Australia’s exporters are enjoying an impressive upswing after a few relatively subdued years. Cotton exports over the past five months, June to October, averaged a record $674 million per month, almost three times the value over the same period last year. That’s despite lower prices.

Oil seeds and fruit extract exports surged to a record $400 million per month, more than three times last year’s revenue. Dairy product exports increased 28%, animal feed 40%, raw cereals 60%, and wheat a thumping 73%.

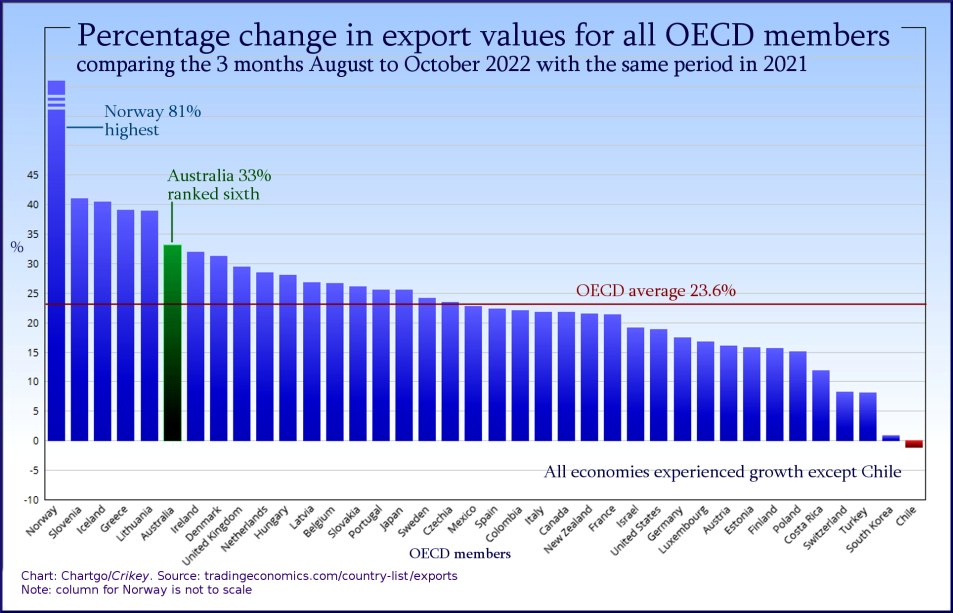

This puts Australia back among the global leaders, based on year-on-year export growth. In fact, of all 38 members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Australia’s exporters enjoyed the best gain in October compared with the previous year.

Monthly outcomes bounce around, however, so we should consider several months for valid comparisons. When we do, Australia currently ranks sixth in the OECD:

Export expansion

Trade Minister Don Farrell has focused particularly on rebuilding regional trade. Exports to South Korea over the past five months, June to October, reached new records, averaging $4.5 billion per month. That’s 41% higher than the same period a year earlier and two and a half times the year before. Exports to India over the same period averaged a record $2.3 billion per month, up 33% from the previous year. Exports to Indonesia are up 45%, nearly quadruple the year before.

Economic growth

Exports are one element in Australia’s return to strong gross domestic product (GDP) growth in recent months. Quarterly growth in the September quarter was 0.65% and annual growth was 5.87%.

Australia ranked fourth in the OECD on annual growth for the 2022 third quarter. This is not quite as impressive as ranking first, achieved in 2009 during the global financial crisis (GFC), but it is vastly better than ranking 22nd, as in the recent June quarter, or 30th a year ago:

Employment progress

The unemployment rate fell below 3.5% in July last year for the first time since data collection began in 1978. It was below that level also in October and November.

Regarding unemployment, Australia now ranks a creditable eighth among OECD countries, the best ranking since 2013. The OECD average is currently 5.69%, the lowest on record. Australia’s underemployment rate fell to 5.8% in November, the lowest level since mid-2008, before the onset of the GFC.

Job participation has crept up to 66.8% in November, from below 65% a year earlier and as low as 62.6% in early 2020. Although conventional wisdom considers higher to be better, this is not always true. Keeping students on at college instead of being forced by poverty into the workforce and allowing workers older than 80 to retire are desirable outcomes, each of which reduces job participation. There is an argument that the optimum participation rate in Australia is between 64 and 66.

The percentage of workers aged 65 and over still working hit an all-time high of 15.34% in November.

Budget progress

Early indications are that the Albanese administration should achieve a substantially lower budget deficit than the $36.9 billion budgeted in October. By the end of November, income tax receipts were $3.9 billion higher than projected to that point, and total receipts were up by $6.6 billion. Outlays were $1.2 billion below budget, yielding a net position improvement of $7.8 billion, after five months.

Gross debt was projected to deepen from $895.3 billion in June 2022 to $927.0 billion by June this year. So far, five months into the fiscal year, gross debt has been reduced to $891.6 billion.

Other critical variables

Inflation over the year to October was 6.9%. While that’s comparatively high, this is a global challenge. Australia ranks 10th in the OECD, whose average is a troubling 12.4%.

Australia is travelling satisfactorily but not brilliantly on productivity, living standards, interest rates and wealth distribution. Business profits are still surging.

Challenges ahead

Wage levels are not keeping pace with inflation. The latest data shows total wages rose 3.6% over the year to November. That is poor given Australia’s enormous wealth, booming corporate profits and ever-rising national income.

The Albanese government has also made a slow start with housing availability and affordability. Public housing approvals over the five months from June to October last year came to just 1329, historically exceedingly low.

The Rudd/Gillard government built an average of 2368 in the equivalent five-month periods in each of its six years. The Hawke/Keating government built more than 5000 in the same periods in its first six years.

And while this analysis affirms exporters, there is room for considerable improvement, as shown by Australia’s exports to GDP. The average of the past three years, 2019 to 2021, is 23.4%. That is historically high for Australia, but ranks a dismal 35th among the 38 developed economies. The OECD average is 54.5%, with only Japan, Colombia and the USA faring worse than Australia. The Netherlands, Ireland, Belgium, Hong Kong, Singapore and others are above 80%.

It is still early days, but the new economic management appears to be on track.

Why quote national economic growth? It’s lame when driven by population increase and everyone knows it.

It’s GDP per capita or give it a miss altogether.

Where is the evidence of correlation/causation between population & GDP vs. ‘everyone knows it’?

If so, what’s the issue with ‘growth’ when a nation can have growth and falling emissions?

Like others, one’s ‘growth’ can be given back whether growth in career income, property gains etc. and then you don’t need to worry about ‘growth’?

Couldn’t agree more. We have the dumb approach to GDP growth. Always have. If it is GDP per capita we are measuring, then we have reached recession several times over the past 20 years.

But our exports are still mainly energy and primary produce, more typical of a third world country.

So true.

Huge elephant in the room here surely, no mention of climate destroying mega exports of coal and gas? This article perpetuates the dangerous illusion that growth is unconditionally good. And why is it not shareable Crikey?

No, more data is coming out from nations showing no linkage between increasing economic growth and declining emissions?

See FT: ‘Economics may take us to net zero all on its own. The plummeting cost of low-carbon energy has already allowed many countries to decouple economic growth from emissions.‘ 23 Sep ’22 John Burn-Murdoch

Why is such evidence ignored in Australia, a threat to the hegemony of fossil fuels?

No, more data is coming out from nations showing no linkage between increasing economic growth and declining emissions?

This is also true. We, i.e., I mean Oz, is resource rich. It follows that if countries can pay for the and are less developed along the renewable energy path, then we stand to benefit from the sale of said resources. Mainly Gas and thermal coal.

Interesting analysis, but one would expect to see service exports to increase significantly with China opening up, then previously international education and working holiday backpackers returning?

The latter two cohorts known are known as ‘net financial budget contributors’, it’s not just university but the English language sector & VET (vocational inc. TAFE) that flies under the radar as most <12/16+ months, hence, not included in the NOM net overseas migration.

One of the potentially significant issues for Australia, especially compared to Europe which is now catching up on immigration esp. net migration, is ageing population tugging on budgets versus decline in working age due to low fertility i.e. passed the ‘demographic sweet spot’ pre Covid (OECD); backgrounded by demands for immigration etc. restrictions.

This latter working age cohort is peak private/personal spending, investment and (PAYE) tax paying to support budgets for more retirees who spend/invest less, but are becoming more significant as the ‘baby boomer bubble’ transitions to retirement.

retirees who spend/invest less

Self funded retirees spend differently, not necessarily less. In our working years as PAYE mugs we spend on mortgages, superannuation, children, commuting and alimony. It’s perverse that in old age we typically have more disposable income to spend on travel and health care. And still income tax of course.

Of course, but you are speaking of the past, neither now or the future? Dynamics change and especially demographics which impact tax, budgets and retirement income.

For now (esp. fully) self funded retirees are a minority versus full or part pensions and related: 77 per cent of Australians over the age of 65 receive income support…13 per cent of Australians are over 65 years now, growing to 25 per cent by 2047 (DSS).

Further, most retirees whether they can afford to or not, are hardly likely to be buying a house to live in on a mortgage, running a young family, working full time and paying related costs.