The Chinese Communist Party’s strict zero-COVID era of continual testing, restrictions and harsh lockdowns is winding down. The ruling government body, the State Council, yesterday issued 10 new guidelines that include loosening restrictions, allowing home rather than public health quarantine, and largely scrapping the health QR code needed for entering most public places.

The CCP’s fearsome propaganda machine has also executed a neat backflip, shifting from its near-three-year characterisation of COVID as a potential Armageddon to one of more acceptance as a “weakening” virus.

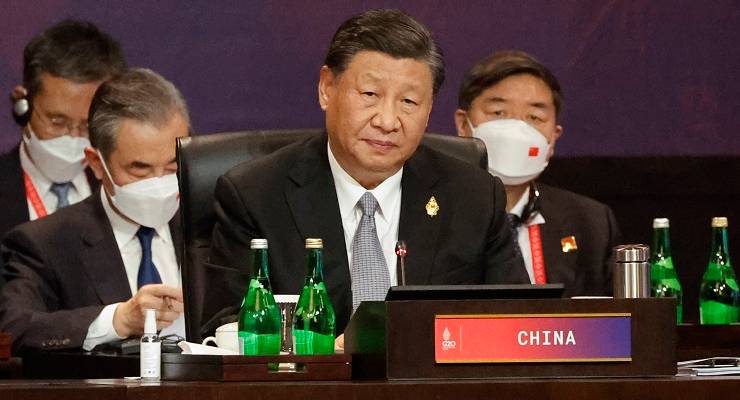

A week ago, small but unprecedented civilian protests had sprung up in major cities against China’s oppressive pandemic policies, which at times spilled into criticism of the party itself and its leader Xi Jinping. Some have posited that the overall tightening grip of China’s surveillance state was also a catalyst.

But as in other countries, loosening restrictions unlock potential dangers of coronavirus, with experts predicting fatality numbers could soar as high as 2 million.

This balance between health and freedom has created multiple tests for governments everywhere. However, for the Chinese government, which controls all aspects of politics and society, these tests are amplified — and under Xi, power and control have become increasingly centralised.

China’s civilian protests came at a time when there were signs the government was testing the loosening of its COVID regime at local levels. This was illustrated by rising case numbers in cities across the country for the first time in months, indicating that authorities were testing public patience for illness and disease in exchange for looser restrictions. Thus, any reasoning for loosening restrictions was unlikely to simply be related to the protests.

Xi may have brushed off this civilian unrest, telling European Council president Charles Michel in Beijing that they had been carried out by “frustrated teenagers”. Many, though not all, of the protests were university-based. Regardless, they will have deeply concerned the Chinese leadership — especially as Xi only a month prior secured a third term atop the party, underscoring his complete control over the organization.

It is clear that at least some of the frustration was due to economic management. The pandemic slowed down the Chinese economy, a lethargy already underway due to structural issues led by the country’s unsustainable property boom.

A wilting economy and the lockdown regime’s unsustainability are likely underpinning the government’s preparedness to swallow higher infections and fatalities. The protests have furnished it with an excuse. With youth unemployment already high and economic pain being felt across the nation, any further serious deterioration could create a situation difficult to control.

These factors loom as significant challenges for Xi and the CCP. The advent of the pandemic and the deep intervention of the state represent something of a fracturing of the social contract between the CCP and Chinese citizens. Control was accepted as long as the party delivered on increased prosperity and a safe society, compared with most other countries (provided one did not decide to challenge the state).

Another key problem for Beijing is that its decision to loosen zero-COVID restrictions could not come at a worse time of year. It is the start of the country’s harsh winter, especially in the north where temperatures tend to sit below zero — in some places, including Beijing, these sub-zero temperatures reach double digits. And as people huddle indoors, often in spaces with poor ventilation, viruses flourish.

China’s main holiday season, the January Lunar New Year, is also barely a month away from commencing. It is well known as the world’s largest annual migration, but has been put on hold for the past two years due to the pandemic. Hundreds of millions of Chinese people are internal migrant workers who spend most of the year working far away from home, sometimes many thousands of kilometres, and are predominantly from the rural inland working in factories on the eastern seaboard.

China’s public health system is nowhere near as comprehensive and robust as that of Australia’s, so the extent of any migration in the new year will place it under extreme strain. This exposes very real dangers for the nation, especially when combined with China’s weaker vaccines and its under-vaccinated population. The elderly will especially be at risk.

It is unclear what restrictions will be put on Lunar New Year; there are already local authorities trying to discourage travel in the face of booming air ticket sales. But it would be a brave government that tried to stop people from travelling in the face of the recent unrest.

Still, as in other countries, many remain fearful of the virus and do not even know about the protests due to the country’s tightly controlled media and internet. Chinese people are used to wearing masks and taking other preventive health measures, precisely because they know how frail the public health system can be.

In Xi’s latest term, his biggest challenges will be internal. The biggest risk externally is whether things get to a point where Beijing thinks an external distraction, such as a move on Taiwan, is needed to quell a restless polity.

How using the more neutral and correct abbreviation for Communist Party of China, CPC rather than CCP which is mostly used by China Haters? Always expect a biased negative China article when CCP is used.

CCP has been used for decades. What’s the reason for the change?

I’m no expert, but here’s my understanding.

CCP refers to the political party under Chairman Mao. The official title for the party changed to CPC some time in the 1970’s.

The structure and makeup of the party also changed greatly post 1970’s. It’s really quite complex.

But I guess the thing that annoys me is that these so called “China Experts” can’t even get the name right. So, so much for their expertise :-).

Maybe these “experts” mind set is stuck in the 1970’s ?

Not long ago – from the author =

OOOhhhh. Evil China. Lockdowns, more lockdowns, Blank A4 Paper. EVIL China.

And a short time later …

OOOOhhh. Evil China. They are letting the virus rip. Millions will die. EVIL China.

And the CCP / CPC thing is just a clear illustration of the authors ignorance (or worse).

Crikey – please – why are you publishing this drivel.

Seriously, the “China” topic is hugely important. Please find a knowledgable, informed, and unbiased contributor – PLEASE. I’m totaly sick of this rubish.

So far China appears to be leading the world in its pandemic response. Presumably China-bashers are proud of the way the US handled it; if so they’re on shaky ground. Chinese medicine famously dates back thousands of years, and they did build an entire hospital in two weeks at the beginning of the pandemic. (Or did I dream that?) Regardless of the opinions of people on the CIA payroll I see no looming threat to Xi’s control and position, unless some unforseen event suddenly arises. China likes stability, especially these days of much-reduced poverty. Reducing poverty is a goal some other countries could try. Worth a go.

Faced with an ailing public health system … China…

Is there any health system anywhere in the world that is not presently being described as failing or under great stress? The US has never had a public health system, the UK’s NHS seems to be completely falling apart, I see constant reports of Australia’s system being severely underfunded to the point of breakdown, now China’s system is ailing.

What is happening with the health systems in countries such as Canada, France, Germany, Italy? Is the model no longer suitable? I reckon we need quite a big discussion about this before it fails completely.