The 2022 election ended up being a terrible mismatch. The Coalition had dramatically increased the level of spending during the pandemic, but was a reluctant and half-baked convert to big government; most Liberals still fetishised low taxes and passive government, and the soft and sometimes not-so-soft corruption of the Morrison government made much of its spending worthless anyway. It was big but hollow.

Labor has no such qualms about big government. The post-pandemic world — of interventionist governments, big deficits, onshoring and re-engaged public policy — suits it perfectly. The Coalition went to the election at odds with its own fiscal record, promising the old standards of lower taxes and fiscal discipline. Labor realised voters wanted government that was both more active and more competent and effective. On May 21, the Coalition showed up with a neoliberal knife, to find Labor had an interventionist gun.

The budget as a whole encapsulates that conflict — one the Coalition currently appears to want to perpetuate, presumably in the hope of being blown away in 2025 as well. The government of Anthony Albanese and Jim Chalmers is active, engaged and big — and it wants to assure voters it is competent. Its ambition is to be big and solid.

Thus the boondoggles and rorts are gone. Three billion dollars in “waste” has been hacked from various programs. Consultants and travel will be slashed in the public service. Billions in infrastructure spending will be “reprofiled”. Additional revenue has been banked, not spent, as Chalmers proudly boasted.

But there’s more paid parental leave, cheaper childcare and more aged care funding; more aid for the Pacific; vocational education funding; and a new Housing Accord to build more affordable homes near places of economic growth. And, of course, extra spending on the NDIS. Lots of it.

This is a government that does things, rather than one that announces things.

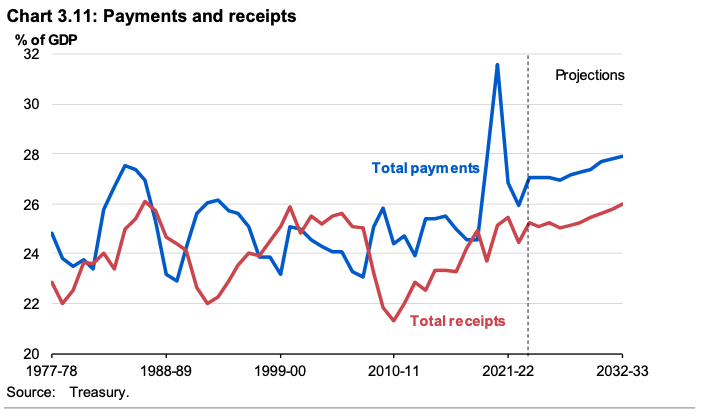

The result, though, is higher spending across the forward estimates, pushing it back up to 27% of GDP. By the 2030s, it will be closer to 28% — well above previous “emergency” levels.

Labor has to get the competent part of the spending right. If it does so, it will make its chances of a long life much better, while Australia will have — in a relatively short period of time — significantly increased the size of its government, with the support of voters. Unless the Coalition finds a different tack than promising tax cuts and fiscal discipline, it will be on a hiding to nothing.

But that doesn’t fix the other problem of how it’s all paid for.

The chart tells the tale: we’re only paying about 93% of our bills (which include the interest on bills we previously didn’t pay). The April budget suggested a slow narrowing of that gap between payments and receipts, but Labor insists that was based on wrong assumptions about the NDIS and bond yields. Jim Chalmers and Finance Minister Katy Gallagher say this is a much truer picture of our fiscal state.

The Coalition didn’t have the courage to try to address the gap. Labor says it will, but not quite yet. There must first be a debate about the issue — one that, at his media conference today, Chalmers declared he was happy with so far.

On the evidence since the election, delivering the competence — the solidity — needed for an electorally effective big government approach appears within the talents of the Albanese team. But closing that gap between spending and revenue, between ambition and means, will likely prove the sterner challenge.

The pathetic failure to take on big fossil fuel may yet come back to haunt the government.

The fact that the other mob wouldn’t have done it different-the same lame rationale used to restart mass immigration-is no excuse.

The upcoming conversation about tax can’t happen too soon.

Nor should reform require an election.

Don’t waste a crisis and all that.

You raise some good points there, Kim.

Although knowing the ALP, I wonder just how far this “upcoming conversation about tax” will actually go beyond a, ……ahh , well, “conversation”.

As mr gaucherie says, Labor can choose NOT to create debt. It can just pay for stuff, with money provided by the Reserve Bank, and stimulate a struggling economy in the process.

Turning Reserve Bank money into Treasury bonds is a holdover from another age. It is a subsidy of corporate bond holders and a burden on the people.

Although it’s called Modern Money Theory, this part is only describing the monetary system we already have. We could learn to use it constructively, instead of hobbling ourselves with a myth. Go and actually read Stephanie Kelton’s ‘The Deficit Myth‘. Or my favourite brief and clear explanation ‘The Millennial’s Money‘ by J. D. Alt. The federal government CREATES money, it does not have to borrow it. (Commercial banks also create money, but that’s another story, mostly to do with the wildly inflated property market.)

Inflation (due to government spending) will only be a problem if the economy approaches full steam, which it is far from at the moment.

The price increases that are being called inflation are better recognised as a real rise in the cost of doing business and the cost of living, due to supply issues. It is not a monetary phenomenon. Choking down credit through higher interest rates, and holding down government spending, only make things worse, especially for the battlers. The winners are the financial sector, whose ‘assets’ retain their value while real goods and services become more expensive.

Oh for a government and a commentariat that understand the monetary tool that is there to use constructively.

I don’t understand who we’ve borrowed the money (budget debt) from: China? : ))

Whoever holds government bonds, ie investors from all over, probably including your super fund.

Labor doesn’t HAVE to go into debt in order to spend on worthy projects. Of course they can CHOOSE to buy money and pay interest… or they can spend the money they can create. Inflation has already fired up, all courtesy of many factors OTHER THAN the influence of higher wages by and large. I wonder how many times in the past inflation has been more a case of wages chasing higher prices than the reverse?