Renters are paying landlords even more than the asking price for a rental property, according to new data, revealing the rental crisis is even more acute than we thought. With rental vacancies lower than ever before, the practice of offering extra to win the property is apparently widespread, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) has revealed.

We already knew advertised rents were rising higher than average rents. If people with existing leases were paying $500 a week, for example, the asking price for new renters would be $600 and rising. Data from property firm CoreLogic showed advertised rents had risen 22% since the start of 2020, while the average rent overall had risen just 5% since mid-2019, as the next chart shows.

Rents*, June 2019 = 100

The reason for the difference is simple: not all rental properties get new tenants each year. When landlords get new tenants they are more likely to vary the rental price. The lower series is the one that feeds into the consumer price index (CPI), even though if you’re shopping for a new rental property it is not relevant. This causes CPI to be lower than it would be if advertised rents were used.

Despite the enormous difference between advertised and total rents, it turns out advertised rents are actually an underestimate. What tenants end up paying is even higher. Actual rents paid by new tenants are up 24% since the start of the pandemic, according to ABS data drawn from a new database of 600,000 rental properties.

That suggests tenants are bidding up the rent in order to win the property. Soliciting higher bids is illegal in Victoria, but nothing stops prospective tenants from looking at the seething crowd at a property inspection and realising they need to do something extra to end up with their name on the lease. Rental vacancies have never been so low, and anyone who has tried to rent recently knows how competitive the rental market is.

Despite the rapidly rising price of rental properties, there is some good news in the rental market. It turns out that some parts of Australia are still cheaper than they were pre-pandemic.

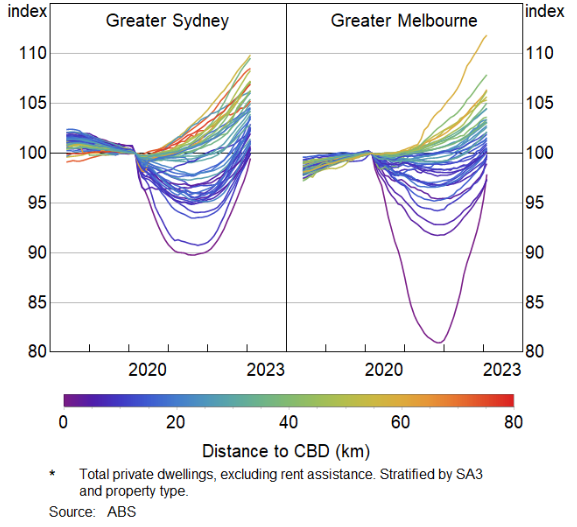

In particular, inner Melbourne and inner Sydney. Neither area has recovered their pre-pandemic rental prices. Sixty-two per cent of inner Melbourne property (defined as property within 12.5km of the CBD) is still cheaper to rent than pre-pandemic; for Sydney, the figure is 49%.

So if you live in a tower with a windy balcony that affords a view of another tower, you’re probably wondering what all the fuss is about. Your rent is rising, but it’s still below where it was. This is partly due to a lack of students who would usually occupy inner-city apartment buildings. It is also partly due to the pandemic and associated lockdowns, which saw people flee small inner-city homes that were optimised for short commutes and instead move to large homes further from the city, complete with recreation space and home offices.

However, the phenomenon of cheap inner-city rents is in retreat, with inner-city rents rising rapidly towards their early 2020 points. But they’ll need to rise even more to catch up with some outer-suburban locations, as the next chart shows.

Rent price indices *, by capital city SA3, March 2020 = 10

The rental rankings have also been turned on their head by the events of the past three years. It’s not just inner-city rents that became cheap, whole states are now on special.

The highest rents in Australia are now in the ACT, averaging $560 a week, while the lowest are now in South Australia, at $380 a week.

Victoria used to look expensive to the average West Australian renter, but the average rent there is now lower than those in WA, and lower than Queensland too. Victoria is, in fact, barely more expensive to rent in than Tasmania, the new data shows. Partly that’s a composition effect, because of the higher proportion of apartments in Victoria than in Tasmania. But it also reflects population flows, with lots of Victorians and visitors to Victoria simply fleeing in recent years.

Still, the logic of the market is that every cloud has a silver lining and every action has an equal opposite reaction: lower rents in Melbourne will surely help draw residents in and help it grow even quicker. That could help in cementing its newfound status as the biggest city in Australia.

Contrast the wall-to-wall war promos on Anzac Day with the political determination to make Australia unaffordable for us who live here. A third of us rent, a third of us have a mortgage.

Housing unaffordability makes increasingly precarious lives more vulnerable: tenants fighting to hold onto ever shorter tenancies, with their rights as renters eroded, are more likely to become homeless. They are more likely to be in debt just to meet the cost of living, on low incomes, or in receipt of benefits – often both, accumulating the kind of expensive credit that makes financial catastrophe a real and imminent threat. In particular, they lack financial reserves.

These marginalised are the “precariat” – marginalised citizens with few effective rights. Volkofsky & Brown manages nine apartment blocks in Sydney’s CBD. Its owner said it no longer shocks him when he finds 20 people living in a two-bedroom unit.

Ignored by the two dominant conservative political groups– except to protect the property pimp/spiv donations. Media likewise – focussed on its income from the Property Liftouts.

While there’s been a lot of criticism of landlords, don’t forget the real estate agents. They are one reason why the longest standard lease for a house or an apartment is one year. This is partly because it makes it easier to lift the rent, but also because they take a week’s rent as a part of their fee every time a new lease is signed.

The rental accommodation crisis is an utter failure of the ‘market’ in which we are urged to believe is the source of the solution.

The practice of allowing bidding for a tenancy is an obscenity that needs to be brought under control. Desperate people will do desperate things to get a roof over their heads. Again, I refer any reader to The Grapes of Wrath where the Okies continually bid each other down in order to buy food. It beggars belief that State and Federal Governments are turning a blind eye to this, but then, hey, the Property lobbies have a lot of power.

Good analysis. Too many “rents are rising’ stories don’t get into the weeds of “rising where and for whom?”. Location and type of rental tells us the real story about which sectors of the community are facing difficulty.