pad” were never actually uttered.

Baxter nods. “My mother was part of the generation where when she first got her period, she thought she was dying. Her mother instructed her to look in the box by her bed and all she would need would be in there. It was never spoken about again,” she recalls. Baxter is tired of this stigma and feels it is well deserving of debate, and a policy, in its own right.

“This is why I am so excited about Spain looking at this at a nationwide level,” she explains. “It will give us access to hard statistics and evidence that we haven’t had before.”

By Baxter’s own admission, it is hard to gauge the overall benefits of menstrual leave while policies are so fresh. Yet the debate can be boiled down to two lines of argument: the logistical and the societal. The former refers to the mechanisms of a menstrual leave policy: how much time off is permitted and how it is paid for, and the practicalities of both are still very much up for debate.

The latter, however, tackles the stigma around periods, aiming for a world where, from classrooms to offices, periods can be mentioned openly in conversation without fuss or nauseating awkwardness. The debate around the first will continue, but the second is an idea to get behind. Period.

Should workplaces introduce menstrual leave? Let us know by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

Looks like older women [postmenopausal] will find it easier to find employment- so ageism will become a nonissue – things do balance out.

What i’d like to know is – what is this apparent epidemic of endometriosis all about?

Under, or non, use – as with nuns having by far the highest breast cancer rates.

The Pill is also thought to be implicated due to the 21 days then pregnancy mimicking action of the oestrogen then ceasing for a week then recontinuing so that sloughing off the cells is hampered.

Not to mention the higher infection rate associated with IUDs as the body tries to fend off the foreign body.

As was pointed out decades ago, nothing should be introduced into the vaginal canal unless sterile or at least boiled for several minutes in a suitable antiseptic – carbolic acid is highly recommended by some.

Speculation. Where’s the research?

Isn’t ‘period’ also a euphemism, as a metonym for menstruation (as in ‘a period of menstruation’)?

It’s barbaric that routine menstrual leave didn’t become a commonplace employment entitlement long before other now-unremarkable leaves, like maternity, parental, domestic violence and sick leave. The comment about ‘putting feminism back’ is instructive. There may have been early pragmatic utility in reformers defining feminism’s advance solely against masculine benchmarks but it’s had the cumulative effect of quarantining from any sensible policy discussion issues like this, and others turning on fertility, motherhood, and child raising. Such as whether or not many/most mothers actually ‘want’ to relinquish their kids into childcare.

Forget the old joke about awards and competitions…if men menstruated what we would prioritise is making sure we were paid hardship money on the job at worst, and preferably paid to just lie in bed for five days every month and whimper. This is about labour exploitation, really, but I doubt millennial feminism will let itself have this argument in any such terms (if at all). Younger feminists are nowadays too busy trying to convince themselves it’s fun making themselves unhappy trying to be better at being men than men. (Which is a fairly dismal ambition in the first place, if you ask me.

The really tricky part for the Spaniards could actually be whether or not women who have penises will be entitled to this leave. I’m not being facetious, by the way. It will be a genuinely live question. The range of biological female experiences of menstruation is itself infinite.

Very good to see this excellent story/issue get an airing here.