It’s the $368 billion friendship bracelet that the Greens suggested would lead to “floating Chernobyls” off the coast of our major cities, and marks the first transfer in history between a nuclear-weapon state of nuclear-powered submarines to a non-nuclear state.

So just how dangerous are the three AUKUS-born nuclear submarines we’re getting from the US, and the eight we plan to build by 2055? And is there enough nuclear material onboard or around for us to be afraid of a meltdown or malfunction?

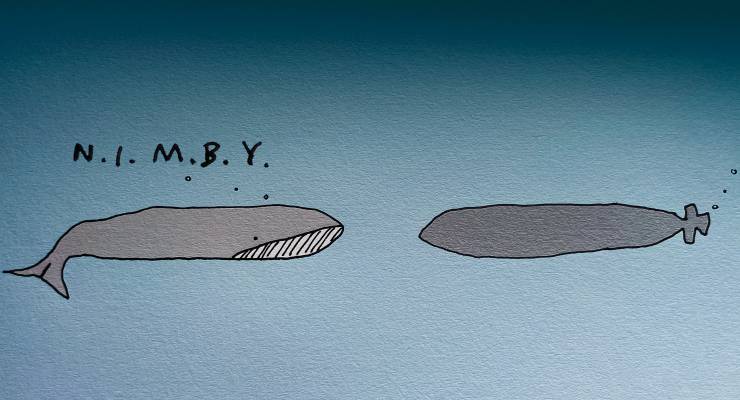

Following the announcement of the deal in September 2021, Greens Leader Adam Bandt told the ABC it was a “dangerous decision that will make Australia less safe by putting floating Chernobyls in the heart of our major cities”.

But Bandt’s words were mostly theatrics, Professor Andrew Stuchbery tells Crikey. He’s the head of the Department of Nuclear Physics and Accelerator Applications at ANU, and says the reactors in the US Virginia-class nuclear-powered submarines are nothing like the Chernobyl reactor.

Plus, he says, “it is likely that the submarine reactors will be sealed up for life — Australia will be doing limited maintenance on the reactor”.

Stuchbery acknowledged that Australia doesn’t have specific expertise to service the submarines right now, but says our track record of “operating and maintaining a nuclear reactor that requires more regular intervention (refuelling) than a submarine reactor” speaks for itself.

In a statement to Crikey, the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO) said it had “safely and securely commissioned and managed Australia’s three nuclear research reactors” in its 70 years, and called Australia “one of the world’s most sophisticated nuclear nations and a leader in a range of nuclear disciplines, including security operations”.

ANSTO said it wasn’t a “credible comparison” to put a “poorly managed” power plant meltdown against today’s naval propulsion reactors, though said there’s “no doubt the devastation of the Chernobyl disaster still stands prominently in the nuclear timeline”.

Griffith University emeritus Professor and radiation and nuclear safety expert Ian Lowe agrees that any sort of nuclear accident is unlikely. The US and UK have had nuclear submarines for decades, Lowe points out, and neither has experienced an issue of that magnitude.

But that’s not to say there isn’t reason to worry about Australia acquiring nuclear subs, Lowe says. Look at the former USSR, which lost as many as nine nuclear submarines either by accident or by sinking them in the northern oceans.

“They are quietly sitting somewhere on the sea bed, where they will eventually disintegrate; we can only hope the containment vessel around the nuclear reactor prevents the release of their fissile material.”

The AUKUS submarines are nuclear-powered but will not contain nuclear weapons, as US President Joe Biden stressed last month. But each of the Virginia class submarines does carry 200 kilograms of highly enriched uranium — nuclear weapons-grade material — which will need “serious military security to ensure it isn’t misused”, Lowe says.

For context, he says, that’s more than three times the amount of enriched uranium used for the bombing of Hiroshima.

“Even back in the 1960s when I was quite enthusiastic about the prospect of nuclear power, I thought it was stupidly dangerous to put nuclear reactors in warships, given that an enemy would be trying to destroy them in any serious conflict,” Lowe says.

Plus, we’re volunteering to try to solve a problem neither the USA nor the UK has solved yet, he adds: “managing the high-level radioactive waste that we will have at the end of each submarine’s life”.

In inking the deal, Australia committed to processing all the radioactive waste generated by the submarines, including “radioactive waste with lower levels of radioactivity generated by day-to-day submarine operations and maintenance”, a government fact sheet reads, “and radioactive waste with higher levels of radioactivity, including spent fuel, which is produced when submarines are decommissioned at the end of their service life”.

Defence Minister Richard Marles called it a future problem that we wouldn’t encounter for decades yet, telling Parliament in March that “we will not have to dispose of the first reactor from our nuclear-powered submarines until the 2050s”.

Nuclear waste isn’t something Marles should just wave his hand and say that something for someone in 2050 to work out. We’re talking about waste that will need to be securely stored for thousands of years.

At least Marles is secure in the knowledge that he won’t have to think of a solution.

Without getting too science-fictiony, constructing a magnetic hoop accelerator in the North of Australia (as close as possible to the equator) would enable the waste to be disposed of by tossing it into our very own captive reactor – the sun. The technology already exists in a smaller version as a railgun achieving Mach 8.8. Scaling it up to lob 500kg lumps at escape velocity shouldn’t be too hard.

Or better still, don’t waste our hard-earned on guaranteed white-elephants in the first place.

yes well that runs the risk of something going wrong and just spreading nuclear waste around the world.

Hence Northern Australia…………

In the event of a mishap, the projectile ends up in the ocean.

It should, however, be much safer and more reliable than using rocket technology. Providing there’s no power cut, there is almost nothing to go wrong, and the projectile itself is simply a metal container, so no pyrotechnics.

Particle accelerators use the identical technology, but achieve massively higher velocities (a perceptible fraction of light speed).

Great idea and include as passengers all those advocating this idiocy in the projectile when it is fired into the Sun.

Two problems solved for the price of one, don’t even bother with oxygen or life support systems.

Over the next day or so, we will all hear the phrase ‘Lest we forget’ countless times, and countless pleas to honour the memory of the fallen, especially the Diggers who sacrificed so much in the Great War. Blah, blah, blah.

Well, I’m old enough to have had the privilege of speaking to some of these veterans first hand, and even more veterans of WWII, and if there’s one thing that every single one of them said – and every single interview of an old vet has also repeated – is that ‘it should NEVER be allowed to happen again’.

So, how are we now showing our respect for these old Diggers, now that none of them are here to speak for themselves anymore?

We are talking about spending $350 billion on nuclear submarines.

Not forgetting the half BILLION being on the War Memorial to exhibit/advertise the killing machines of Raytheon/Northrop Grumman and other Masters of War.

I wonder if their ads will feature on the interactive displays………………………..

The perfect institution to include the Lest We Forget Nuclear Waste Dump.

To be clear, the perfect institution to house the Lest We Forget Nuclear Waste Dump. That will make it a real warm memorial.

Just hang up the Oils’ Red Sails in the Sunset album cover.

We should be saying “We Just Forgot!”………………..

If the Yankee warmongers (and their “Coalition of The Half-Wits”) get their way there won’t be anybody left to say it afterwards.

Same here, Graeski. I too had to speak to vets too in a professional capacity (mainly WW2 and Vietnam) and was struck by two things:

The entire non-discussion of USUKA is predicated on their being predators at the behest of an imperium – we are not even mercenaries because we are paying to play at being all growed up.

They are NOT for the defending this country nor territorial marine zones from encroachment which the RAAF & RAN do perfectly well.

“The US and UK have had nuclear submarines for decades, Lowe points out, and neither has experienced an issue of that magnitude.”……….

I’d say the sailors onboard the USS Thresher and the USS Scorpion would take exception to that.

Sinking without trace is quite an issue for those involved………………

…………and how do you know that they (and the 7 Soviet missing subs) didn’t sink because of a reactor meltdown?

Nobody is going down to check.

You wouldn’t have to. A meltdown would release fissile material into the environment which would be immediately detectable. And they are actually going down to check. The USN monitors the sites of both the Thresher and the Scorpion on a regular basis (so not “without a trace” either, both wrecks were located shortly after their sinking) for evidence of radiation entering the environment. So far none has been detected (at least not that they have admitted to any way).

Of the 7 Soviet/Russian subs, reasons for sinking are less obvious because the USSR/Russian Federation is even less forthcoming with information than the Americans. As far as can be ascertained:

K-27 – dodgy reactor throughout it’s service. Sealed up and deliberately scuttled.

K-8 Fire on board while in the Bay of Biscay. Sunk while being towed.

K-219 Fire in a missile tube during a test fire. Sank while being towed

K-278 Komsomolets Fire on board. Most crew evacuated

K-429. Sank twice! Both in shallow water, once during a test dive, the second time at her moorings. Was decommissioned shortly afterwards.

K-141 Kursk Torpedo explosion. All of the vessel, except for the bow section which was destroyed, salvaged

K-159 Decommisioned, left at dock with the Russian navy unable to do anything with it due to lack of funds. Broke free of her moorings in a storm and sunk.

Really only K-27 is a confirmed reactor issue, but rather than a meltdown it appears it was deliberately “disposed of” in deep water to avoid having to deal with it. And comparing an early version Soviet sub reactor with the ones in the Virginia and Astute class boats is like comparing a Model-T Ford with a Tesla Model S Plaid.

“(at least not that they have admitted to any way).”…………..

Somehow I doubt they’d be owning up. That would mean acknowledging their submarines had a problem.

Not overly conducive to persuading people to sign up.

The K-27 and the K-159 both represent ongoing problems – more so the K-159 (which in fact sank while being towed to Murmansk, killing nine sailors who had been onboard to bail out water in transit). The sealant around the reactor in K-27 was only designed to last until 2032, and as the reactor is still fully loaded and it is only sitting in 33 metres of water, poses a significant risk.

Because of the involuntary nature of the K-159 sinking, there were NO measures taken to safeguard it’s reactors, which still contain 800 kg of (highly enriched) spent fuel. It’s hull is rusting out and in a survey in 2021 showed several breaches.

Both were due to be part of a joint East/West effort to raise six significant sources of radiation from the sea-bed and “safely dispose” of them (sure – so they join the other 200 monster storage tanks at Sayda Bay where they will sit for a couple of decades while they “cool off”).

Then Putin invaded Ukraine.

End of co-operation.

Your work touches on the very important unanswered issue of nuclear powered war ships. What happens in combat? To date, no nuclear ship or submarine has been hit or destroyed by enemy fire in conflict. Some have definitely participated in conflict, but always on what was essentially a ‘one way range’ (no one firing back with any real prospect of causing harm). Whether at sea, tied up in dock or up on the ‘hard’ getting serviced, these targets come with an as yet untested question mark. What happens when they’re hit.

What would happen if a nuclear submarine was hit while in port? This would be a likely scenario as there are always submarines in dock. Well, what would happen? Would a Hiroshima sized spread of radioactive particles be distributed widely across the unfortunate host city?

Richard Shortt insinuates something horrible by saying, “what happens when they’re hit?” He does not describe a credible hazard, but instead leaves it to your imagination that something unspeakable will happen. Indeed, it is hard to invent a semblance of catastrophic consequence of naval action. Sure, a warship may be holed and sunk to the sea floor, taking its stopped reactor with it. It is an unlikely event that a missile could penetrate the ship’s armour, intervening bulkheads, biological shield, pressure vessel and only then detonate, it would still mainly crumple the zirconium cladding before splintering some of the uo2 fuel ceramic into the sunken wreckage of the ship. The ceramic is chemically resistant, so most of the fission products will decay away in place rather than leach away into indefinite dilution.

so you’re saying, that a nuclear sub can be holed and sink, taking all onboard with it, but the reactor core will never, in any scenario, be breached … or at least, not for a few thousand years while the fuel harmlessly decays – can you provide references to back up this assertion?

The engineering would suggest this to be the case. No absolute guarantees mind you, but even if struck directly the reactor will be a dirty bomb contaminating a limited area, not a Hiroshima/Nagasaki type wide spread explosion. Once the fuel cells are all separated by blowing the thing up they will no longer be at critical mass so any self sustained chain reaction will immediately cease. The left overs will still be really dangerous, but they won’t explode in a giant mushroom cloud.