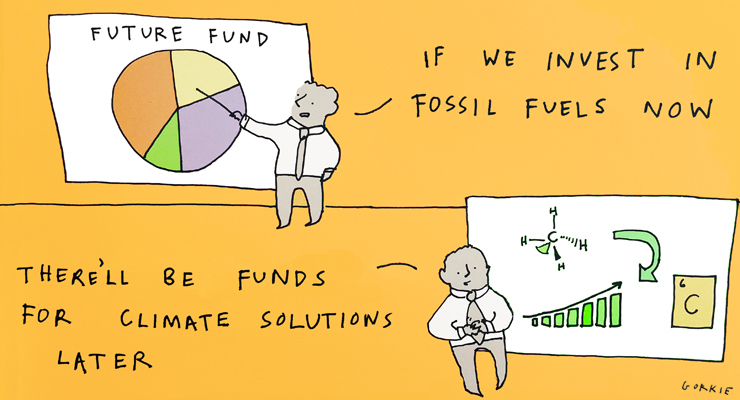

Earlier this week in The Australian Financial Review, Phil Coorey had an interesting little story about whether the government would order the Future Fund to lighten its investments in fossil fuels or “better align the fund’s investment strategy with the legislated goal of achieving net zero emissions by 2050”.

Behind the story is an interesting question: why does the government have to talk to the fund — which is independent of the government, correctly — about what investments it has? Why can’t it just look up the fund’s 2021-22 annual report, or its September quarter updates, to find out the investments of the fund?

It can’t. Nor can the media, or the public servant beneficiaries of the fund, nor investors in the fund — which is every single taxpayer. The Future Fund doesn’t identify individual investments.

It identifies areas or sectors, sure — for example 8.3% of its portfolio at September 30, or more than $16 billion, was invested in “Australian equities”, a further $25.5 billion in developed economy markets and $10.67 billion in emerging markets. There’s also $35 billion invested in private equity and $35.6 billion in “alternatives”.

But good luck finding which equities, which private companies. It is much easier to find out the Australian investments by the world’s biggest sovereign wealth fund — the gigantic Norges fund run by the Norwegian government — than the $241 billion of investments overseen by the Future Fund.

According to its December 2021 annual investment report, the Norges fund had investments in most of the 200 companies of the ASX 200, as well as some smaller companies, with US$1.3 billion invested in the Commonwealth Bank, just over US$1 billion in the ANZ, more than US$1.4 billion of CSL shares, more than US$600 million in Macquarie Group, over US$725 million in the National Australia Bank, US$739 million in Wesfarmers and US$691 million of Westpac shares.

Interestingly, the fund only owned US$186 million worth of BHP shares and US$421 million of Rio Tinto shares. BHP has sold its oil and gas assets to Woodside, but still has thermal coal in NSW.

When it comes to pure fossil fuel plays, Norges didn’t have any shares in Woodside, Santos or Whitehaven, nor Beach Energy, another oil and gas group partially controlled by Kerry Stokes’ Seven Group Holdings.

Not merely is it easier for us to find out what the Norwegians have invested in: fund managers with US$100 million or more invested in the US sharemarket have to provide four reports a year, 45 days after the end of the quarter. And like Australia, the US requires the holders of all stakes of 5% or more to be disclosed (10 days after the quarter in the US, three days in Australia).

So we can keep regularly updated on what some of the world’s biggest investors, like Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway and its A$454 billion treasure chest, have put money into. We know how many Apple shares Berkshire owns and how many Occidental Petroleum shares it bought in October and how many BYD shares it sold in Hong Kong this month.

But we don’t know if the Future Fund owns any Occidental, Apple or BYD shares, or Tesla or Twitter shares.

It’s an absurd lack of transparency in a fund that belongs to all of us, not to its chair Peter Costello, even if he did help set it up. The basic transparency that others take for granted, and which would allow debates on issues like whether we should be investing in fossil fuels, is wholly absent.

Which prompts the question — what, exactly, are taxpayers not being told?

yet another legacy of the Coalition’s pathological obsession with pointless secrecy (a disease being contracted by the current Labor administration also). We really need to enable a federal ICAC with teeth now and default public hearings..something that the pollies are in furious agreement about resisting!

Bravo!!! A journalist who does *not* say ‘begs the question’ when what he means is ‘invites the question.’ This is proper usage and it should be applauded whenever it occurs, because the proper use of the term is now so rare. ‘To beg the question’ is a useful phrase that means ‘to implicitly assume the very point at issue’. For instance, the following argument for God’s existence clearly begs the question.

Therefore, God exists.

The argument form is clearly valid: if the premises are true, so is the conclusion. But no one who doubts the conclusion would ever agree to the first premise. So the argument does nothing to resolve the question at hand: does God exist?

Question begging arguments in this correct sense occur all the time in public life. But thanks to the widespread misuse of the term, we now have no clear vocabulary in which to identify this error of reasoning.

And don’t get me started on the use of ‘refute’ to mean nothing more than ‘deny’! One does not, simply by denying an allegation, refute that allegation. It depends on whether your denial is buttressed by evidence that the allegation is in fact false.

Thanks 42. I’ve known the phrase’s usage was wrong – and it drives me crazy knowing that – but wasn’t sure why. Thanks for the easy explainer. It’s not about which question is being ‘overlooked’ (the common assumption) at all.

I think (I hope) that it’s not mere pedantry on my part. The misuse of ‘begs the question’ and ‘refute’ diminishes the expressive power of our language. Question begging is a serious and common fallacy. We have a phrase for it, but it’s been bent out of shape and no longer points to the thing that it should. If you give up and just let the careless journos have ‘begs the question’ and then try to use its standard philosophical alternative — petitio principii — that just leaves the ordinary punter mystified.

Well argued Bernard – the Australian addiction to secrecy is appalling, and also does not allow for independent scrutiny or debate about the best choice of fund allocations.

Future Fund also indulges in ‘cosplay’ pretending to be a ‘sovereign’ wealth fund, other days a superannuation fund (suggesting it should be the default); it’s merely to fund future defined benefit outlays for retired public servants vs. taking direct from budgets?

The thought that Peter Costello is in control of $241million of taxpayer’s money is simply terrifying.

Billion. Future fund. Whose future, exactly?