It is a matter of public record that for much of the past decade Ben Roberts-Smith has had a coterie of powerful men looking after his interests. Most conspicuous among them: media baron Kerry Stokes, who bankrolled Roberts-Smith’s unsuccessful defamation case against The Age, The Canberra Times and The Sydney Morning Herald for their reportage of his alleged war crimes in Afghanistan.

During the trial, Stokes called for the SAS to be “applauded and respected” and condemned “scumbag journalists” for their reporting on Roberts-Smith. All the while, Roberts-Smith remained employed at Stokes’ Seven Network.

Since Justice Anthony Besanko’s verdict, finding that on the balance of probabilities the Nine papers had established the truth of their reporting, Stokes has been joined by much of the commentariat at News Corp, who have been swift to remind their readers that the verdict did not meet the criminal standard of proof and that many in “mainstream Australia” still supported Australia’s most decorated living soldier.

Retired military figures have been wheeled out to emphasise Roberts-Smith’s “exceptional bravery”. Roberts-Smith did not attend the final days of his trial, instead sunning himself in Bali. Upon his return, he told the media that he had nothing to apologise for.

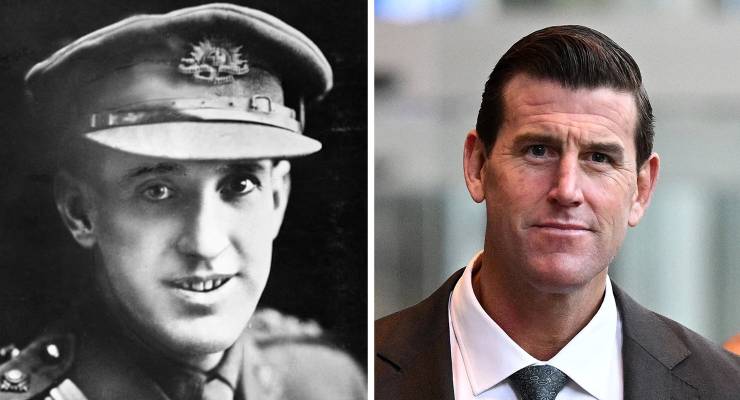

The level of institutional support behind Roberts-Smith calls to mind the very different experience of another Victoria Cross recipient who publicly fell from grace.

Like many others who served in World War I, images of Hugo Throssell — whether caught on film, on commemorative cigarette cards, or in George Lambert’s pencil line portrait — have a quietly stinging quality. The smile housed in that broad jaw is melancholy, unsure; his large clear eyes slightly spooked.

Throssell, a Western Australian premier’s son and champion boxer, was instrumental in the birth of the Anzac myth, being awarded a Victoria Cross for his “conspicuous bravery” at Gallipoli in 1915.

Hugo’s son Ric described in his memoir the adulation that engulfed his father on his return to Australia: “His exploits at Hill 60 were told and re-told with romantic embellishments.” He returned to Australia between deployments and his celebrity was put to use in an army recruiting campaign. Privately he was deeply anxious and guilty about encouraging more young men to volunteer for a war whose futile horrors he had witnessed firsthand.

He returned to Australia in late 1918 — “out of work, but never so pleased to lose a job in my life” as he put it — and married author and communist Katharine Prichard.

By this time, Gallipoli was already being solidly put to work, a senseless military calamity pupating near instantaneously into a founding national myth. Official war historian Charles Bean went so far as to say that on April 25 1915, the “consciousness of Australian nationhood was born”.

Prime minister Billy Hughes, addressing soldiers during his push for conscription during World War I, spoke of the “sweet breath of sacrifice” of the soldiers at Gallipoli, and when campaigning for reelection in 1917 attacked his former colleagues in Labor for their refusal to extend Parliament and allow the Nationalist government to attend the Imperial War Conference, thus ensuring, he argued, “The voice of Australia, this country whose sons have dyed the rocks and sand of Gallipoli and the great battlefields of France with their hearts’ blood, will be silent”.

It was amid the apparent adulation due to those who returned from that blood-soaked soil, and the legitimacy political leaders claimed on their behalf, that Throssell gave a speech at the Peace Day celebrations in his hometown of Northam in July 1919, where he announced that he was a socialist and a pacifist.

“You could have heard a pin drop,” Prichard wrote to a friend afterwards. She had not realised, her son would later write, just what this announcement would end up costing. Throssell was condemned by his family and the military establishment, both of whom blamed his new wife and ostracised him “mercilessly”.

The Commonwealth Investigation Branch (CIB), Australia’s internal security agency in the inter-war period, instantly placed Throssell and Prichard under surveillance upon its inception in WA in November 1919. A report prepared for the CIB claimed Throssell’s war injuries had “affected his mind”. His job at the Returned Soldiers’ Land Settlement Board was “dispensed with”, something Prichard always believed was down to their politics. None of this is mentioned on his Department of Veterans Affairs page.

Increasingly isolated and financially ruined, he eventually committed suicide with his service revolver in 1933. At this point, his son would later write, “the army reclaimed its hero. The Union Jack covered the Bolshevik”.

What Throssell might have given for a Kerry Stokes, or a national broadsheet, in his corner.

For anyone seeking help, Lifeline is on 13 11 14 and Beyond Blue is on 1300 22 4636. In an emergency, call 000.

I did not know about Hugo Throssell. A VC, no less. His story should be incorporated into the ‘Anzac myth’, making it more truthful and so more useful than the nonsense that’s been put about since Howard.

Hugo Throssell demonstrates what happens when you speak truth to power. The first member of my family who went to WW1 wrote home fervently ‘please do not let any of my brothers come to this place.’

My maternal grandfather fought in the Boer War. He then returned to Scotland and married. In 1911 he and his wife emigrated to Australia with their four children, the youngest of whom was my mother, 18 months old when they arrived in Melbourne in March 1912. Another son was born in Australia.

My grandfather adamantly opposed war. In WW2 neither of his sons and none of his three sons-in-law joined up and went to war. When schools had Anzac Day ceremonies my normally calm, pleasant, wise grandfather would hurrrmp fiercely against such events and the “indoctrination of children”.

I suspect Throssell and Pritchard had more supporters than is generally recognised.

I wish, without any hope of course, for a year to come when Anzac Day will be celebrated by a few old military buffs while Remembrance Day is a public holiday intended for people to spend the day musing on the futility and stupidity of war.

I read years ago of a VC recipient from WWI who shot himself after realising his wife would get a pension if he were dead. Could this be the same man after he became unemployed?

Regarding Stokes’s patronage of BRS, it is beyond my comprehension how a solider who has reached the lofty rank of corporal would have acquired the skills and experience to fill a role as General Manager in a national media organisation.

Yes you’d think so. but what it shows, rather than the limitations of skills in the ranks of NCOs like BR-S, is the definite limitations in the job requirements for the seemingly important role in senior management. How dumb do you have to be if a Corporal, one rank above Lance Corporal, can do the job that pays potentially millions. Basically if BR-S can do the job as Manager, I guess anyone can.

From what I have read, NCOs in the SAS exercise far more authority than their counterparts in regular army units – as this extract from Jonathan Huston’s December 2020 article in the ASPI Strategist explains:

Operationally, the SAS works in patrols of four to six men and there’s rarely an officer among them. This is different from the rest of the army, where an officer is almost always within 100 metres of a soldier or helicopter or truck. An SAS patrol can be isolated for weeks, save occasional radio situation reports. This is where sinister events occurred.

Exactly. There is good reason why officers are rarely detailed to these units – the politics of blame and avoidance is definitely a skill learnt and deployed against NCOs and Privates when FUBAR becomes uncontainable within a Squadron or Grunt Company Section detail. Even grunt sections can be deployed for up to 10-14 days on specialist operations without company or Battalion support in combat.

A 100 years on and Charles Bean’s utter drivel and dross rains down still.

The indestructible Anzac myth is due largely to his sentimental yet nasty racialised, classist moralising and exaggeration. The legend of the indomitable bush-reared digger, born from the scribblings of a reactionary imperialistic waffling obscurantist parochial partisan.

And he was a Pom. Then again so were a quarter of the Anzacs.

CEW Bean was not a Pom. He was born in Bathurst NSW in 1879.

The Australian War Memorial was his idea. The original intent was to have a place for reflection on the appalling consequences of war. That endured until the last decade when Nelson, Abbott and Stokes, all AWM Board members at various times, decided to pull down a quite lovely (and the recipient of an architecture award) memorial building and replace it with a war toys theme park at the vast cost of $500,000,000 plus some extra thrown in by the departing Lib government to cover increased building costs.

Yes, true, but his family did move to England when he was ten and he didn’t return until he was in his twenties, armed with an Oxford degree. He also thought of himself as a new chum.

Yes and the $500M has made it a mega embarrassment

Testimony to those AWM board members

Once a sacred memorial now an war orgy den

Thank you for your service

I have long been interested in military history, partly due to a photo on my grandma’s mantlepiece of five young pilots out front of a tiger moth. It is also in the AWM collection. Only two came home. Of the dead, one was Rawdon Middleton VC a man whose endurance of pain and horro was remarkable. What was also remarkable was the change in his face from the dashing young man with the moustache who claimed the heart of one of my aunts to the haunted, apparently middle aged, face of the man who died two years later. He was 26. I have read very few first hands accounts by VC winners of the events at hand, but many accounts by others. What impressed me, and perhaps alarmed me, about Roberts-Smith’s account in wartime was the complete clinical coldness of it. My daughter worked at the AWM for 10 years before deciding that the theme park that Brendan Nelson (and Kerry Stokes BTW) were creating had taking the soul of the place. I said to her then that I thought BRS was an extremely dangerous man. It seems I was right.

I just read a description of his final flight. A true hero.

The RAAF base I worked in during the late 60’s had a Middleton Street. There is a Middleton Avenue in Point Cook.

Your daughter is right on the mark! “THE SOUL OF THE PLACE”. I remember the 2019 Anzac Ceremony across the road here in Kelmscott WA before Covid hit. Wonderful crowd, tears shed, kookaburras singing in the trees with the sun rising and here we all were at our little monument in the corner of our park. I reckon about 300 of us. So there you go. Even I was stunned at the amount of people, especially the young families.