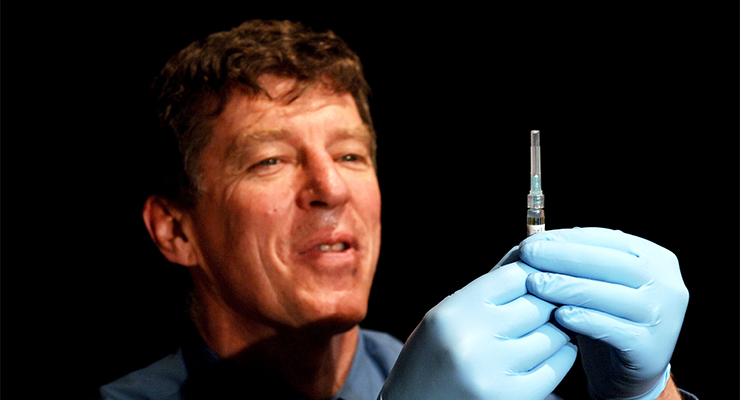

When Ian Frazer, one of Australia’s most celebrated scientists, retires next month, he will hang his white coat on a wall papered with the millions of lives his determination saved.

The former Australian of the Year has won almost every modern science prize on the planet for his co-discovery of the technology allowing the development of the cervical cancer vaccine, which annually saves almost 300,000 women. Indeed, his work with partner Dr Jian Zhou — which prompted a 16-year legal battle with American scientists who believed they had beaten the Australian duo to a vaccine — has almost eradicated cervical cancer in some countries. Australian children are protected with the free vaccine offered during high school.

But behind that glossy discovery lies a story Australia could learn from regarding how it grants science funding, how successes like Frazer’s can be used to encourage teenagers to study STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) and takes on challenges to cure everything from cancer to COVID.

On the way to success, Frazer fought with politicians, took out a second mortgage, and drove an old Mini with a broken front door. He worked out of an office the size of a broom cupboard, accepted the Australian of the Year title to raise funds, and donated out of his own pocket — all with the singular focus of advancing science.

He challenged former prime minister Tony Abbott to a bike ride so that he could plead for more money for science endeavours, and then made an appointment to quarrel with him when Abbott announced he wasn’t keen for his daughters to receive the cervical cancer vaccine.

Frazer disregarded former Queensland premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen and his conservative government which shut down conversation about HIV, AIDS and the gay community. His research revolved around the role of the human papillomavirus (HPV), requiring him to study men who had sex with other men. He visited gay clubs late at night to understand how underground the gay movement had become in response to how the public saw HIV/AIDS.

This was years before the final clincher when while working together Zhou showed Frazer the results of an experiment that meant they were able to carve a path forwards allowing the creation of a cervical cancer vaccine.

But here’s the thing — and something we need to learn about scientific research. A discovery in the lab means little unless it can carry a patent, be tested, grown into a commercial enterprise and delivered on a global scale.

And that’s what Frazer did.

Could we do that again? Probably not. Science funding for research, to answer the big questions, is limited. In part that’s because it takes a long time, longer than a single electoral cycle, and few governments want to commit beyond their next election speech.

The way we treat researchers and scientists in this country is appalling. The money is poor, and unless grants roll over, young talented researchers are frequently left without a job at the end of a year. But what happens to their work? How can we ensure we’re not discarding findings that might one day make the type of discovery that made Frazer a top scientist?

If Frazer and Zhou had stopped their research at the one-year mark, three-year mark or even seven-year mark, we might still be scrambling for the magic vaccine.

Years ago, I was asked to write Frazer’s biography. Understanding science, and how it works, was my biggest challenge. But what I found in early morning interviews and weekend chats was that Frazer the man is as inspirational as Frazer the scientist.

The donations he and wife Caroline make, particularly to the arts, are not highlighted anywhere. The fact he sits selling Lions Christmas cakes for charity each December is just what he does, along with Pilates, playing with grandchildren, navigating dangerous ski trails at breakneck speed, and winning best-dressed at parties.

During my research, I found he’d donated a large sum allowing the cervical cancer vaccine to be rolled out in a poor country. One question I asked reflected how his humility matched the calibre of his scientific work.

“What was behind your decision to do that?” I asked.

“Who told you that?” he shot back. “Why does that have to be in the book?”

Do you think funding for scientific research is not only important but vital? Let us know by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

Disclaimer: Madonna King is the author of a biography of Ian Frazer titled Ian Frazer: The Man Who Saved a Million Lives.

Ian Frazer is a great Australian and scientific leader. He has been commenting lately that his greatest legacy is in the students, the young scientists, and the work they will do in coming years. Sometimes we need reminding that true leadership is reflected in the achievements of others.

Absolute quality bloke and did outstanding work.

But so did his co-researcher, Jian Zhou, who deserves to be remembered.

He met Frazer in 1989 while they were in Cambridge and they collaborated for the next decade until Zhou’s death in 1999.

The world is a better place for his all too brief existence.

Makes me wonder how many great things didn’t happen. Thankfully this one did.

(And Abbott should not be on the same page as Ian Frazer.)

Nor should Barnaby Joyce who shared Abbott’s views about the use of the cervical cancer vaccine for his daughters.

My daughter was involved in the clinical trials of this vaccine. Frazer has my everlasting respect and gratitude. It is an absolute life-saver. The man is a hero, without question.