While energy prices have suddenly grabbed the, um, imaginations of political commentators, and the vexed issue of whether a global energy price spike caused by the biggest war in Europe in 75 years is a broken promise by Jim Chalmers, there are nastier problems in this week’s inflation figures for the September quarter.

Specifically, housing construction costs.

New dwelling prices rose 3.7% in the quarter alone, for an annual rise of over 20%. The 3.7% was actually a fall from the June quarter, because the residential construction sector started weakening under the lash of RBA rate rises.

“High levels of building construction activity and ongoing shortages of labour and materials continue to drive higher prices for new dwellings. Although the rate of price growth eased somewhat this quarter compared to the highs seen in recent quarters, in annual terms, the series recorded the largest rise since it commenced in 1999.”

What’s worrying is that prices were still going up even when building approvals have come down more than 24% from their peak in March 2021, while housing loan approvals are — unsurprisingly — down more than 12% over the year to August. Usually, falling demand would put downward pressure on costs, but even now builders with fixed-price home building contracts are demanding more money from clients and threatening to stop building if they don’t get it.

And there should be a big fall in the cost of imported timber (even allowing for the weaker Australian dollar). Canadian and US timber companies are cutting production and laying off staff because of falling demand from the North American home building sector.

Even though we get a lot of timber from New Zealand and Asia, the US and Canadian industries exert a lot of pricing pressure globally. The average US lumber price is US$422.50 per thousand board feet, compared with a year or so ago when the likes of Bunnings were complaining about prices US$1500, or in February this year when they were about US$1300.

Rents went up too, at a faster pace than in the June quarter. Major cities other than Sydney and Melbourne saw rents rise by 5.6%, the highest level in a decade.

That meant, when combined with big gas price rises pushing up utilities costs, that housing costs overall rose 10.5% in the year to September, by far the biggest rise of any group in the CPI.

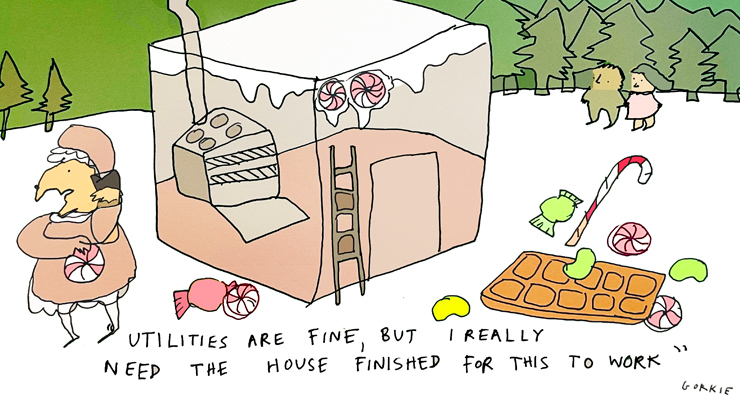

That rents are going up while the cost of new dwellings is going up points to an invidious problem: we don’t have enough housing, but building dwellings at the moment is very expensive.

And the comparative softening of construction cost pressures in the September quarter is something the government is keen to change — this week’s budget made a virtue of the 40,000 social and affordable homes the government plans to build, along with the nebulous “housing accord” that promises 200,000 homes a year.

None of those homes will start construction immediately — this is five-year plan stuff. But it reveals the distinction between the problem of energy prices — the product of external events, and a decade of policy failure by the previous government — and the problem of housing construction costs, where there are some external factors but much of the cause is our own ongoing demand, and moderating that demand is not a serious policy option — especially when we’re planning for more than 230,000 arrivals from overseas a year.

High construction costs resulting from supply chain issues and labour shortages are exactly the reason why state governments are slowing major infrastructure investment, something the federal government has now joined them in doing, with its reprofiling of infrastructure spending — a decision that also reflects an attempt to fix up the mess left by Scott Morrison’s tendency to announce first and worry about actual delivery later.

But on housing, it’s full speed ahead, with politicians, the construction and development industry and investors agreeing we need to be building more homes as quickly as possible.

Perhaps the government’s plan to make housing policy more coherent, including reestablishing a national housing supply council, can tackle the issue of how we accelerate residential construction without accelerating inflation even more. For young people looking to buy a newly built home, answers can’t come soon enough.

Full speed ahead? Sounds more like steady as she goes. A million homes in the last 5 years, a million in the next 5 years. These will go to those who can (or barely can) afford them. In the mean time the thousands who’ll never own their own home will still pay skyrocketing, unregulated rents. How is labor any better than the libs on this?

And where are these houses being built? COVID has changed the rules of the game around urban work and living. Many seek a more rural lifestyle but in many states we don’t have the transport or communications infrastructure to support decentralised communities, let alone the professional support base of teachers, doctors, nurses and aged care workers etc.

Will these programs address flood-and-fire ravaged zones?

Will we get continued build out of suburbs with uncertainties around fresh water supply etc?

How do our cities function without anchoring business areas or tax revenue from office blocks? ( Check this interesting Freakonomics podcast discussing these issues: https://freakonomics.com/podcast/the-unintended-consequences-of-working-from-home/ )

If all the houses to be built were public housing, would that be less inflationary, I would have thought so. The fact is that they can’t just not be built, not really discretionary.

Not only would it be far less inflationary overall but the savings in social costs, from health to welfare and even unemployment – hard to get a job when sleeping rough – would be orders of magnitude greater than the slight loss to consolidated revenue from bereft real estate touts.

This view, often repeated, ignores the role that “Supply” at all levels of the housing market plays in keeping up with demand – keeping prices in check – and allowing people to rent or buy under their own steam. There is absolutely need for more social housing, but the Government will never be able to build 200,000+ houses a year.

The “role that “Supply”…plays” is a furphy if the Location!Location! factor is ignored.

There is no shortage of housing per se in this country – it is where, and most importantly how, people choose to live which governs availability and thus price.

What rational function is served by megalopolises of 5M+ such as Sydney & Melbourne ?

In Europe, apart from London, Madrid & Paris – for historical reasons – there are none and very few over 1M yet Brisbane is 2.5M, Perth just over 2M and Adelaide <1.4M.

However there are many thousands of cities under 100K.

In the USA only NY at 8M is comparable, LA <4M, Houston & Chicago <3M but more than 300 under 1M.

It must be something to do with this country being so tiny and overpopulated…?

One point this analysis seems to overlook is the size of houses. Are we still building four bedroom McMansions, even though households are getting smaller?

Agree, demographic profile no longer fits well with traditional residential and/or urban design.

True, however it will not reduce the cost of them much as the main cost of houses is the land they sit on (and services connection).

There’s a simple, obvious first step.

Reduce immigration.

Not cease, reduce.

The gas lighting around solving the problem with new builds puts us back on familiar territory.

It’s the sort of behaviour we became accustomed to with the last mob.

Inequality rules-still.