Australia is one of the world’s richest countries, but our government taxes and spends far less than most other OECD members.

For decades, the richest 10% of Australians have been capturing a growing share of income, while the poorest 10% remain trapped in poverty. The stage three tax cuts will widen this divide and entrench the structural budget deficit. This is bad policy that runs counter to Australia as the land of the fair go.

What are the stage three tax cuts?

In the 20th century, Australia was one of a select group of rich nations to develop a progressive income tax system. In 1950 we had 28 tax brackets, with a top marginal rate of 75 cents in the dollar. That kicked in when annual income ticked over £10,000, which was about 33 times the average wage of a male factory worker.

Today there are five brackets with a top rate of 47% (including the Medicare levy) for incomes above $180,000 (roughly double the full-time earnings of an average male).

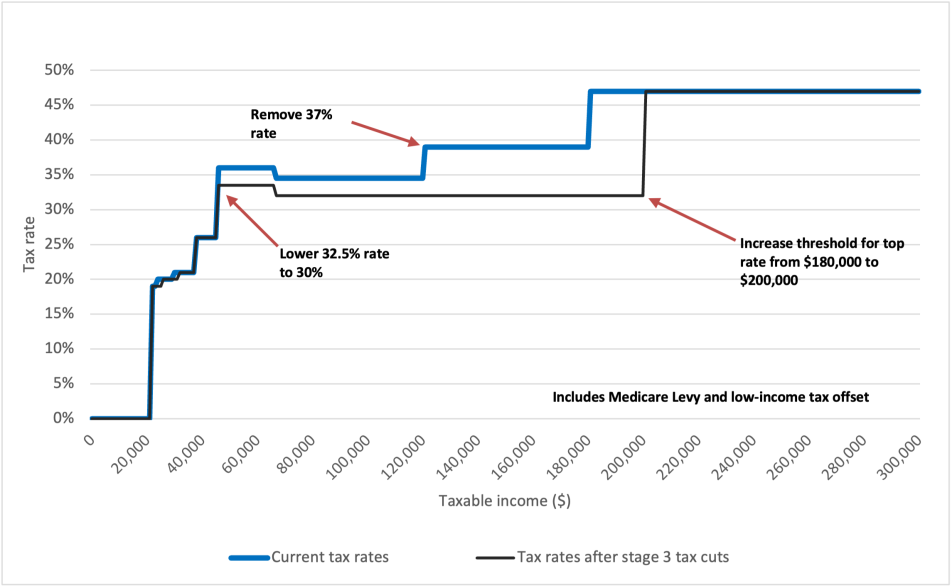

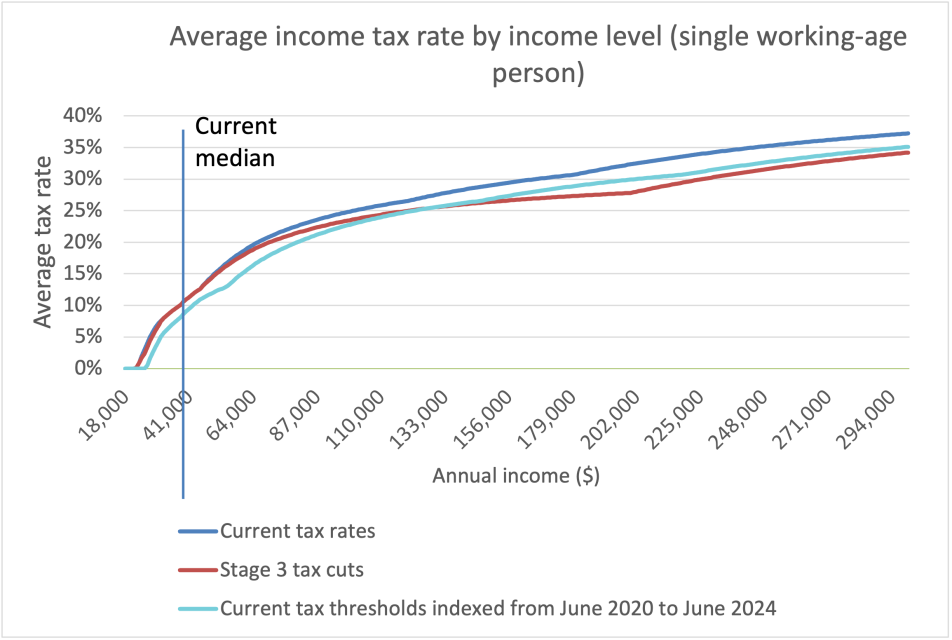

The stage three tax cuts will further flatten and compress the progressive rate structure by increasing the threshold for the top rate from $180,000 to $200,000. It will completely remove the 37% tax bracket and lower the next tax rate from 32.5% to 30%. This will then be the rate that applies to all income between $45,000 and $200,000.

Distributional effects v adjusting for inflation

These tax cuts significantly reduce revenue and shift the burden of taxation away from top-income earners and towards low- and middle-income taxpayers. They overcompensate high-income earners for bracket creep (the rise in the share of income paid in taxes due to inflation) while doing little or nothing to address the issue for Australians on lower incomes, who will pay more tax after the removal of the low- and middle-income tax offset from July 1 this year.

Less revenue means less spending on poverty-alleviation

The tax cuts will reduce government revenue by about $184 billion in the first eight years — that means less money to spend on alleviating poverty to improve fairness and social and economic outcomes overall.

For example, the estimated $54.1 billion in revenue forgone over the forward estimates from 2024-27 could more than fund the combined cost of the $34 billion needed to increase JobSeeker and rent assistance to a liveable rate over the same period, the $10 billion Housing Australia Future Fund, and the $1.1 billion needed to restore the single-parent payment to continue until the age of 16 for the youngest child over the same period.

A progressive income tax is achieved not just by the rate structure but also by the base –— that is by what income we choose to tax.

When Australia’s income tax was enacted more than a century ago, we taxed income from capital at a higher rate than income from work. That differential was removed, but in the 1980s Australia introduced a capital gains tax and other reforms to significantly broaden the income tax base.

Since then, tax concessions have crept back into the law in favour of capital income. These include the overly generous capital gains discount, excessive concessions for superannuation, and negative gearing. As higher-income earners can save much more than low-income earners, this narrowing of the tax base reduces revenue and makes the tax system less fair.

As the commitment to a progressive income tax rate and broad base has declined, inequality has risen, pushing the tax burden onto the middle and benefiting the rich. Top-income earners pay a large share of tax in our system because they have more capacity to pay, but the many avenues available to well-heeled taxpayers to shelter wealth and income mean it is unlikely they pay anything close to the statutory tax rates on their actual income.

It is often argued that tax rate cuts and concessions foster economic growth. But today’s economic research suggests that taxing capital adequately is both equitable and efficient and highlights the economic damage done by growing inequality and poverty. This argument also ignores the growth and social benefits delivered to Australians by increased spending on public goods such as health, housing and education.

How to fix it?

The stage three tax cuts should not go ahead as currently designed. The government should at least return the 37% tax rate at a suitable threshold, which the Grattan Institute estimates would save $8 billion a year.

Australia needs a broader discussion about restoring the progressive rate structure and base of the income tax to capture more tax from capital and wealth. This would ensure people pay a fair amount of tax based on their ability to pay while raising the revenue the government needs to provide the services and infrastructure Australians expect and need.

Written with Professor Roger Wilkins, Professor Guyonne Kalb (Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research) and Mr Peter Mares (Centre for Policy Development)

Should the government scrap the stage three tax cuts? Let us know your thoughts by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

The tax cuts came in 3 stages. Labor wanted to pass the first 2 stages to give some small measure of relief to the lowest paid. The Morrison Government refused to split the legislation which forced them to agree to all 3 stages. This was always a strategy to give cuts to the well off supporters of the LNP thinly disguised with some crumbs for the low paid.

Labor fell for it. They may have had no option but they should never have guaranteed to keep them in place. It is not just a variation in tax but the elimination of a whole tax bracket. They should be ditched immediately. Labor can weather the resultant LNP abuse and can even turn it back onto the LNP looking after the rich.

Why keep saying they ‘fell’ for it? They voted for it. They could have had some spine and not vote for them at all and just say that the coalition wanted to blow up tax cuts for lower wages because they REALLY wanted tax cuts for high wages. Labor just sucks at prosecuting anything.

How was Labor “forced to agree”?? They could have voted no.

Labor got wedged. Albanese’s lot still seem to think that rich people might vote Labor if they give them enough handouts, and they were scared that refusing to vote for these tax cuts would lose them some of those votes. I have news for Albanese, and it’s not good – although i am one of the poorer people around, I still manage to scrape up my golf club fees. I therefore hang around on the golf course with a lot of people who are going to do very well out of these cuts. Not one of them would ever vote Labor for any reason whatsoever (they won’t vote for the Voice either, but that’s another story), so he’ll get nothing out of this misplaced magnanimity.

They were “forced to agree” because they wanted the low paid to get the tax cuts. Their mistake was to tell people they would not cancel stage 3. That was what was gutless.

They could have, but were wedged on the issue, not wanting to appear ‘weak’ on matters economic. Much the same as AUKUS.

The issues dealt with in this article get to the very heart of the kind of society that we live in. The matters canvassed in the essay illustrate so vividly the fact that we live in a capitalist society that caters to the greed of the rich (especially in the legal and financial senses) over all others.

Indeed, the brief reference to the taxation system that obtained during the reign of Prime Minister Robert Menzies, suggests an almost socialist economy was in existence at that time (that is, compared with what prevails now). To have described the economy that Menzies presided over in those terms (i.e. as ‘quasi socialist’) in the 1950’s or 60’s would have been laughable then. In fact, it is not only the taxation system that appears to be almost socialist in comparison with what we have today, it is the fact that back then we also had social ownership of gas, water, electricity, postal and telecommunications services and government-owned banks and insurance companies (not to mention publicly owned shipping and airports). Even in that environment, we had a Communist Party of Australia to advocate for a still fairer society.

Obviously, this more egalitarian form of society was too much for the rich and powerful. They have gradually eroded the meager benefits that formerly flowed to the less well-off over the intervening decades. The Communist Party no longer exists and the Australian Labor Party is now ‘in the pockets’ of the ruling class. The oligarchs are now creaming more of the wealth off that is created in this country than has been the case for many decades; very little is said about that and even less is done about it.

Clearly, the ALP should never have obligated itself not to scrap those hideous stage three tax cuts before the last election. It is now ‘hoist with its own petard’ in that regard. I can understand the desire of the Labor Party not to break its election promises. As I have said before, perhaps the only way around this conundrum is for the party to acknowledge its mistake publicly, remind electors of the huge demands that are being placed on the budget now and will be placed on it in the forthcoming years, and go to an election on the issue. The ALP should consider not only getting rid of these cuts but also undertaking a major review of taxation (although knowing the ALP as I do I am not sure that they could be trusted to do the right thing by ordinary Australians with respect to that last suggestion). A much more progressive taxation system is much needed.

so well put-The crazy thing is and we know it as fact; the liberals broke many election promises ; no cuts to the ABC, no cuts to Medicare ..

This article would be greatly helped by a graph of 1967 tax brackets (I pick this as the first year after decimalisation, so it will be easier for most people to understand), compared to the same thing today. It should also be overlaid with highlights for minimum, median and mean wage, and some big multipliers (2x, 5x, 10x) of the average. Cherry on top would be showing where the percentiles of taxpayers fell into this structure.

Also, it should not perpetuate the myth that Federal Government spending is constrained by tax revenue. The point of taxes is not to fund expenditures.

Crazy how in a handful of short sentences you’ve put yourself entirely above the national conversation on the subject.

I am not sure what you are declaring here. If you refer to the last two sentences, drsmithy is absolutely correct. Taxation is levied, necessarily, to provide policy space for the government and to ensure the value of the dollar. Most of all, taxation is and should be used to encourage behaviour the government wants and discourage things it doesn’t. A progressive government would, we hope, tax to create a fairer, healthier and more equal community. A neoliberal government believes that it should favour the private sector, its mates and the rich and powerful. Unfortunately, both the ALP and the LNP use the excuse that the availability of “taxpayers’ dollars” constrains their ability to implement difficult reforms.

ethics, facts , accountability, compassion and responsible govt equate to smart decisions ….waiting…..

You could replace ‘tax cuts’ with ‘AUKUS’.

It’s almost as if alleviating poverty is not actually a goal …

Now you’re getting it…

It would be so very easy for Labor to turn ditching the cuts into a political win, that the fact they’ve only ever leant in the other direction should tell you something.

They want the tax cuts. I don’t know why. I don’t know why anyone with a functioning brain would want them, but they most certainly want them.

Anyone holding their breath for Labor to drop the cuts is on drugs. New boss, same as the old boss, and yeah, we’re getting fooled again.

Less and less are and were fooled, Kimmo. Labor’s primary vote was low to appalling. We’re on track for minority governments, just need a few more rusted ons to shuffle off this mortal coil. Maybe not even that- Millennials and Gen Z have the numbers, now and they’re not becoming conservative as they get older. I suppose it’s hard to become conservative, complacent and comfortable when you’re being royally shafted every which way.

The place is being flogged off via nefarious multnational funded and oriented lobby and interest group investor class – and all these plum roles for the ‘players’!.