When news broke that Roald Dahl’s books had been quietly rewritten to excise potentially offensive language, a number of astute observers were quick to note the commercial motivation.

The rights to Dahl’s hugely profitable estate had recently been sold to Netflix for an eye-watering sum. The sanitising process had begun before the sale, much as one might hose down a pig before taking it to market.

The Roald Dahl Story Company — a thing that exists — maintained the alterations were no big deal: the texts were simply being updated to reflect contemporary sensibilities, make them a little more accessible. “When publishing new print runs of books written years ago,” it claimed, “it’s not unusual to review the language used.”

This is untrue. It is highly unusual to retrospectively rewrite the work of a long-dead author. And the motivation aligns with the most conservative, cynical and cowardly tendencies of mass consumerism. Dahl’s name is bankable, an established brand, but to maximise returns we must give the people what they want. Who cares what he actually wrote when there is a fat cash cow just standing there waiting to have its udders squeezed?

Being mean is his whole schtick

In keeping with the long ignoble tradition of censors, the omissions and rewrites are every bit as cloth-eared and ludicrous as one would expect. They have been justly ridiculed. The idea that it might be possible to sanitise Dahl by rewriting some sentences is itself ludicrous: his reactionary moralism is built into the structure of his plots. Being mean is a central component of his whole schtick. His books are constantly conflating what he sees as moral badness with physical grotesquery and doling out punishment to the wicked.

The controversy has quickly divided along predictable culture-war lines — some of the outrage is at least attributable to people’s sentimental attachment to books they read as children — but there are other issues at stake. What it exposes is the convergence of corporatised, profit-driven culture and the branch of contemporary progressivism that regards the policing of language as a driver of social reform. Publishers hire sensitivity readers for the same reason university courses have trigger warnings: because offending customers is bad for business.

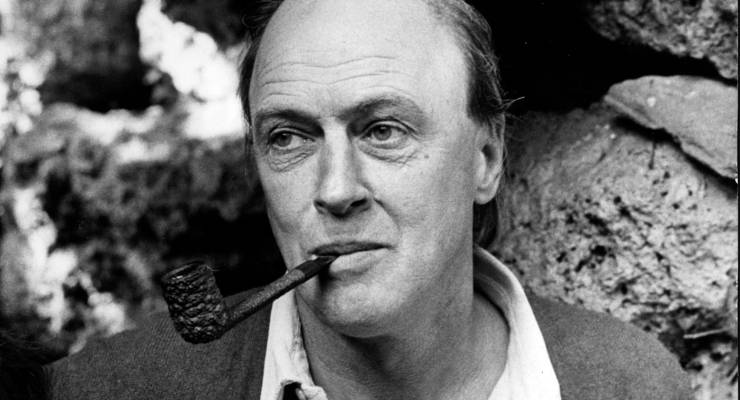

Now, I do not admire Dahl as a person or a writer. His opinions were lousy and his books are laced with racist tropes and vindictive moralism. He was a hack who knew what his audience liked and stuck to the formula.

But there is still something disturbing about casually rewriting a dead author to make his work more palatable to some hypothetical contemporary reader, whose opinions and cognitive abilities have been intuited by whatever occult means. You are, in effect, making him into someone he was not, attempting in a hamfisted way to make him better than he was, which he quite frankly doesn’t deserve. Nor do we, as readers, deserved to be served up anything other than what he actually wrote.

Censorship smacks of paternalism

It is the presumption that is most galling. In every act of censorship, however small, however well intentioned, there is paternalism. A small group makes a decision to restrict access to information and prevent everyone else from making their own judgment. Let us do the thinking for you.

What is fascinating is what the anticipated offence reveals about the assumed relationship between reader and text. At the bottom of it all are very traditional and deeply conservative notions that literature should be a mode of moral instruction and that correct language will cultivate correct values.

The assumed relationship between reader and text is one of passivity. The reader encounters a bad word; the reader is automatically harmed. This is a kind of magical thinking. It treats words as if they were spells, as if their manifestation tangibly alters the world — to write the word “fat”, even if the word is being applied to a corpulent mouse.

But reading is simply not like that at all. It is an active process of interpretation. When you read a book, you are thinking about it — or at least you should be.

Cynical though the commercial motivations may be, the changes reflect one of the persistent delusions of our time: that an intrinsically reactionary practice like sanitising an author’s work might be harnessed to a progressive end.

Dahl was an unpleasant man with unpleasant ideas, but you can’t censor your way to a better world. His young readers are far better off being exposed to what he really thought. Ignorance is not bliss and readers are not fools, even when they are children.

Literature — even ideologically unsound children’s literature — is about being exposed to unusual things, difficult things, learning how to interpret them in context and seeing them for what they are. Reading is not about making you feel comfortable by reflecting values you already hold back at you. If that is what you want, you don’t need a book. Go kiss a mirror.

Would Dahl be turning in his grave? Let us know by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

“Reading is not about making you feel comfortable by reflecting values you already hold back at you. If that is what you want, you don’t need a book. Go kiss a mirror.”

Absolutely brilliant.

Why not? What if , for me, it IS?

Then write a book yourself. The values will align magically.

Then go kiss a mirror. Simple.

Rewriting these books is a version of what Orwell described in 1984 as the job of Winston Smith and his colleagues in the Ministry of Truth. Scrubbing the past clean. Eliminating thought crime. And if it can be done with one author, where does it stop? How many books are there that offend (or might offend) somebody, somewhere, and would benefit from a few judicious alterations?

Nobody is forced to read Dahl’s books. If you don’t like what is in them, read someone else’s books. Or write a better one yourself, under your own name, not Dahl’s. Let his reputation be as it should be, based on the books he actually wrote, not some ersatz revised version he would never recognise, put together by an anonymous sensitivity committee.

Hear, hear. Incidentally, we can all have our own view of Dahl’s writing. And some of us can have views about his character. I did not know Dahl, so I cannot say whether he was an “unpleasant man”. I do know that at one stage of life he had anti-Semitic views, which in my view is a heavy black mark against his views then. A relative who lived in the same town as Dahl did later in his life told me nothing against him. As to his writing, we read his books to our children without feeling that we were endorsing a pernicious morality. Our view was that he used literary devices similar to those employed in fairy tales to reject meanness and selfishness and to encourage children to assert themselves against forms of adult oppression. Charles Dickens does the same, without salient fairy tale tropes , in a number of his books, including “Hard Times”, “Oliver Twist”, “David Copperfield” and “Great Expectations”.

Kids love Dahl, its just a fact. My boys loved all the stories as they were dark,scary, strange and funny. If he’s a hack then he’s one hell of a creative heck, where does one begin on how these stories resonate with kids? Yes there is so much that is problematic about them ,but truly so what, why are we trying to erase everything that doesn’t fit the 21st century more we are living in? I’m astonished that there is not a greater outrage at what this means! We are censoring what is perceived as “offensive”, a massively subjective process. The word “fat” as a descriptor is a problem? Why is that a problem, he’s describing a character he created and he decided to describe the character as “fat”.

Are we collectively alright, am I missing something here? They are fiction, made up kids stories, written at time that reflected some, not all, different values, and yet….they have a universal appeal. We all know Miss Honey is an appalling stereotype, but that’s what Dahl did, and its one of the reasons why Matilda is so hugely popular!

My sons are 15 and 18, so they read him in the 21st century and they loved them, just as they loved Big Nate, Tashi, and the Treehouse books etc etc etc. If someone doesn’t want their kids to read these books, then read something else. Where does this stuff end? Is there going to be a re write of A Christmas Tale? “Scrooge is not just a grumpy old man – he is a “squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner”. Gee let’s get the sensitivity readers to do a good re write on that, and how’s about when people are reading the Hebrew Bible to their kids, about all those parts of Exodus that outline the conditions in which you can sell your daughters into slavery? Time for an edit?

Where does this end?

The originals are still very much available. Are you arguing that no alternative versions should be allowed to exist?

In his name .. yes.

Perhaps it’s more about reading books written at a time when people could get away with writing such stuff and if you’re an aspiring writer, (as a lot of child readers sometimes are), learning and understanding that what is in those older books doesn’t fit with modern times. Books help teach critical thinking. If we don’t have books that make people feel uncomfortable, how are we to know when something just doesn’t feel comfortable to us and we ask ourselves why?

If there are alternate versions, they should be clearly marked as such. Including the change in authorship. I prefer the originals of any work in any case, usually in their original language – for the same reason.

Great piece. When Bowdler sanitised Shakespeare, he became a figure of derision. This sort of censorship is just as bad.

I thought something similar. Along the lines of “this censoring and rewriting of a dead author’s work is what made the Bowdler editions of Shakespeare the definitive versions that they are today”.

Agreed James.

Are we to have mass book burnings, Fahrenheit 451 anyone?

The Old Testament could be rewritten to erase many ideas which are not currently acceptable.

Similarly removing statues of people whose actions are not currently acceptable. They are there because they reflect society at the time. By all means comment on them, but erasing them loses that opportunity. There doesn’t seem to be an inclination to do the same with WWII.

Where moralist censors rise, there is always potential for a counter-offensive that might be create the very opposite of that which the moralists desired? Take, eg, ~40% of Australians who declare ‘no religion’ in the Census. Imagine if a sizable portion demanded to see the Bible sanitised or reclassified as fantasy or removed!

Apart from inciting another lions and the others war, it serves to demonstrate how those who wish to control the world in their order could hypothetically create their own cataclysmic nightmare. Careful what you seek might apply here.

We cannot control ‘it’ all, whatever ‘it’ is. The best we can hope to achieve is control of our own tolerance and acceptance of the different ways in which people choose to be influenced and live. That must not include their presumption to remove the same choice from those who think and live differently.

A stunning example of countering moralism exists in West Wing ‘The Midterms’ S2 E3 https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0745700/