Well, that’s interesting, I thought when I read this statement published by the ABC last week:

A recent court ruling would have forced the ABC and our journalists to reveal the confidential name of a key source in the defamation matter being brought by former serviceman Heston Russell … The ABC had no choice but to uphold its commitment [to protect its source] and abandon its defence of proceedings.

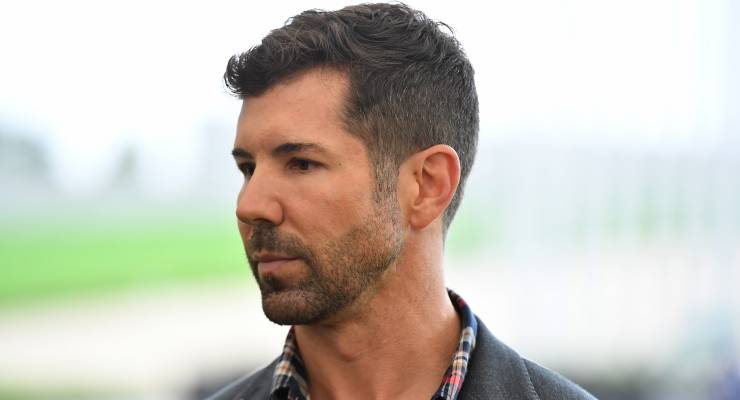

Russell, a former special forces member who served in Afghanistan, is suing the ABC in the Federal Court for defamation over two stories it published in 2020 and 2021. The court has already ruled that he was defamed — most seriously, by being accused of taking part in the alleged murder of an Afghan civilian — so the only question is whether the ABC has a viable defence.

The situation as publicly presented by the ABC was one of Hobson’s choice: because the court had backed the broadcaster into a corner, it could not defend its reporting without breaching its commitment to protect its source’s identity. Therefore, it was really no choice at all.

The logical extension of that dilemma is that any time a media publisher runs allegations of wrongdoing against an individual based on information received from a confidential source, it won’t be able to defend itself in court because the source will be revealed. That sounds like a comprehensive snookering of investigative journalism.

However, the ABC left two important pieces of information out of its cry of victimhood. First, there’s the small issue that the identity of its source in the Russell story wasn’t confidential at all. Everyone knew who he was. The ABC had broadcast his face and voice, undisguised, and revealed other identifying information in material submitted to the court. Russell’s lawyers, and his media barrackers, had worked out the guy’s name easily enough.

All this bemused and frustrated the judge, Justice Michael Lee, who said, “This is developing into a bit of a farce”. He told the parties he would no longer be compelling the ABC to identify its source, since they all already knew who it was.

That happened after the ABC had published its statement, but it must have seen what was coming. Equally mystifying, the ABC then reversed course completely, reinstituting the defence it had been insisting it was forced to abandon. That will now go to trial. So, what was the point of the public hissy fit?

The second piece of information the ABC neglected to mention is that its dilemma — which it insisted presented an existential threat to public interest journalism — is neither exceptional nor difficult to resolve.

Obviously, a great deal of what gets published and broadcast by the media is heavily dependent on unnamed sources. Journalists are famously protective of those sources; they simply don’t reveal them, on pain of death. Our shield laws are feeble, meaning that pain is a real threat, yet somehow the business keeps running.

When circumstances do arise where the law insists that the disclosure of a source takes higher priority than a journalist’s ethics, the system offers mechanisms for that to occur. Most powerfully, the courts possess almost limitless powers to protect the confidentiality of information. These include suppression orders, closed courts, concealment of witnesses and so on. Whatever is necessary to ensure that something secret doesn’t get out, a judge can make happen.

If it was essential in the ABC’s defence of Russell’s case for its source’s identity to be disclosed to Russell’s lawyers — as a matter of fairness, to enable Russell to properly counter that defence (and I can understand how that might be) — then that could have been facilitated by an appropriate suppression regime. That could even have included the identity being kept from Russell himself, if that was an issue.

That being so, it’s difficult to understand what the ABC thought it was complaining about. Sure, any disclosure of a source, even under compulsion and in carefully protected circumstances, would be a compromise of a journalist’s promise. However, it has always been a fact that no journalist could offer the promise without any qualification, and the Russell case is one example that demonstrates why.

It’s tempting to conclude that the ABC has found itself defending a losing case and was seeking cover for the anticipated disaster. If so, it failed in that endeavour as well.

Thanks for explaining the relevant facts regarding protection of sources in this case – which not covered in the MSM as far as I know.

This was covered quite extensively on Media Watch on Monday. Worth a look.

I hope Heston wins a big sum from the ABC, an apology would be delightful too.

So our defamation regime is so weird that Russell may succeed in proving he was defamed for something that may be subsequently proved in criminal proceedings that he actually did. This is madness.

It is only after defamation is established that defences kick in. So he has to establish that he was defamed, then the ABC can plead truth or public interest. But yes, defo law in Australia is not as good as it could be.