At what point, if ever, will the Reserve Bank have its Wayne Swan moment and realise that continuing with its planned course of action will wreck the economy?

Swan’s first budget in 2008 was initially shaped along the lines of Kevin Rudd’s election campaign line of “This reckless spending must stop” and an inflation rate above 4%. A meat axe was to be taken to spending. But the treasurer, in Washington and New York, heard first-hand just how bad the early stages of the financial crisis really were. The meat axe was put away and replaced with a steak knife.

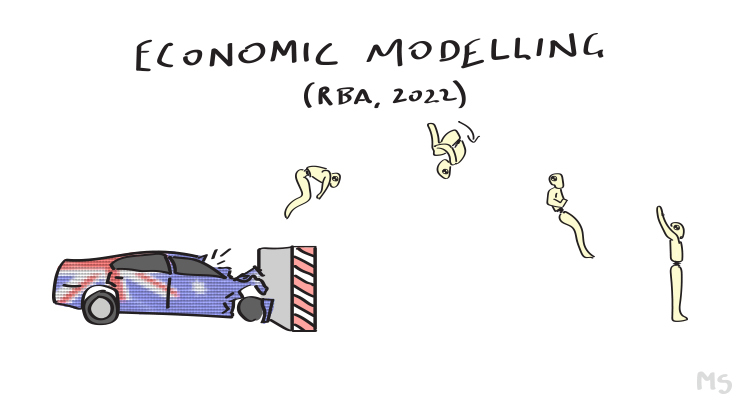

As Swan said at his media conference on budget day, the alternative was to “slam the economy into the wall” — just when global conditions were deteriorating.

It doesn’t take a trip to an IMF meeting to work out what’s coming for the global economy. Estimates of the probability of global recession range from likely to 98%. Even the World Bank estimates planned synchronised interest rate hikes will push the global economy into technical recession.

Unusually, the global recession will occur at the same time as China — one of the global engines of growth is having its owned sustained period of low growth caused by massive property market problems and its obsession with zero COVID.

Then there’s the small matter of the UK economy facing turmoil at the hands of its L-plate managers Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng, Vladimir Putin becoming increasingly frantic as he loses more ground in Ukraine, and the continuing impact of a super-strong US dollar on emerging markets.

But the RBA, so far, has shown no sign it’s for turning. Despite the lack of any wages growth and inflation being entirely supply-side in origin, it appears determined to knock demand into a coma, regardless of what will happen in 2023.

From the point of view of Martin Place, a recession might be ideal given unemployment in Australia is so low. No chance of the 10%-plus unemployment of the early 1990s — and anyway, that didn’t dissuade the RBA back then from lifting rates the moment the economy began getting off the canvas in 1994.

Consumer sentiment is poor — doubtless the significant fall in home prices has played a role there. The September house price report from CoreLogic on Monday gave the Reserve Bank more evidence the property market is slowing thanks to higher interest rates. The latest data showed the biggest fall in Sydney and Melbourne house prices since the depths of the global financial crisis. Australian capital city average dwelling prices fell 1.4% in September for the fifth monthly decline in a row. Including regional dwellings, which fell another 1.3%, national dwelling prices also fell 1.4% in the month.

But the poor sentiment isn’t translating into action: retail sales have continued to perform strongly despite multiple rate hikes as households continue to consume.

Moreover Australian energy and mineral exporters continue to ride a global wave of demand that as yet shows little sign of slowing despite the forecasts of doom. In fact, the Australian economy looks better placed than virtually any other developed economy to cope with a global downturn.

Even so, last week’s mayhem in the UK is a reminder that systemic malfunctions can emerge with a rapidity that makes the onset of the 2008 crisis look glacial. It’s only a few weeks since multiple European governments had to bail out systemically important energy trading companies, the collapse of which could have sparked another financial meltdown.

Economists think all this could help the RBA trim an expected half a per cent rise back to 0.25%. The AMP’s chief economist, Shane Oliver, says an unusual 0.40% increase would take the cash rate to a tidy 2.75% and allow for a final quarter of a per cent increase next month or in December.

Then we wait for that global recession to eventuate.

Awesome cartooning there 🙂

Regarding “retail sales have continued to perform strongly “, pardon my ignorance but I assume that is measured in dollars spent. As a mortgagor I have attempted to cut back consumption, but with inflation, it makes little difference to spending.

Having been made to look a complete idiot with his no rate rise until 2024 call, Philipe Lowe has been stung into a complete overreaction. And unless he starts listening to people who know what their talking about he will send the economy into a needless recession. One of the people he should talk to is John Aberhathy of Clime Investments who rightly points out that inflation will self correct even if there are no interest rate rises. Simply because inflation is supply driven. But no, he will mainly listen to people at the Federal Reserve in the US who also don’t get it.

I looked him up and he sounds interesting in that he thinks “outside the box”. What do you think he would contribute to this discussion though, given his focus on investment.

Watching this play out, I’m surprised the RBA keeps lifting interest rates on a monthly basis without measuring to see if the rate rises are having any effect on the economy. Each month it goes up a bit, ignoring the lag between when a rise happens and when it starts to affect consumers. So by the time we start seeing the effects of the first few rises, even more rises have been put into effect.

Obviously those in power know more about economics than I do (I would hope, anyway!), so maybe there’s something really obvious I’m missing. Maybe the measures are proactive, rather than reactive, for example, in which case why not do all the rises at once? In any case, from my layman perspective, it feels like they are acting without measuring to see whether what they’re doing is working. Perhaps it’s all an illusion created by the monthly cycle and media hype and this is the most sensible course of action, but it’s hard to see how it is in the absence of a link between behaviour and data.

Trusting that “they know what they are doing” has a bad track record in Australia. After the 1987 stock market crash, money shifted into a property bubble. The reserve bank ramped interest rates up 1% at a time all the way up to 19% for mortgages and 22% for business loans. Keating and the then Labor ministry were persuaded that these guys at Treasury and the RB knew what they were doing and talked of the J curve which would mean happy landings for the economy.

In fact, many small businesses went to the wall, mortgage defaults climbed like crazy and we had a really nasty recession engineered by the fact that genius economists at the Reserve and Treasury could not see that the impact of their measures would only reveal itself are some delay. Labor cabinet ruefully commented that they thought they had to trust the expert advice which was all singing of the same stupid song sheet.

There’s this generalised academic tendency to follow formula. “If this happens do that” It’s a substitute for observing the big picture, it bypasses rigorous thinking and allows them to say later when it’s obvious they were wrong – “we just followed the rules”.

I think that’s exactly the problem Kel S I don’t think they do know what they’re doing. I think they’re using rote economic formula instead of looking at the big picture. Either that or they simply don’t care about the pain they’re causing. The so called “inflation” is caused by dramatic rises in the cost of rent / mortgage, food, power and fuel – it’s not an overheating that’s caused by discretionary spending that can be “reined in”. So their rote formula is screwing us up needlessly.

On a slight tangent, it makes me wonder how much of this inflation is artificially created by companies realising they can raise prices under the guise that it’s due to inflationary pressures.

It’s funny that instead of the government trying to limit price gauging, it does it indirectly – by taking away consumer spending power forcing companies to limit prices to remain competitive. It’s a way that really puts the squeeze on people and causes a lot of unnecessary suffering, so it’s an economist’s wet dream!

That cartoon brings back memories for me, when I did something similar to that crash test dummy in the cartoon. It was 1976. I was riding a Norton Commando motorbike on Sterling Highway in Perth. A car turned right from the opposite side of the road directly into my path. I had no time to brake or avoid. I slammed into the side of the car at approx 60 KPH and launched myself over the car. Unlike the dummy, I stretched out like superman, and came down on my hands which I used to turn my momentum into a forward shoulder roll. (I had been doing some martial arts lessons and had practiced the shoulder roll many times). I rolled 3 times and came up onto my feet. Total damage: a slight graze on one knee (I was wearing shorts), and a compression fracture of my wrist. The bike was a total write-off. I decided not to ride motorcycles after that!

Sorry. I have nothing to say about the reserve bank, except generally agreeing with the tenor of the article and with other commenters

Reserve Bank says, “stop buying things, you’re causing inflation”, and so I have to shovel more money into the banks’ already profit-filled pockets.

State government says, “get back into the city and spend, spend, spend, never mind that local shopping strips are doing better because of working from home.”

Mortgage always wins.