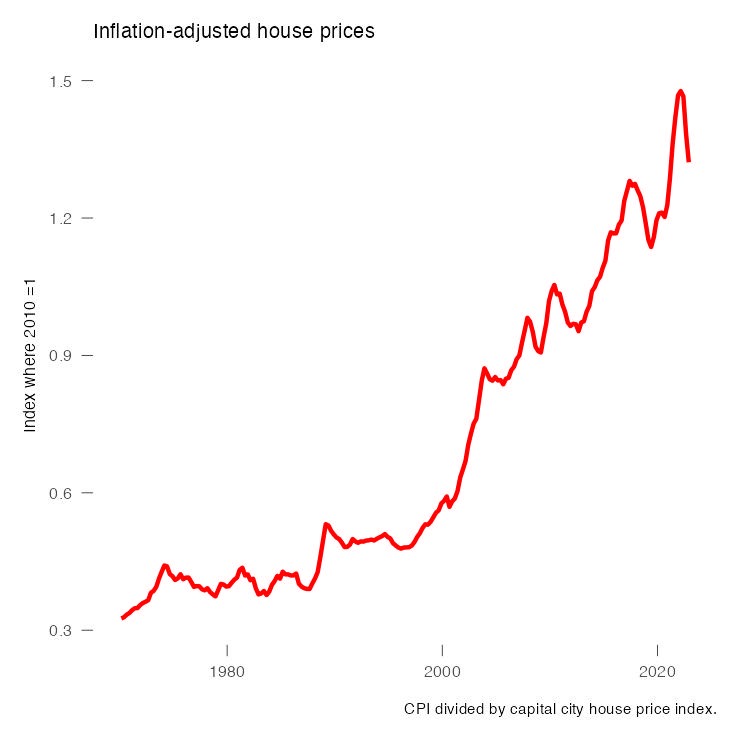

House prices are going one way just as every other price in the economy is going the other. This means that if you inflation-adjust house prices, they look even cheaper. House prices are down only about 5-10% in cash terms, but when inflation-adjusted, they are down far more — back to 2017 levels.

The next graph shows what I’m talking about. Inflation-adjusted house prices rose extremely sharply during the pandemic, pulling them out of the lull they fell into during the 2017-18 price correction. That sharp rise is being reversed again now, and if the forecasts of high inflation and falling high prices are correct, it has a way to go.

Does it make sense to inflation-adjust house prices? We often talk about inflation-adjusting wages. That makes sense because it allows us to find the buying power of wages too. We also inflation-adjust GDP, to see if it’s gone up in real (i.e. inflation-adjusted) terms or just nominal terms.

When we inflation-adjust house prices, what we’re really finding is the ratio of the price of housing to everything else in the economy. In recent years, housing has been getting more expensive than everything else.

These kinds of “exchange rates” can tell us a lot about our society. A famous example is the number of TVs we can buy with each boatload of iron ore we export, which helps explain how Australia has such a high standard of living despite not doing any real value-added manufacturing.

As RBA governor Glenn Stevens said in 2010: “Five years ago, a shipload of iron ore was worth about the same as about 2200 flat-screen television sets. Today it is worth about 22,000 flat-screen TV sets.”

Incidentally, iron ore costs less now than it did then. But so do TVs — we haven’t lost much buying power.

Relative prices are always changing. Chicken, clothing and TVs were once expensive. The number of chickens you had to forgo to get a house was once ludicrously low. You could buy a house for the price of 8000 chickens. Now it’s more than 60,000, as the next chart shows.

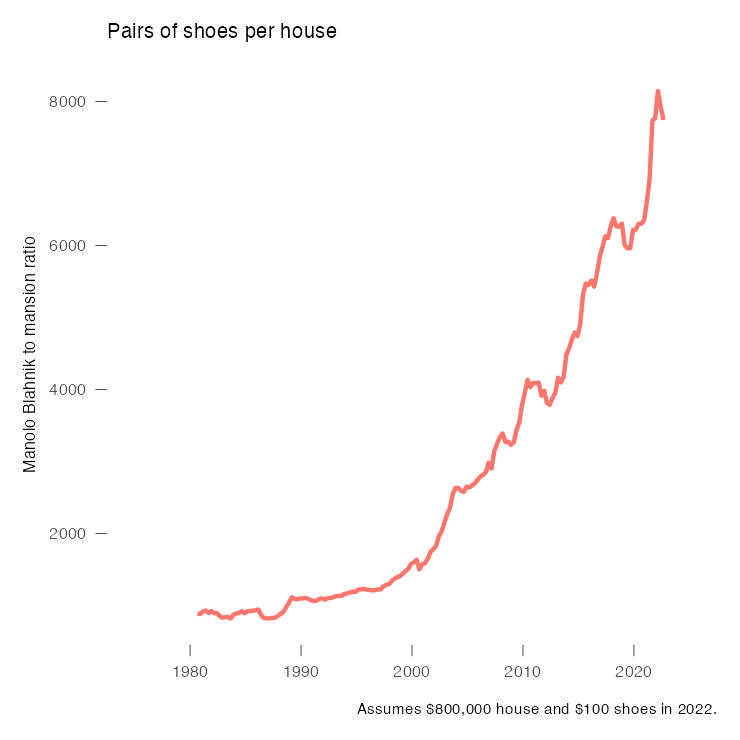

Same with shoes. A median house in a capital city once cost 900 pairs of women’s shoes. Now it’s 8000.

A house once cost as much as four cars, whereas now it’s 20 cars, etc, etc.

In all these cases, the cost of the consumer item has been suppressed by ever more efficient ways of manufacturing — mass production, automation, importing from places with low labour costs — while the price of land is being bid up and the price of the building on it is has a lot to do with local wages, which are rising.

In this sense, house prices are very high.

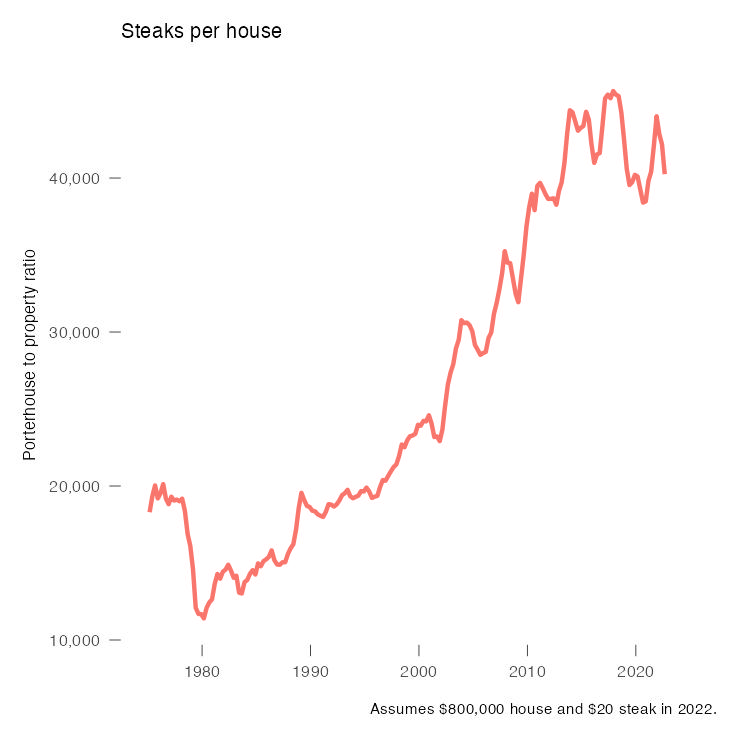

But the number of steaks you forgo when you buy a house hasn’t risen nearly so much, because beef has, like property, been soaring in price. In steak terms, housing is cheaper than it was in 2010 and has merely doubled since the 1970s.

I’d hypothesise that mortgage holders are roasting a lot more chicken than beef these days, compared with the 1970s.

Where are house prices heading?

House prices and inflation: do they usually go in opposite directions?

There’s two reasons to think they would:

- People devote as much as they can to their house purchase. But they do need to eat. If prices of food and petrol go up, people have less left over to spend on their house. In this story, it’s the relentlessly low inflation on food, clothing, etc, that has helped drive up house prices over the past couple of decades. We can meet our basic needs with less and less of our pay, meaning there’s more to put towards the house.

- When inflation is low, interest rates are low, and when interest rates are low, people can borrow more to buy a house.

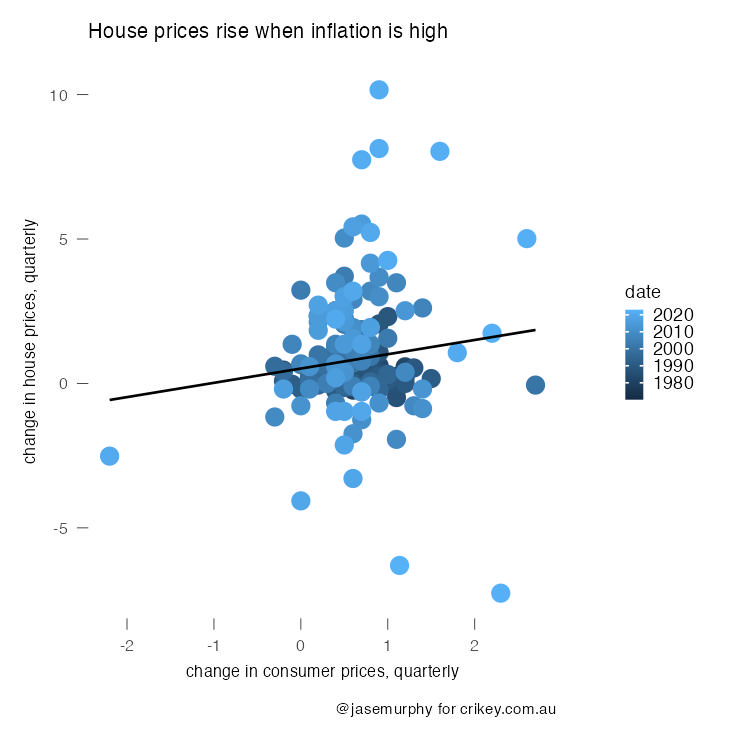

The data tells us the opposite. As the next chart shows, historically we see that when inflation is high, house prices are rising fast too.

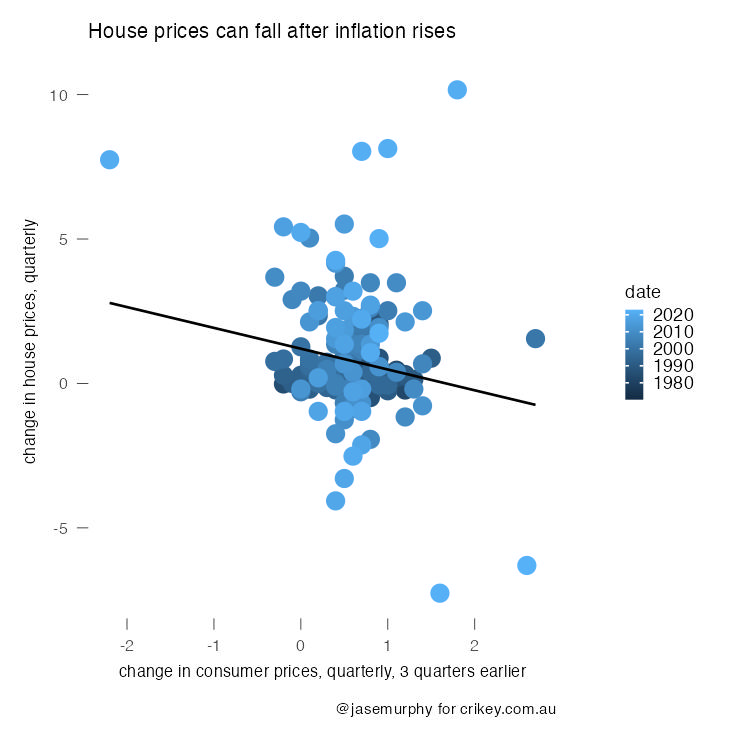

What’s going on here? Could the effect be delayed? If we timeshift things and see how house prices react nine months after a period of high inflation, we start to see a negative reaction.

The data shows only 3% of the variation in the change of house prices is explained by inflation nine months earlier, so it’s not a tight correlation, but there’s some effect.

The big reason inflation causes house prices to fall is that the central bank reacts. First inflation rises, then the bank hikes interest rates, then house prices fall. It’s notable that if you timeshift the correlation even further, it disappears — beyond a year after a quarter of high inflation, there’s no correlation with falling house prices. This could suggest that Australian house prices will stop falling once inflation is back under control, stabilising and then growing again.

After all, while chickens grow in battery cages and land is in fixed supply, the number of chickens you have to forgo to buy a house is unlikely to keep plummeting forever!

In looking at that house prices against inflation graph, keep in mind that inflation is grossly understated, because it does not capture skyrocketing house prices.

30 years ago, outside of Sydney and Melbourne (and 40 years ago including Melbourne), median house prices ran quite affordably at <=3x median full-time wage.

Median full-time wage today runs at something like $80k…

Check out the “18.6-year property cycle” to find out why house prices are going to continue to soar for the next three or four years.

The cycle you refer to has become an article of faith. The sheep-like followers themselves may make it a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy in some countries. But if it were to apply here, as you imply, there would have to have been a four year ‘bust’ just after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. But there wasn’t, and hasn’t been one of that duration since the 1940s.

18.6 years ? House prices have been soaring for the last three for four _decades_.

That’s only nominal headline price not real value inc. CPI and all costs; ‘time value of money’.

30-40 years ago a typical house pretty much anywhere except Sydney and parts of Melbourne cost 2-4x a typical household income.

Now, a typical house costs 6-10x a typical household income *and* household incomes are higher because more of them are dual-income, and dual-full-time income.

Ie: more people have to work a lot longer to buy a house.

House prices are completely out of control, have been for decades, and it is destroying everything.

Makes me want to leave the country again. Like so many others no doubt

Is cost of housing included in the inflation calculation? Should it be?

And shouldn’t the measure be house prices vs income?

CPI basket includes new dwelling owner-occupier sales, rent and bigger renos. It fluctuates as a percentage of total ownsales, but think it’s pretty modest, in the teens.

It’s quite hard to nail down, actually. Maybe someone more expert can enlighten me but I can see zero reason to quarantine existing dwellings sales, and many not to. Unless you’re a Housing Sector parasite/Ponzi grifter in some capacity, perhaps. Because…well, existing dwelling sales tends to be where the Ponzi Grift is at its most most grifty, isn’t it. In established desirable suburbs where people want a home big enough to have a family, without having to commute for hours. New dwellings do tend to be relatively shielded from the worst of the Ponzi oops sorry I mean ‘inflationary’ pressures, by a raft of contractual, time-practical, construction and financing realities.

Maybe my long-nurtured hunger to see the repulsive Australian speculative property market collapse has got the better of me. Maybe there’s a perfectly logical reason to not include all owner-occupier sales in CPI markets. Anyone?

markers

Also, CPI doesn’t include the land component, which – until the COVID supply chain problems – is where almost also of the bubble had come from. It also means that the amenity loss of shrinking blocks isn’t accounted for. Eg: whereas ~20-30+ years ago even an average house would be on a 1200/800/600 section (depending on where you live), these days anything above 400-500 is ‘big’, even out in the digglies. So not only is CPI not accounting for one of the largest components of buying a house, but it’s also not accounting for the steadily declining size of the that component despite it’s increasing price.

And while houses have gotten bigger, it’s true, a lot of that has come from attached double garages replacing traditional carports. Further, building quality has declined from exceedingly average to mostly poor (something else poorly/not at all capture in CPI). Without good and specific knowledge of its history, you’d be brave to buy a house built in the last 15-20 years, and absolutely out of your tree to buy an apartment, especially in any of the major bubble areas (Capitals, tree- and sea-change areas, etc).

From: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/frequently-asked-questions-faqs-about-measurement-housing-consumer-price-index-cpi-and-selected-living-cost-indexes-slcis

While you’re right about apartments, free standing dwellings are better than they were, except orientation to the sun ,natural siting advantages, the message has been lost in despatches.. space outdoors as you state , doesn’t even factor , the environment can go jump, developer mentality. The thought must be that screens are more important, Leunig does that cartoon.

They certainly aren’t dropping in regional areas with all the city slickers fleeing the abodes for the ‘cheaper’ regional property only to drive the prices through the roof for both buying and selling and turfing longstanding locals onto the kerbs or into a car.

An unintended effect of the extended lockdowns in cities especially Melbourne.

An over-use of the word plummet. Minor correction, is all. Prices could halve – and we would all be richer. What would we do with the money saved? Buy a bigger house of course. You’d be silly not to. It’s tax free, which is why they’re so expensive.