I will forever remember choking on my morning coffee when I read The Age on June 8 2018. Nick McKenzie and Chris Masters’ article detailing the alleged war crimes in Afghanistan of a highly decorated Australian war hero was confronting, to say the least. “This is crazy brave,” I remember thinking. “I really hope they’ve done their homework.”

Unsurprisingly, they had. I say unsurprisingly given Masters comes from the golden age of Australian investigative journalism in the 1980s; his seminal reporting of corruption in Queensland exposed the rot in the Joh Bjelke-Petersen government and eventually brought it down.

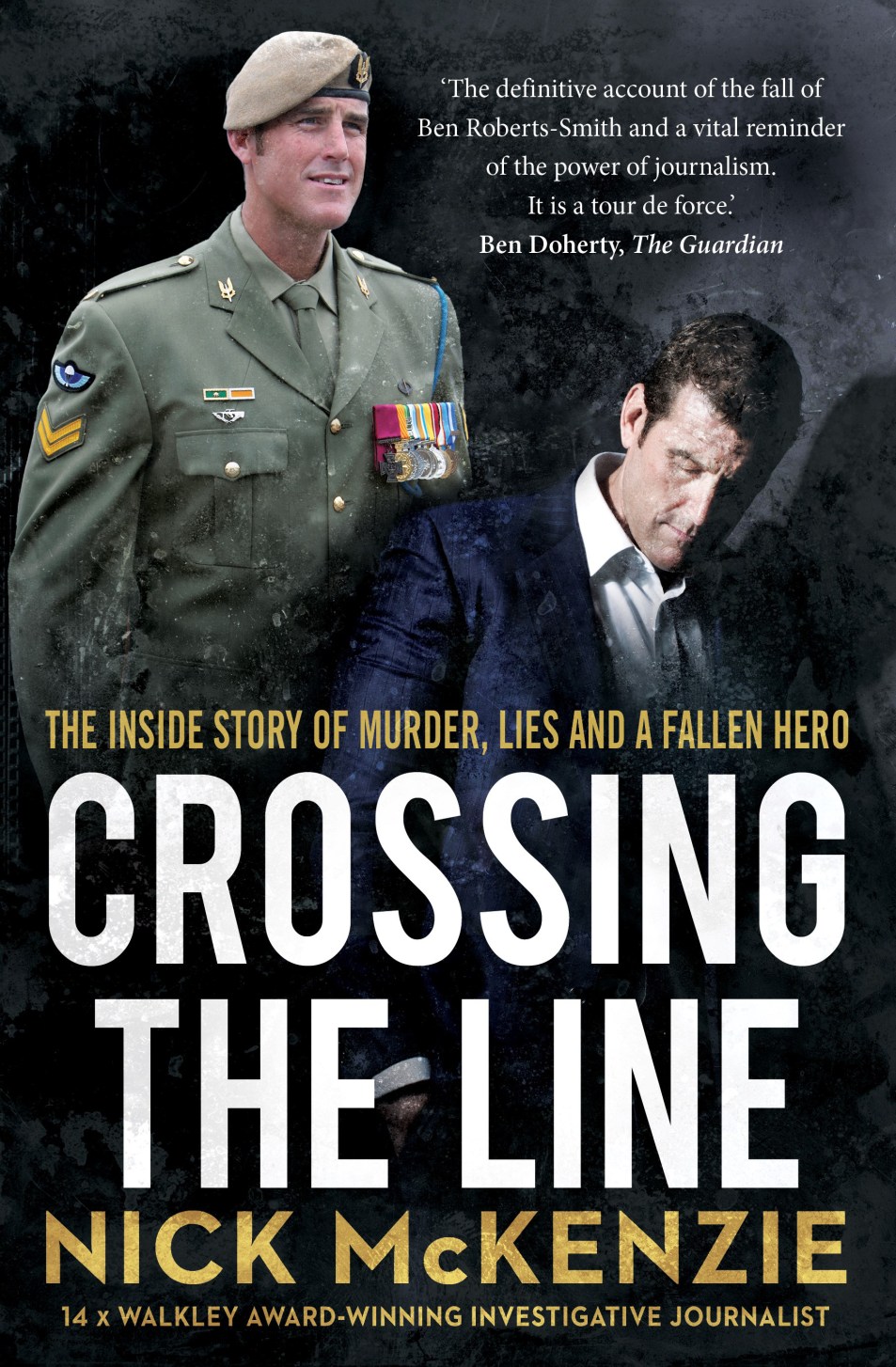

The opening of McKenzie’s book, Crossing the Line: The inside story of murder, lies and a fallen hero, makes one reflect on how Australian investigative journalism manages to thrive, making crucial contributions to our liberal democracy and holding societal powers to account.

To list a few of the past decade: McKenzie and team reporting on Melbourne’s Crown Casino; ABC’s Four Corners and Louise Milligan reporting on child abuse in the Catholic Church leading to the royal commission into institutional child abuse; Crikey’s Amber Schultz reporting on the abuse of state guardianship; Nine’s Adele Ferguson exposing malpractice in the banking and financial sector regarding financial advisory services.

These examples are even more impressive given the severe restrictions on public interest and investigative reportage in Australia, where power elites employ “lawfare” to smother public interest journalism.

However, McKenzie’s and Masters’ reporting efforts on Ben Roberts-Smith go beyond any previous investigative undertaking in Australia. McKenzie’s book, in forensic detail, tells the inside story of the Roberts-Smith reporting project, reflecting the courage required to shed light on the nation-forming myth of the Anzac legend and Australia’s infatuation with war heroes.

To dare to question the reputation of a living war hero is one of the greatest challenges in public interest journalism in Australia. We should all be deeply grateful to McKenzie and Masters for igniting a much-needed, respectful national discourse on our relationship with the Anzac legend. This relationship is far from healthy, as McKenzie’s book so clearly and eloquently illustrates.

Crossing the Line resonates strongly with me. I have deployed twice with UN peacekeeping forces in Cyprus and Lebanon, and although I’ve never witnessed the alleged savagery of Roberts-Smith and some of his colleagues, I have seen his archetypes — the bullying, the lack of empathy, the harm caused to those deployed too many times into theatres of war.

The book outlines in detail how sections of the Australian power elite tried to stop the truth from being reported, including: Brendan Nelson, the former defence minister and former director of the Australian War Memorial; Kerry Stokes, the Seven West Media billionaire who bankrolled Roberts-Smith’s defamation case to the tune of tens of millions for dollars; and, disappointingly, decorated investigative journalist Ross Coulthart, who was allegedly hired as a PR consultant to pressure The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald to not run the stories.

Roberts-Smith’s defenders corralled around him, knowing the Australian Defence Force-instigated Brereton inquiry into alleged war crimes in Afghanistan was ongoing. Surely this should have sparked some doubt in their support for the disgraced war hero, especially given the number of current and former SAS soldiers — including former SAS captain and current Liberal member in the House of Representatives Andrew Hastie — who spoke up about the problematic culture in the SAS.

I know from personal experience how incredibly strong the code of silence is within special forces units. The fact that McKenzie and Masters, from the first article, had numerous SAS sources indicated they were reporting the truth and had done due diligence in ensuring they could back these deeply serious claims.

Whatever happens next to Roberts-Smith (and this case still has a long way to run), the power elite that backed him and tried to stifle the truth should be held to account. Perhaps this will happen with each indictment we are bound to get from the office of the special investigator acting on the Brereton report, which found there was credible evidence of 25 Australian soldiers being involved in 39 murders of Afghans during their deployments to Afghanistan.

The current chair of the Australian War Memorial, Kim Beazley, has a major challenge in how the memorial deals with disgraced war heroes, starting with the life-sized Roberts-Smith portrait and exhibition.

The book is a complete page-turner and a master class in investigative journalism. Tracking down the name of the victim kicked off a cliff and then shot in the Darwan incident is crucial in humanising a killed Afghan civilian. His name was Ali Jan. The section where McKenzie describes his trip to Afghanistan to talk to Jan’s wife, Bibi, is deeply moving.

Echoing McKenzie’s words, we owe an immense debt to the SAS soldiers past and present who stood up and told the truth. They are the real heroes. As Hastie pointed out, they may have saved the SAS.

With McKenzie and Masters (and credit to both Fairfax Ltd and Nine Entertainment for backing the publications), they managed what no other liberal democracy has done to this extent so far: expose the dirty and disgusting underbelly of war, which morally corrupts some of the people we deploy to fight in our name.

McKenzie’s book should be read by every Australian. It will certainly be a set reading in the journalism courses I teach.

Give a brute a uniform, a badge and a vast array of guns – what could possibly go wrong?

Ben Roberts-Smith, and his criminal mates in the SAS, have had their criminality exposed in the Brereton Inquiry. In addition, he stands condemned by another judge who decided that, on the balance of probability, he committed terrible war crimes. And yet he remains free, to walk among us, still not charged with any wrongdoing at all. A murderer who, it appears, will never face justice. What the hell is going on here?

Today in the Federal Court the Commonwealth asked for access to evidence presented in Roberts-Smith’s civil defamation trial to use in ongoing war crimes investigations. So the show isn’t over yet for BRS.

Today in the Federal Court the Commonwealth asked for access to evidence presented in the civil defamation trial to use in ongoing investigations. So the show isn’t over yet.

He’s rich (or in their milieu) – no accountability any more, haven’t you heard?

You’d have to be deaf and blind to have missed the memo from the UK Tories…

Lets not forget barrister Arthur Moses (aka Boo, aka The Count) who was paid stupid amounts of money and put his reputation on the line to defend this immorale t-rd. His reputation must be in tatters now. I’m sure Gladys will warm him with a hot cuppa.

Are you saying that some defendants, because of the allegations they face, are not entitled to representation, so any barrister that appears for them is tainted? Or are you saying Arthur Moses’ reputation is in tatters simply because, in your view, he did such a rotten job compared to what you’d expect from a competent barrister?

Incidentally, in the relevant court case Ben Roberts-Smith was not a defendant and he was not being defended by Arthur Moses or anyone else. He was the plaintiff, sueing for damages.

Hard disagree. For our adversarial legal system to function all parties are entitled to competent representation.

That BRS spent around 15 years in the army, was touted as a fine leader, yet could only manage the rank of corporal after all that time, should speak volumes as to the quality of the man.

The leadership potential of corporals? A century ago there was an Austrian in the German Army who only achieved the rank of corporal (along with an Iron Cross 1st class, a rare award for an NCO), but he went on to be rather well-known leader.

That is true, Sinking SR. But it has been remarked upon, perhaps in an extract from McKenzie’s book, or another piece recently published, that BR-S underwent something of a transformation (middling student, chubby average soldier, to buff, muscled SAS, ‘absent, indifferent husband/father, to father of the year’), etc, but his failure to progress beyond cpl suggested the hierarchy knew something was up. OTOH, the structure of the SAS is such that leadership is devolved because it’s the patrol leaders that take the blokes out, and they like to keep the officers back at base.

Also worth noting, and recently reported in the Nine papers, the toll exacted upon sociologist and researcher Samantha Crompvoets who has lost her livelihood as a result of exposing the crimes and misdemeanours in the SAS and armed forces. We owe *her* a great debt, and something should be done to restore her working life and reputation.

The cat’s out of the bag for her – as she says, most organisations hire consultants to tell them what they want to hear, and her frank and fearless runs are on the board.