I spent 13 years of my life at Tangara School, the subject of last week’s Four Corners episode on ABC. Along with other alumni, I have spent months working with the program in their investigation into Opus Dei schools in Sydney.

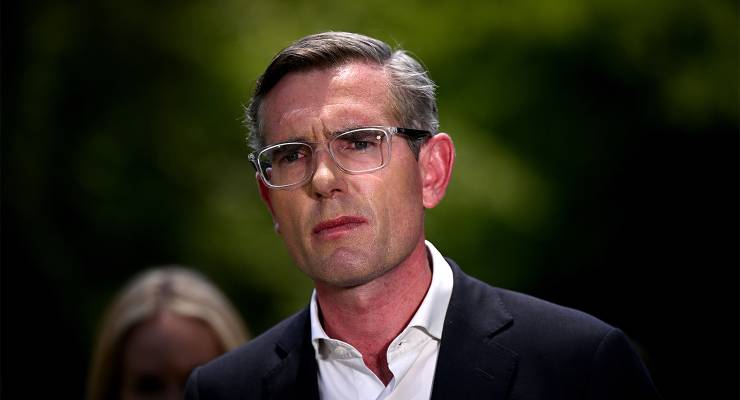

So it was incredibly disheartening to hear NSW Premier Dominic Perrottet — who I once knew personally — state: “A complaint against the schools in that program had never been made to that independent authority or the education minister’s office.”

Firstly, this is a misleading claim. A former student at Tangara School made contact with the NSW Education Standards Authority (NESA) multiple times, immediately after she left the school and as recently as 2022 when our group first approached Four Corners. In all instances, her concerns were dismissed and she was told that she would need to speak to the school itself.

What’s more, NESA’s requirements actually allow for independent schools to provide classes in addition to the curriculum, such as the religion and philosophy subjects taught by Opus Dei numeraries. This means that the student was unable to progress with a formal complaint.

So what recourse is there for those receiving an Opus Dei education when the governance of the schools is also affiliated with Opus Dei? And more broadly, if students or parents find systemic issues within a school, where can they go for support when NESA is unwilling to investigate until they have taken it up with the institution?

Perrottet also fundamentally misunderstood the silencing power of shame, particularly when it comes to children.

Since the episode aired last Monday, we have collectively received hundreds of messages from former students at Opus Dei schools thanking us for speaking up. These messages run along similar lines: “I have been waiting for this for X years” — 10 years, 20 years, even 30 years.

With this outpouring of support, I have wondered how it is possible that not one of these students has ever made a formal complaint.

I graduated from Tangara School in 2001, and it has taken me a long time to understand the damaging impact of my education. I have spent my entire adult life undoing the harmful self-beliefs instilled in me during my childhood and adolescence.

As a family receiving fee relief at a private school, our financial status was leveraged against me when I questioned practices at the school. I was told by a teacher that we were a “charity case” and asked how my mother would cope if that fee relief was retracted. I did not miss the implicit threat.

Throughout my schooling, I was told repeatedly and by many different teachers, including the then principal and deputy principal of Tangara — both Opus Dei numeraries — that I was bad and going to hell. My principal compared me to Hitler during class. She said she would pray for me every day for the rest of my life but didn’t hold out any hope for me. At the hour of my death, the Virgin Mary would turn her back on me. And so on.

This shaming usually happened publicly in front of my peers, who were told not to be friends with me because I was an evil influence. I was banned from class excursions because I was a disgrace to the school. I spent many, many hours of class time on a bench outside the classroom or in the principal’s office.

For the record, I was a devout Catholic until the age of 19. But I was singled out and branded as a troublemaker because I asked too many questions, particularly in our non-curriculum religion and philosophy classes. There was absolutely no room for discussion or debate at Tangara School.

When children are silenced in this way, it affects their intrinsic sense of self-worth – and that is precisely the point. As a religious child, when they threatened me with eternal hellfire, it did not wash over me — I truly believed in hell.

In that context, it would not even have occurred to me to complain. I didn’t tell my own mother what was happening to me at school, let alone consider going to an external body. I thought I was the problem.

At Tangara School, there are no qualified counsellors that students can turn to for support. I was encouraged to confide in my Opus Dei mentor, who was also the principal of the school — the same person who was telling me repeatedly that I was going to hell for my behaviour.

How would a child know how to go about contacting the education minister when they can’t even speak to a trusted staff member? What if they don’t feel comfortable informing their parents? And what if their parents are aligned with the values of the school? There simply doesn’t exist a clear avenue for students to voice their concerns and feel heard.

A few days before the Four Corners episode went to air, after my face appeared in the trailer, I received a message from a former parent and employee at Tangara via my social media. She told me I was ungrateful and reminded me of the fee relief and other assistance my family had received. Even though 20 years have passed, I still felt the pain of my teenage self being coerced into loyalty.

So Mr Perrottet, just because complaints have not been raised, that does not invalidate our experiences. Instead, consider that there is a culture of shaming that has kept us silent all these years.

Religious education has many characteristics of cult indoctrination.

My Catholic primary school principal, a nun, once incorrectly thought she’d heard me swear.

Proceeded to make me stand in front of the class while she “took me down a few rungs” with a lengthy and imaginative detailed character assessment that I really couldn’t reconcile with “Christian teachings”

As a small child, really great to get that sort of input /s

They wonder why their cult is dying. Kids like me grew up and remembered all the abuse.

A. Religion is a fairytale

B. Children continue to be abused under its guise.

Well done to the author for taking this crew on.

It’s well past time to end government funding to private schools.

Labor tried in the fifties, but the ghastly Mannix and Bob Santamaria terrified Catholics into forming the DLP.

The DLP propped up the Liars for decades, keeping the execrable Menzies and assorted Liberals in power for 23 years until Gough routed them.

It’s time to try again.

I think you’ll find that it was Gough who began the Commonwealth funding of private schools, purely to nail the Catholic vote. Very sad. The Commonwealth should stop doing it this instant: just hand the money to the States to put in their education funding pots. The imbalance between private and public school funding would be fixed in quick time!!

I don’t mind if people want to practise religion as a hobby, like golf, or stamp collecting.

But when they turn it into a weapon for subjugation of the poor, the very young, the sick, the aged, the marginalised, and the most vulnerable in our society – that’s beyond the pale and should not be allowed in any circumstances. Enabling and funding religious institutions to deliver legally-mandated education is absurd and should be ended immediately.

Well written Claire. It seems another politician is putting their religious and “old school club” priorities ahead of their public service

Cracking article. It’s no wonder that Australia’s political class are more religious than the general population when Opus Dei and Catholicism can do whatever god tells them is politically profitable