A staggering sell-off of the stocks of Indian conglomerate Adani Group was sparked in late January by a report released by Hindenburg Research that raised questions about the group’s debt levels and use of tax havens. The Adani Group’s stocks declined more than 50% in the aftermath of the report’s publication, and those declines have had a massive effect on the wealth of the company’s namesake, Gautam Adani, who had previously been the world’s third-richest person and Asia’s richest overall.

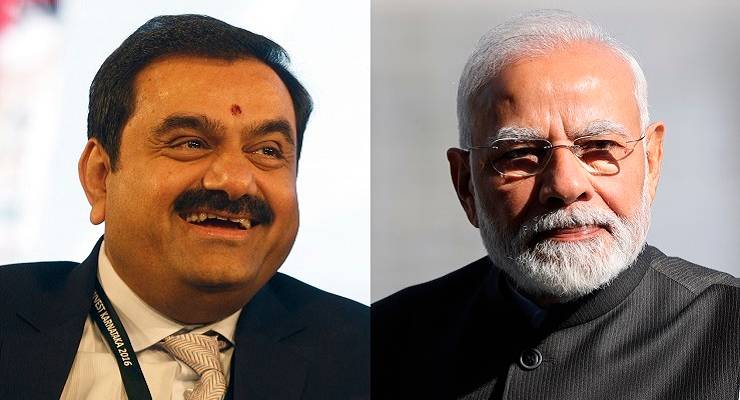

The Adani Group has denied the allegations, saying they have “no basis”. But the controversy has focused attention on the group’s central role in the Indian economy and its founder’s close relationship with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

What accounts for Adani’s rise in the first place? What is the basis for his close relationship with Modi? And what role does the Adani Group play in the Indian economy? Those are a few of the questions that came up in my recent conversation with Foreign Policy economics columnist Adam Tooze on the podcast we co-host, Ones and Tooze. What follows is an excerpt, edited for length and clarity.

Cameron Abadi: Adani has a pretty impressive rags-to-riches story. What were the key turning points on his path to great wealth?

Adam Tooze: It’s a fascinating story. He’s born in 1962, as India’s demographic boom is cresting. And not in a poor family by any means but to a small businessman, a small trading family. He initially embarked on an undistinguished career in school and then headed to commercial college but then dropped out. And in 1978, he entered the diamond trade, which is large in the province of Gujarat, and then sets himself up as a sort of export-import trader.

From the ‘90s onwards, he embarks on the infrastructure projects — management of ports, the construction of railway systems — which will make him famous, indeed legendary. So it’s the story not really of a kind of business genius who has some technological, gee-whiz idea that conquers the world. It isn’t a story of the magnificent technical excellence of Indian IT services, for instance. It’s a more classic story of the accumulation of capital by means of trade, trading on margins, basically, and then a shift into infrastructure.

This is where the key element in the Adani story comes in, which is politics and the politics of connections and clientelism. And that’s really the decisive moment in his career where, you know, after the ghastly pogroms against the Muslim population of Gujarat in 2002, when Modi is under massive pressure, Adani solidarises himself with Modi against, at the time, the prevailing mood of Indian business opinion. He in fact breaks ranks and forms his own industrial association, or business association, and on that basis really forms this lasting connection to Modi that is really the distinguishing feature of his business enterprise.

And that’s what has enabled this utterly explosive growth. I mean, this was a still moderately sized business in the ‘90s and the early 2000s, which has now become absolutely a globally scaled enterprise and the foundation for huge wealth for Adani and his family.

CA: What exactly links Adani and Modi’s [Bharatiya Janata Party] BJP party on an ideological level? Do they share a vision for what kind of country India should be? Or is this relationship an expression of a kind of material division of labor — Adani as the economic arm of the Indian state under the BJP in service of further economic development?

AT: I think the key phrase is nation-building — both words in that hyphenated term. So national projects aiming for truly comprehensive scale, which — when you’re dealing with a subcontinental state like India with a population that India has — is a gigantic undertaking.

So for the Adani Group to establish itself the way it has as the key power producer in the private sector, absolutely key player in port infrastructure on the national scale, and absolutely key player in airports — air mobility being key in a country the size of India — now moving into a new position in cement, this is creating a national economy out of the relatively decentralised provincial structures, which until a remarkably recent date dominated the Indian economy.

And for the second element — the building part of nation-building — delivery is the absolutely key thing because if there’s one problem the Indian state machine has, it is the capacity to deliver. They have a chronic problem. There is no shortage of brilliant minds that can conceive of wonderful plans but actually implementing policy down to the village level and across the entirety of this vast country, that’s a huge challenge.

And I think it’s the combination of those two elements that really has forged the almost mythic relationship between Modi on the one hand and these two big business groups: [Indian businessman Mukesh] Ambani on the one hand and Adani on the other — both from Gujarat. And I think that’s another element that you could say was also a kind of ideological narrative, which is the talk of the Gujarat model.

To put it crudely, you might say it was a sort of Indian Thatcherism or an Indian neoliberalism. It was a break, as in the case of [former British Prime Minister Margaret] Thatcher, driven from within the government machine, in this case in the province of Gujarat, against the rather top-down, state-directed model inherited from the Nehruvian period of early independence, the 1940s to 1950s, where India toyed with socialist, social-democratic planning models. And this is replaced in the ‘90s and the 2000s by this Gujarat model, which is a kind of open embrace of a productive powerhouse relationship between big business interests and government.

CA: Could you summarise the allegations against Adani from Hindenburg Research — and what does this episode reveals about the role played by short sellers like Hindenburg Research in the global capitalist economy?

AT: First, we can’t stress strongly enough, the Adani Group vigorously disputes the allegations. But the allegation is that through a network of essentially family-linked holding companies held to a considerable extent outside India, the Adani Group dramatically inflated the value of its stock. So around about 75% of Adani shares are held by other businesses, according to Hindenburg Group, which are in a sense simply postbox entities situated in offshore places like Mauritius, for instance, which drive up the stock value of the Adani Group.

The significance of that is not only that it brings paper gains for the holdings of the key members of the family, but much more importantly, what it enables them to do is to leverage those high stock values, to get bank loans and to get credit, which then turns into real purchasing power with which you can then launch large investment projects, buy out rivals, and actually reshape India’s political economy.

Now the Hindenburg group in pursuing this case is, in a sense, involved in playing a game in India that it has played elsewhere. They’re an interesting, very small research outfit that specialises in doing — I’m not sure I would call them regulators. It’s a little bit more like private investigator kind of work. They seize on a cause. They then decide that a company is massively overvalued. They do their homework. They then take short positions and through the force of their research attempt, as it were, to drive the value of the firm down, which generates large profits on their short positions.

The sophisticated Indian response, I think, is that there’s really an element of culture clash here. There aren’t many players in the Indian financial markets who imagine that the value of the Adani Group is determined in a conventionally free and fair way because people aren’t naive about the way in which India’s political economy operates. And so the sophisticated rationale for what’s going on in India is that Indian financial investors know that this is part of the Adani Group’s business plan. And with the backing that they enjoy in political circles, they are not just too big to fail but essentially identified with the Modi-ite project. So long as that is hegemonic in Indian politics, these businesses cannot fail. So there is in fact very little risk that you won’t get paid back. And to that extent, no harm, no foul.

But what actually is happening is that India’s economy is becoming progressively more and more distorted by this self-sustaining linkage between high market valuations, large credit, and deep political connections constituting a too-big-to-fail kind of juggernaut that can’t be stopped. And the negative consequence of that is not in terms of an investor protection case — if you’re on this train, you’re probably going to be fine. The real issue is what it does to the Indian economy and what it does, by implication, also to Indian society.

CA: What does Adani reveal about the role of the super wealthy in countries at India’s stage of development? Does Adani act as an engine of domestic development through reinvestments in the country or through philanthropy? Or is it instead that he takes his money out of the country and insulates himself from the Indian economy?

AT: What’s really interesting is that this is not, I think, as far as we’re able to assess anyway, a Russian-style model. I mean, this is an immensely wealthy family. They will have property in many parts of the world. But this is not a model like the Russian oligarch one, where you pump oil and gas in Russia, you sell it for dollars, and then you stash those dollars in a Swiss bank account. That is the kind of classic model of truly offshore oligarchic finance that is draining resources from a country. And as far as we’re able to assess, the Adani Group is using offshore money to sustain and double down on their positions in India. The purpose is to raise more credit so as to be able to do more investment in India. So this is not an instance, I think, of a group that is operating primarily in an extractive mode.

The Adanis have also become very heavily involved in philanthropy. For the occasion of Gautam’s 60th birthday, they launched one of the largest philanthropic initiatives that India has seen since the glory days of the Tata family. They pledged $7.7 billion in 2022 — so very considerable amounts of money in the kind of league of [billionaire] Bill Gates at that stage.

CA: What does Adani’s career and his wealth tell us about the Indian economy in general? I mean, what kind of capitalist country is India exactly?

AT: If you go to Delhi and you speak to economists, that’s the question that preoccupies them. And the upside story, the one that the proponents of this system favor, is that it’s a South Korean-style, chaebol-type system where you have these very, very powerful conglomerate families like the Samsung Group. So that’s the most favorable vision, that these powerhouse private, public-private partnerships will be the drivers of an Indian industrial development or modernisation like that of South Korea.

And on the darker end of the spectrum, the fear is that you could see the development of a crony capitalism that shifts ever more towards the more ominous sort of Russian development where you have quite fundamental erosion of the rule of law. The real worry, I think, is that you could see a much more fundamental degeneration of competition, of civil society control, and that is why many people regard the acquisitions by these big groups in the media space as being so worrying because one of the consequences of that is that freedom of speech is increasingly curtailed and even tenure in universities becomes problematic.

But setting all of these big sort of historical analogies aside, ultimately, the rationale and the acid test of this system will be what political scientists call output legitimacy. Can they get the job done? Are they actually going to be able to deliver on a raft of big infrastructural projects that India needs over the next decades — notably, for instance, in the renewable energy and the sustainable energy space? In the end, these corporate stories have to translate into the infrastructure that enables that more broadly based macroeconomic growth.

Thanks for a most insightful article.

Great discussion. I’m currently travelling back and forth to India advising on some very large scale construction projects. There is a passage in this article that reflects exactly what I have experienced – a whole host of brilliant minds but a staggering lack of ability to implement processes and procedures designed to deliver according to cost and schedule.

“…. What happens to The Big Top when the mast snaps?”

“solidarises”?

On Modi, Gujarat and India generally, the BBC doco that has caused such a stir in India, India, the Modi Story, is worth watching.