In the battle of the RBA v Australian bank accounts, the bank accounts look to be winning.

The Reserve Bank of Australia wants to crush spending in the Australian economy to try to drive down prices. But we’re just too comfortable. The latest data shows that, far from being skint, Aussies are still tucking away money in the bank and comfortable spending it. We have high savings, and they are getting higher.

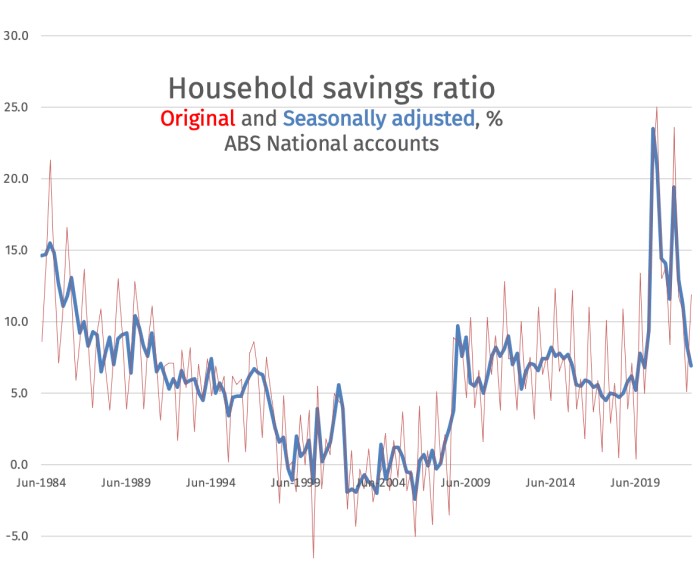

The savings ratio — the ratio of personal savings to disposable personal income — reported in the latest national accounts is still 6%. Not as high as the depths of the pandemic when we had nothing to spend on, but at the high end of what we’ve seen since 1990.

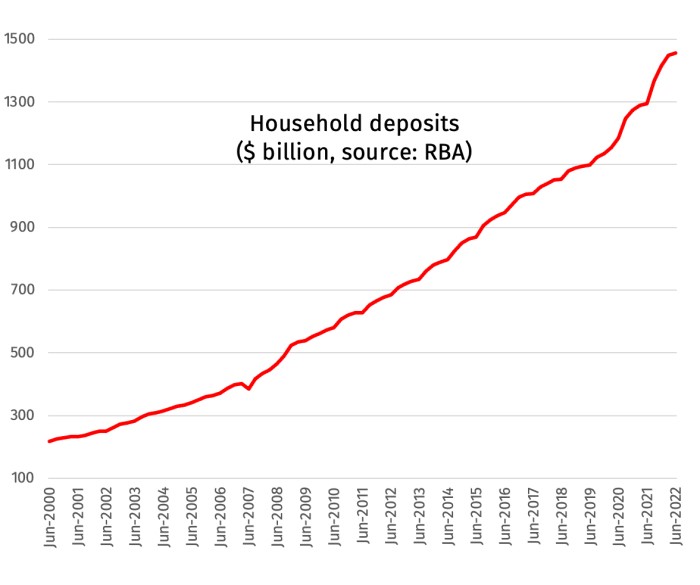

In 2020-21, we saved like never before. The amount of money in Aussie bank accounts is hard to grasp. As the next chart shows, we have squirrelled away nearly $1.5 trillion, or $58,000 for every human in Australia. And that’s just bank deposits — it doesn’t count business deposits, shares owned or superannuation. The figure rose enormously during the pandemic, up 32% since 2019.

But the average doesn’t capture the full reality. Older and richer people have more saved than younger, poorer people.

This enormous savings buffer means high prices don’t affect everyone the same. Who cares if broccoli is $12/kg when you’ve got $80,000 in cash in your spending account, right? So when the total stocks of savings are high, prices need to move even more to get people to stop spending.

Some families are borrowing to spend, while some are spending less than they earn. But more money is still being saved than borrowed.

Inflation should, in theory, push savings rates down. People don’t want to hang on to money when it’s losing its value every moment. You can see this most easily in times of hyperinflation when citizens try to spend their income the moment it arrives.

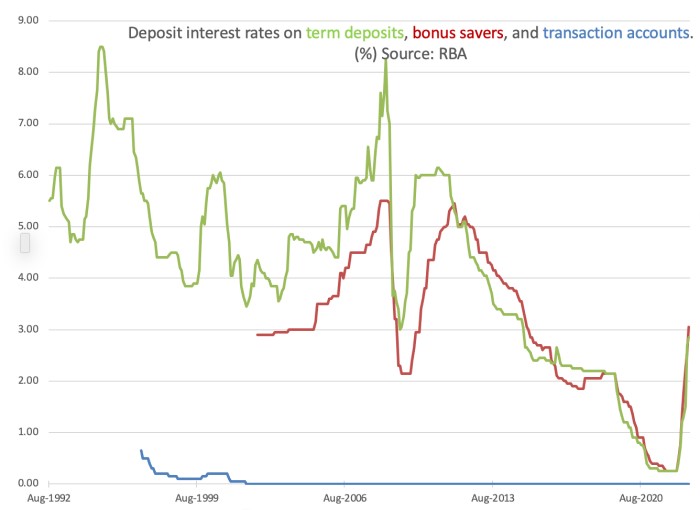

Higher interest rates should push savings up. The higher the reward for putting money in the bank, the more people will do it. This is one of the acknowledged mechanisms by which monetary policy works — putting money in the bank means it isn’t being spent nor enticing business owners to raise prices.

So how do these two effects net out?

The fact the savings ratio is falling says inflation is still winning. This acts as a warning to the RBA that it may need to further raise rates in 2023, even though it has hiked rates by 3 full percentage points in just half a year.

As you can see from the next chart, even though interest rates have risen a lot, they aren’t at historic highs. And they are nowhere near compensating for inflation, which is around 7%. Money in the bank is still losing its purchasing power every moment it sits there.

At the same time, though, banks are paying out more and more money in interest. As the next chart shows, they are pumping $20 billion in income into the pockets of depositors every quarter. And this data goes back only to the September quarter (July, August and September of 2022). Interest paid in the current quarter (October, November and December) will be even higher, thanks to much higher interest rates and higher deposits.

That income makes it easy to spend and makes the job of the RBA a little harder. Having to cool the economy immediately after the whole country stuffed their bank accounts to bursting point is a somewhat harder job than doing so when Australia was operating more hand to mouth.

The hope for anyone with money in the bank is the RBA can get inflation back down before the purchasing power of what they’ve saved evaporates completely. The magic of compounding works differently when real interest rates are negative.

I know this is a very simplistic calculation, but $20b/quarter (or $80b/yr) on $1.5tr in savings implies an (average?) interest rate of 5.3%

That seems very high.

The cost of Non discretionary goods is rising, fresh foods due to floods, energy and fuel due to war, rents due to a scarcity of housing and mortgage repayments due to the RBA. Excessive demand is not part of the equation yet we are using Monetary Policy to curb what exactly?

The RBA has a hammer and everything looks like a thumb.

Think one needs to compare with demographics of the permanent population when working age has passed the demographic sweet spot and median baby boomer has reached 67 years of age.

One would suggest there may be a linkage with the demographic fact of more retirees, and those transition, but breaking open superannuation pots whether modest with a pension, through to a full super account?

Just goes to show that nobody has a clue what is going on, and never did. Warren Buffet maybe.