To understand who holds sway in Australian health policy, take a look at the federal government’s new taskforce to improve the quality of primary healthcare. Well over half of the Strengthening Medicare Taskforce members are practitioners and providers. One solitary member represents patients and consumers (and therefore the general public).

The idea behind the taskforce is sound. Considering the eye-popping levels of medical practice variation, that about 40% of Australian patients don’t receive evidence-based care, and rising out-of-pocket costs, improving the quality of primary healthcare is an urgent priority.

But what solutions can we expect from a panel representing predominantly the supply side of this equation? What is the Australian Medical Association (AMA), which has two former presidents at the table, likely to say?

How much clout will the one solitary consumer representative have at that table? Leanne Wells, former CEO of the Consumers Health Forum, is formidable and highly respected. But who will have the real power — the one consumer or the cadre of stethoscopes? Where’s the back-up to even the playing field: the representatives of patients with mental health problems and chronic diseases who most need affordable, integrated care? One hopes that the other non-providers (academics and public servants) will balance things out.

This isn’t about optics or symbolism. It’s about setting the taskforce up to drive real change in a broken system.

At least Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (ACCHOs) are represented by deputy CEO Dawn Casey.

In fact, Dr Casey could probably teach the chaps from the AMA a thing or two, because the community-led ACCHOs are recognised as the gold standard in delivering comprehensive and high-quality primary health care to vulnerable and complex patients. They’re highly effective and deliver value for money.

As if on cue, the final evaluation of the “Health Care Home” (HCH) trial (which ended in 2021) was recently published. It provides some insights into the challenges in primary care. In essence, the HCH aimed to deliver more coordinated and patient-centred services, and reduce unneeded hospital admissions, through two main levers: the voluntary enrolment of patients to a general practice — their health care home — and a bundled payment for every enrolled patient based on their clinical complexity (as opposed to a fee for each individual consultation or service). It represented a radical departure from the way primary care is currently provided in Australia: patient “choice” and, more significantly, fee-for-service (FFS).

The HCH was a laudable initiative. But the evaluation found “no significant change in patient experience, health care use outside of primary care or health outcomes”.

The assessment of the bundled payments is telling. ACCHOs found the payment “viable and appropriate” — unsurprising, given these organisations already offer a team-based approach that involves several health professions and disciplines. ACCHOs already are de facto HCHs and consequently achieve great results.

Elsewhere, however, this payment model (and the HCH more broadly) was a flop. Payments were either “insufficient to cover the additional work”, difficult to distribute between the GP and other practitioners, or both.

This is about as surprising as learning that pubs continue to serve customers who have had too much to drink.

The key problem is that a HCH is an all-or-nothing proposition. It requires not only radically different clinical but also administrative processes to succeed. Running part of a practice on this model and the rest on FFS would be difficult if not impossible. For providers, every minute spent on a HCH patient was a minute not spent churning other patients through on FFS, which is more efficient and therefore more profitable.

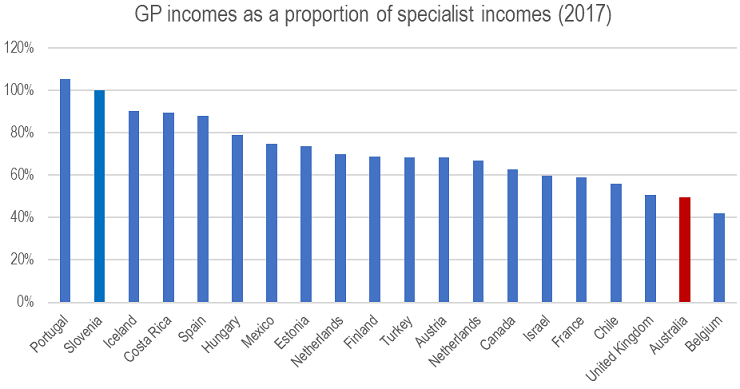

This is not to say that GPs and primary care providers shouldn’t be paid more, especially relative to other specialties.

It’s how providers are paid and what they are paid for that’s the issue. And in the end, it’s actually not about cost per se but about the health outcomes (the value) we, as a society, get from what we invest in Medicare.

OK, but what does all of this have to do with the taskforce?

Well, considering that (a) health needs and costs are growing, (b) Medicare and the healthcare system exists to serve patients and the public, and (c) evidence from here and abroad suggests (aside from a few exceptions like vaccination) that models incentivising volume and throughput are not compatible with better health outcomes, the taskforce may well conclude that instead of tinkering with a model that’s fundamentally ill-suited to modern demands, it might be better to build a new one.

In more tangible terms, the taskforce might recognise that the solution is hiding in plain sight and suggest that perhaps the ACCHO model is the most suitable option to achieve the aims of the review, and recommend a network of similarly structured and funded community-controlled health organisations throughout the country to provide better access to high-quality, integrated and affordable primary care.

Now that would be reform! Of course it’ll never happen because, as illustrated by the taskforce composition, we have institutionalised a political economy that creates a healthcare system designed around the needs of providers and not patients, especially not the most vulnerable and needy. Unless we tackle this power asymmetry, I doubt the goal of “highest priority improvements to primary care” can be achieved.

Correct. The system overly favours the providers, including big pharma, and they continuously lobby the govt to tweak the system in their favour. I am very concerned about the practice of conferences in this industry. Aside from being a tax rort, there is tremendous scope in conferences to reward doctors for favouring a manufacturers own products over a competitors oroducts. Rewards can include free tickets to the conference for spouses up to highly paid speaking engagements. This depends in part on big pharma knowing what doctors prescribe. What do we know about where prescription information goes and what is in that information?

I may quibble with the statement that “health needs…are growing”. Health wants may be growing eg the never-ending pursuit of cosmetic surgery treatments, IVF, expensive drugs for very rare cases, etc, but I question whether those things are actually needs. They use up scarce resources that are then denied to thousands of people with genuine needs. You want a luxury item, you ought to bloody pay for it, whether it’s IVF cycles, fake boobs, or optional surgery for the terminally ill or very aged.

Great article, but who is listening? Certainly not the vested interests or dumb politicians.

Lessons may be learned from the establishment of the NDIS. Here the beautiful principles and objectives of the NDIS Act were subverted by the prevailing vested interests. These incumbent institutions were overly represented and not able move themselves from the medical model of care they were expert in towards what people with disability were needing – a social model of care.

In addition primary healthcare is one part of an integrated healthcare system. No beneficial patient outcomes will be obtained until GP’s, hospitals and the other parts of the system that people rely on for their health are funded singularly by State or Federal government.

What does the federal government care if GPs are underpaid, underfunded and too few in number? It is the state that pays for the overflow to be managed in emergency departments.

A system with no single point accountability is almost always destined to fail.