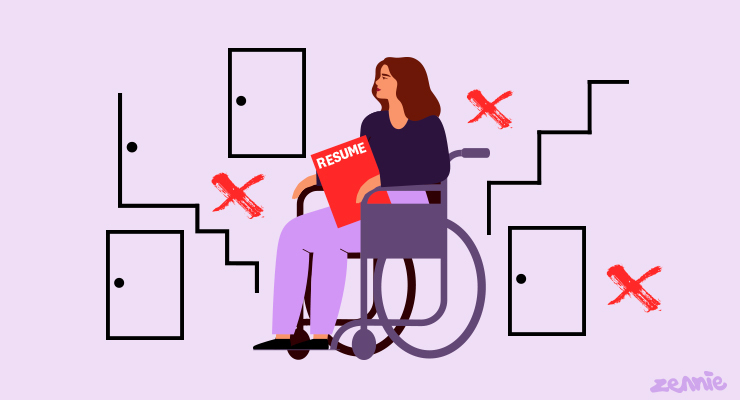

Every few years there is newfound enthusiasm for the employment of disabled people. The huge gap in work rates is exclaimed over, and a round of consultation and pilot programs are announced. Disabled people say the same things, again, and are ignored, again — and the barriers excluding us from work remain.

Despite the billions spent on disability employment services, mostly staffed by non-disabled people, disability employment rates haven’t changed in 30 years. The most recent ABS data shows 53% of disabled people of working age are in work, compared with 84% of our non-disabled peers.

The more severe a person’s disability, the less likely they are to be employed, with only 25% of people with a severe or profound disability in the labour force. Of people with an intellectual disability, 32% are in work, many earning sub-minimum wages in sheltered workshops, also known as Australian disability enterprises.

The federal government is no exception to this enthusiasm, announcing pilot programs and reviews and consultations. The previous government also enthusiastically consulted during its last term, having introduced Employ My Ability (a disability employment strategy), an NDIS employment strategy, a public service disability employment strategy, an employment-targeted action plan as part of Australia’s disability strategy, funded the IncludeAbility program at the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC), and did 18 months of working groups and consultation about the disability employment system.

This endless consultation results in similar findings: disabled people can’t get a job due to discrimination and bias, lack of accessibility, and systems working as barriers to support.

Discrimination at work

Of course, not all disabled people can work or want to, but for those of us that do, it is time to get serious about what obstacles are preventing us from employment, starting with one of the biggest: discrimination.

Not a cent of funding for disability employment service (DES) providers goes towards tackling discrimination, including that taking place within DES providers.

Back in 2016, the AHRC Willing To Work inquiry said:

Employment discrimination against people with disability is ongoing and systemic. At the recruitment stage, bias, inaccessibility and exclusion are recurring issues.

Every disabled person I know, including myself, has experienced discrimination at work or while trying to get a job. Discrimination at work is when the workplace isn’t accessible or when the adjustments disabled people need are refused. Adjustments can be physical access to the building, an accessible toilet, noise-cancelling headphones, screenreaders, captions for video meetings, more time to do tasks, part-time work, working from home, written instructions, Easy Read material, Auslan interpreters and changes in duties.

But discrimination also means intrusive questions from colleagues, not being given the same opportunities as other staff, being refused senior work despite having the relevant skills and qualifications, being bullied and targeted, and being exposed to a work environment full of ableist language and attitudes.

Complaints to the AHRC from disabled people about discrimination at work continue to increase, and these are just the few complaints that actually make it to the commission. Most of the time, we just leave our jobs and try to find a more accommodating workplace.

Tackling rampant discrimination against disabled people at work doesn’t feature much in any federal government strategies and pilot programs, apart from some hand waving at “employer confidence” as though they are our bashful suitors. This is despite research that finds “it is apparent that employers, co-workers and third-party organisations (e.g. insurance companies) directly or indirectly treat people unfairly, or, in the worst cases, display open hostility to Australians with a disability”.

Real solutions

So how do we address this situation? A good start would be to fix the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) so there are consequences when we are discriminated against at work. Currently, the law itself is broken, making it almost impossible to prove discrimination based on disability, and taking action under the DDA can mean disabled people wear the costs. The DDA also needs altering so the AHRC can take action on systemic discrimination, not just on individual cases.

Another step would be to reform the $1.4 billion a year that the disability employment service (DES) system receives to tackle discrimination. Most DES providers don’t employ disabled people themselves, so requiring a minimum number of disabled staff would bring expertise about stopping discrimination within organisations. DES providers could also have a role working with local employers, linking them with disabled people and the support they may need to do their jobs.

Ending discrimination against disabled people at work is essential if we are to find and retain employment. Ignoring discrimination means nothing will change.

Thank you El. If only the organisations working with disabled people could model best practice in employment and the workplace, providing the rest of us with a guiding light. This could start with Disability Employment Services providers and the NDIA.

Even low hanging fruit, like dubious requirements to have a driver’s license , isn’t tackled by current systems. Regrettably, even NGOs and public services that are run for PWDs sometimes engage in this indirect discrimination. It is an inherent requirement for some positions, but not for all the ones advertised requiring a license.

What are the employment stats for disabled people in the various public services in this country. That would give us an idea of whether the government walks the talk or just talks.