It’s better than nothing. I guess?

The RBA has issued a review of its behaviour during the pandemic, focussing on its bold decision to trick Australians into believing interest rates would not rise prior to 2024.

This was an unusual strategy at the time, and the risk didn’t pay off — the RBA started hiking rates before we’d got even halfway through 2022. Anyone who took the bank at its word and loaded up with debt is now cursing the masters of Martin Place.

“[The bank] could have done more to emphasise the conditionality of its statements about the future path of the cash rate,” reads the RBA review.

The apparent pledge not to lift rates until 2024 and the plan to fix the yield target until 2024 were linked — “Neither were well suited to respond to the unprecedented global events,” it admits.

It’s not a real apology, is it? But who is in the wrong? Us or them? Hairs can be split.

It is mostly true that the RBA expressed its arguments in a conditional fashion: if wages growth and inflation are low, we will leave rates at zero, and we believe wages growth and inflation will be low until 2024.

That is not quite the same as a promise. Calling it a promise is a simplification. But a simplification it encouraged.

Many journalists and insiders described the RBA as making a commitment at a certain time, not in a certain state of the world. I did. “It’s now talking 2024 for the timing of its next move in interest rates,” I wrote. Bernard Keane did also: “The RBA says not before 2024.” And The Wall Street Journal too:

And the chief economist of the Commonwealth Bank continually quoted RBA governor Philip Lowe as saying, “2024 at the earliest”.

If the RBA didn’t want these interpretations, it might have changed tack after misleading everyone. Instead, after these descriptions and headlines, it continued using the same sort of language.

The only conclusion you can draw is that it suited the bank’s purposes to have people believe this. The reason is simple: low interest rates encourage people to borrow and spend. If you promise interest rates will be low for a long time, the encouragement becomes stronger. That supported the economy, which was the goal.

Their message may have misled, but as the RBA says, it “helped shore up confidence during a period of significant uncertainty and disruption”. Which is true.

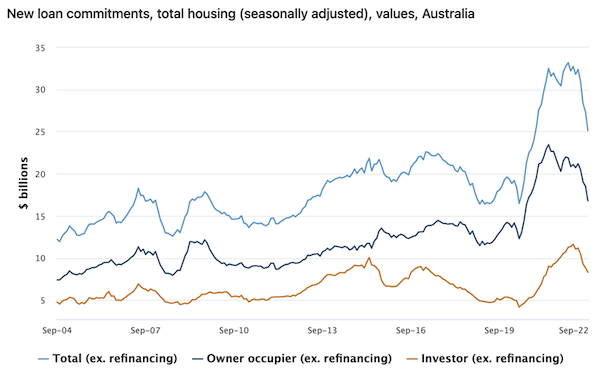

It is no surprise home loans were so popular during this period when rates were low and everyone thought they would stay low for years. As the next chart shows, home loan borrowing popped from $12 billion to more than $20 billion a month.

Incidentally, some of the people fooled by the RBA were lenders. They offered home loans at fixed rates for really long periods. You could get a three-year loan at a fixed 2% rate in 2021. Anyone who did that is insulated from rate rises for at least another year.

The banks are eating losses on a lot of their fixed-rate offerings, and I have scant sympathy there — it won’t affect their profits much (indeed, Commonwealth Bank seems to have increased its margins despite this phenomenon). I do feel for anyone who thought it was wiser to get a variable-rate loan in 2021.

The additional impost of the rate hikes we’ve seen so far is $700 a month on the average new 30-year owner-occupier loan in Australia. But in NSW, where average loans are larger, it’s a whopping $950 a month extra.

That’s a lot of household strain and pain. And many households aren’t even facing it yet.

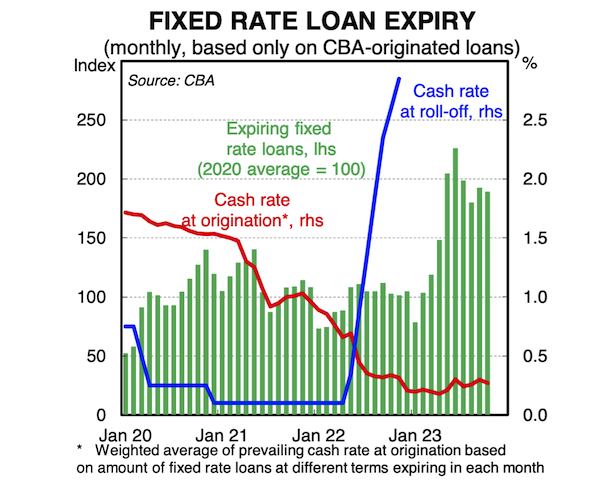

The green bars in the next chart show when fixed loans expire — lots of households will notice rate hikes for the first time next year. The red line tells you what the interest rate was when they started that fixed loan and the blue line tells you what it is when the fixed loan expires. Some of these borrowers are going to experience quite a shock.

These borrowers thought their fixed-term loan would expire in an environment of low interest rates, and perhaps thought they could start another fixed-term loan. Instead they will be in a world of hurt. They are the ones to whom the RBA should apologise.

Is the RBA’s mea culpa enough? Have sudden rate rises stung your mortgage? Let us know your thoughts by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

Given net present value assessments normally use use 3,5 & 7% as rates of return on large investments for sensitivity analysis, ie interest costs, I can’t imagine why anyone would take a spinmiester announcement about interest rates remaining at effectively zero for any length of time seriously.

I certainly didn’t take the RBA at its word. When my last fixed term expired in 2020 I refixed it for 5 years at 2.6% instead of 3 years at 2.1%. I figured that was still a good rate for the extra couple of years of certainty in budget planning.

Meh, buyer beware.

I seriously doubt any banks are basing their strategic analysis on what the RBA says.

If you look at things a different way it appears the RBA was not in fact encouraging the populace with statements about low interest rates. It was in fact dog whistling business & perhaps government, who also don’t want high interest rates (except the banks of course), to ensure they kept wages low.