There’s a touch of distracted unease among Australian opinionistas as they sniff what smells like the No case heating up with repeat wins in the Canberra-dominated daily media cycle.

Across media — traditional, new and social — the commentariat are pointing to the opinion polls (usually the ones their bosses have paid for) with a bit of free campaigning advice to the First Nations leaders who’ve done the hard work of forcing the Voice onto the national agenda.

Perhaps they’re remembering that moment when once-was opposition leader Bill Shorten parlayed his three-year domination of the daily news cycle and consistent leadership in opinion polling to victory in the 2019 election.

No, wait. I mean, they’ll be remembering how it was the failure of then-opposition leader Anthony Albanese to properly contest the daily news cycle through the pandemic that led to last year’s inevitable reelection of the Liberal government to chants of “How good is Scott Morrison!”

Right now, Australia’s traditional media can’t get out of their own way long enough to learn from their own mistakes. Instead, they’re hearing the increasingly hysterical shouts of “no” from the right and thinking: “That’s conflict. That’s news.”

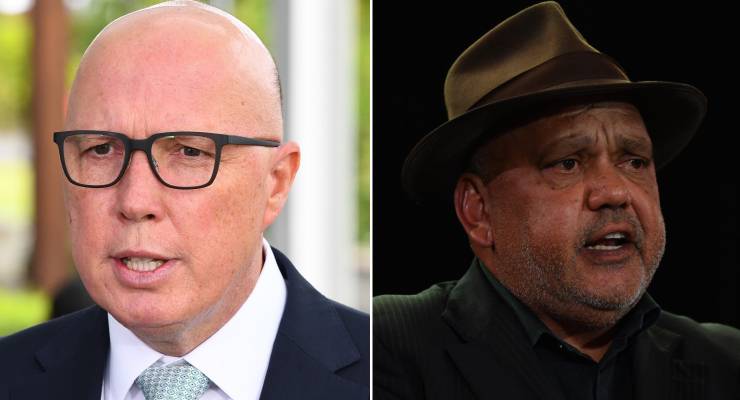

The hunger for reportable conflict is encouraging the now-Opposition Leader Peter Dutton to pedal ever harder, moving his way up through the outrage gears to keep himself at tête de la course — and at the head of his party. That pressure has carried him in just six months from last summer’s “show us the details”, through the chin-stroking debate over the constitutional questioning of advice to executive government, before forcing him to his post-Aston byelection declaration of no and, finally, to last week’s odd “re-racialising” neologism as code to deny an Australian identity that incorporates and acknowledges the identity of First Nations.

Each gear change is a sign of the No campaign’s weakness, not its strength. It risks a dog-whistle pitched a bit too low — low enough to be picked up by an appalled human ear.

The “only the new is news” journalism practice is, on big cultural shifts like the Uluru Statement from the Heart, precisely back-to-front. Outside Canberra, it’s the reverse that’s true: not much alters from one day to the next. But over the long term? Everything changes.

Australia’s traditional media need a new organising principle (h/t Jay Rosen): “Not the odds, but the stakes.”

Outside Canberra, there’s a better understanding that we’re now more than three decades into Australia’s post-Mabo attempts to reimagine itself as a reconciled community that’s come to terms with its own past.

That imagining has changed Australia’s culture, but the hard politics of embedding that change hasn’t kept up. We’re adopting new stories about ourselves with understanding about the frontier wars and the richness of pre-1788 life. We’ve absorbed new rituals like Welcome to Country, the embrace of First Nations flags or the use of Indigenous place names.

The Uluru Statement from the Heart is the gift that allows our politics to catch up with our culture. And the real politics — not the Canberra stuff, but the real grassroots work of building change — is already happening, outside the gaze of traditional media.

The less you have to do with Canberra, the greater the confidence that the Uluru Statement’s now six-year-long march through Australian institutions and communities is biting deeper than the increasingly desperate lurch for the headlines by the federal opposition.

Looking through those cultural imaginings, a yes vote on the Voice is the inevitable next step of the Voice-Treaty-Truth road that we’ve branded as “reconciliation”.

It’s the no vote that’s dangerous. No is a vote for a U-turn, to repudiate the 30-year reconciliation project.

Leading Voice advocate Noel Pearson has laid out the stakes of a no vote for reconciliation: “It’ll die. It’ll be dead.” As he told a parliamentary inquiry back in March: “If fear-mongering about it resulted in a no vote, it would be a complete tragedy for the country. I don’t know [how] you could pick up the pieces after that.”

The good news is that once Parliament approves the referendum in the next few weeks, the Voice news cycle will be riding out of town, away from Canberra’s party politics, far from the advice of the media commentariat, into the communities that have been long imagining an Australia that says yes.

I’m watching the polls with interest but nothing more. The volume of media hysterics would have had us believe that the federal, Victorian, NSW and Aston elections would all be won by the Liberal/Coalition offerings, but the ‘Quiet Australians’ prevailed.

It’s entirely possible that the referendum will be the same. Dutton’s identity shift from Call me Cuddles to Pauline v2.0 might play well with the racists, but I really wonder how it will be received by ordinary Australians when they start paying attention and see there’s also an argument in favour of a Voice and it doesn’t rely on fear and hate.

hilarious

Those friends/neighbours/aquaintances who read The Australian have all indicated they are voting no. NewsCorp wasn’t able to swing the 2022 federal election, let’s hope the trend continues.

The Australian is almost cheer leading the NO Case, with multiple articles on a daily basis pushing the NO case.

And, so they can claim balance, all of these NO artifices are interspersed with the occasional YES case article, but the Trend is obvious.

And the vitriol in the the comments sections of the NO articles is fierce. I knew there has always been an undercurrent of Racism in our Country, but I didn’t realize it was so extreme.

Rah rah! Have they got their pom poms and skimpy outfits? That would be worth the front page, just for a laugh…

The only trend stronger than the hunger for reportable conflict is the flood of commentators analysing the media coverage of reportable conflict.

Why don’t journalists find and report original news any more?

Because it requires effort…?

Because it’s s cheap to do and enough of us are still prepared to pay for it through the indirect, hidden, journalistic costs embedded in so much of what we buy?

In my neck of the woods, “The Voice” needs to find a way to keep the message way simple.

We already are divided by the constitution.

It mentions race and that the government can make decisions on behalf of aboriginal people.

All The Voice will do is give the many First Nations groups a formal way of making their feelings / requests known in regards to legeslation and funding directly affecting them.

At least I think that’s what it will do. It’s a minefield out there just trying to find a simple common message that will pass a “pub test” amongst all of the NO voters at my local!

Racism is the opium of the proletariat