Because of the climate crisis, governments shouldn’t be approving new coalmines. Doesn’t seem like a controversial thing to say, does it? At the Australia Institute, we’ve been saying it since at least 2015.

Yet eight years later, we still get social media “experts” and the occasional piece here in Crikey breaking the news that coal gets used to — drumroll — make steel.

This is, of course, correct. Coal gets used for two main things: generating electricity and making steel. Our old friends at the Minerals Council have a good explainer, but here’s what happens in a nutshell:

- Electricity: coal is burned to heat water into steam. The steam turns a turbine, generating electricity.

- Steel: coal is subjected to very high temperatures and turned into a near-pure carbon product called coke. Coke gets burned in a furnace with iron ore to achieve very high temperatures, creating a liquid metal and removing oxygen from the iron ore. This is important for strengthening steel.

Renewable energy is already replacing coal for electricity generation, but the decarbonisation of steel is less advanced. Because of this, our critics suggest, we should lay off new metallurgical coal mines.

This is wrong. Let’s examine the ways.

The climate doesn’t care

All kinds of coal are fossilised carbon that has been safely stored underground for millions of years. Digging up and burning it means that it will enter the atmosphere and contribute to climate change.

Enough already!

Australia supplies 61% of the world’s traded metallurgical coal and Queensland’s existing mines have huge reserves that will last for a long time. BHP claims its mines will operate for decades — Saraji has approval to 2044, Caval Ridge to 2056 and Peak Downs is currently applying to extend until, wait for it, the year 2119.

It’s not easy being green steel

Or at least it is not yet cheap. Greener approaches to steel exist, like electric arc furnaces and the replacement of coal in blast furnaces with hydrogen and other chemicals. This is already happening; Sweden is going hard at it. But it doesn’t help when a significant supplier like Australia expands its metallurgical coal supply, making dirty steelmaking cheaper and reducing incentives to switch to cleaner methods.

Coal doesn’t come pre-sorted

Coal doesn’t emerge from the ground in batches neatly labelled “metallurgical” and “thermal”. It has a range of properties such as moisture, carbon content, coking properties, ash content (junk), etc, and these specifications vary between mines and even between different parts of the same mine. As a result, most coal mines dig up some coal that is sold as thermal coal and some that is sold for steelmaking.

There are few mines that see 100% of their production used to make steel. According to Queensland government statistics, the state has 63 coalmines that have operated between 2015 and 2021. Only 16 claim to have produced 100% metallurgical coal, and a further 11 over 90%. Similar statistics aren’t available for NSW, but it is unlikely that any mines in the state, and certainly not in the Hunter Valley or northwest of the state, produce only steelmaking coal.

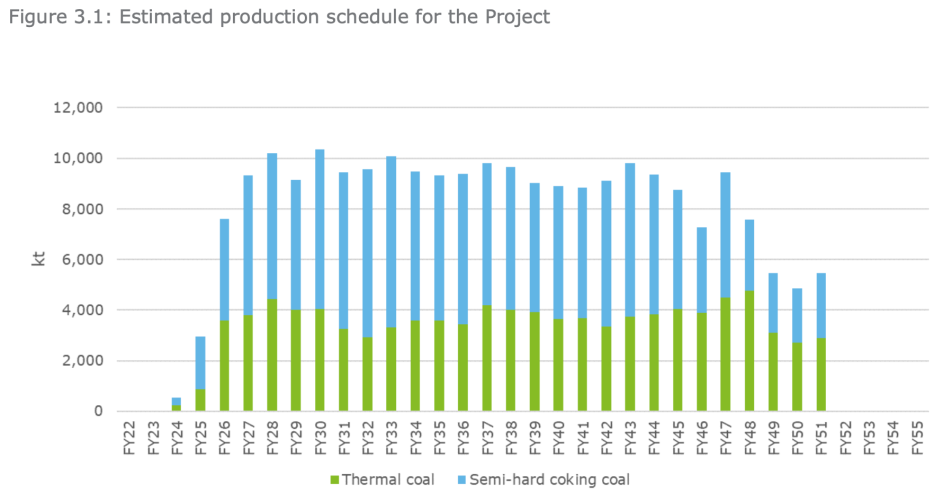

Often mines are presented as being only coking coal, when in fact they produce large amounts of thermal coal. For example, in the media and according to lobbyists, Whitehaven’s Winchester proposal in Queensland is “for steel production”, and is expected to “produce up to 11 million tonnes per annum of primarily high-quality metallurgical coal for steel manufacturing over a 30-year mine life”.

But when you look up the finer details, almost half of its production is thermal coal:

Who would have thought that coal lobbyists might be loose with the details, particularly as banks are becoming reluctant to lend money to thermal coal mines?

As the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis puts it:

Australian thermal coalmine developers often suggest that a percentage of their proposed product will be sold as [metallurgical] coal, despite there being no certainty that any output from a proposed mine will be sold into the metallurgical coal market.

With an increasing number of banks and other financial institutions ending their financing of thermal coal, it is useful to thermal coal miners to suggest that new mine developments will produce metallurgical, as well as thermal, coal

Staying with our Winchester example above, not only would this “metallurgical coalmine” actually produce large volumes of thermal coal, but the metallurgical coal it would produce is “semi-hard”, which means it is only “semi-good”. Many Australian mines, particularly in NSW, produce “semi-soft” coking coal, which is lower grade still.

An even lower grade of metallurgical coal is pulverised coal injection (PCI) coal, which, to quote the Minerals Council, is “basically high-quality thermal coal”. Despite this, plenty of mines that only produce PCI are spun as exclusively steelmaking mines.

PCI can be used for steelmaking and doing so is “significantly cheaper than coke and is therefore an economical replacement for coke” (still Minerals Council). The problem is that PCI is potentially displacing the high-quality coking coals that the Minerals Council likes to claim “maximise productivity and reduce the amount of CO2 produced”. To spell it out: some Australian metallurgical coal is very low grade and is used to displace higher grade (possibly Australian) coal, making steelmaking dirtier.

If Australian governments, industry and their supporters were serious about climate change and steel supply, there is plenty they could do. They could specify that Australia’s coal exports only be used for steelmaking, just as they specify that the country’s uranium is only to be used for peaceful purposes.

Better still, they could reduce demand for steel. Modern wooden buildings, which can be more than 100 metres high, use almost no steel. Serious investment in public and passive transport would reduce the number of cars bought, one of the key markets for steel.

And, of course, they could place a moratorium on new coalmines. Not on thermal coalmines, not on semi-something coalmines. No. New. Coalmines.

Thanks Rod. You are providing plenty of return on my support for The Australia Institute.

Thanks Barnino!

Ditto- keep up the good work!

Good article. I was in favour of metallurgical coal until I read it. Now, I’m taking everything under advisement.

Thanks, Frank.

Can’t argue with the points you make, but it’s the point which you don’t touch on which bears comment.

It is the presence of carbon (maybe 1% worth) which converts iron to steel and gives steel all the better properties which make it useful. If we are going to need an increased amount of steel over time, from whence does the carbon come? Presently, pretty much all carbon-based materials (which include metallurgical coke, plastics and rubber) come from fossil-based sources, either oil or coal.

The key challenge is to come up with alternative source of carbon for use in industrial processes to make useful materials. Recycling has a role to play, but it won’t get us all the way there. Anything made of steel is expected last some time, and it can’t just be pulled down next year or next decade for the purpose of making new steel.

Perhaps your next article can address this point. Don’t mention plant-based material because we need to feed the world and retain our forests as carbon sinks.

Thanks Paul, far from my expertise, but the main green steel problem AFAIK is not getting carbon into the steel, but getting the oxygen out of the iron ore. That and heat is what Coke is for. Will look into it.

Hi Paul,

As you suggest, even high grade steel is about 1% carbon. That’s not much. It doesn’t have to come from coking coal. I’ve heard of a project somewhere using old tyres as a source. Regardless, it’s a non-issue.

It’s the coking coal which has to go. As Rod indicated, there are alternatives to that, but they aren’t yet happening at scale. But as long as we keep supplying cheap coking coal, that won’t change.

Another important aspect to this is recycling. Already, about 40% of the world’s steel output comes from recycling – impressive, but could easily be much greater. (And this is genuine recycling – can be done multiple times – unlike plastic, say)

Another topic is what we do with all the steel we produce – not just housing and hospitals, but cruise ships, planes and armaments.

And a final important but whole new topic is growth versus degrowth – maybe best left for another day.

Good article, if we prohibit new mines in Australia for coal export it is nice to know other countries will follow suit. We can join Ireland, Spain, Belize and Denmark in banning fossil fuel exports. It is highly unlikely that countries like Indonesia or Brazil would step in and replace Australian coal exports, it’s not as if they did so when China’s unofficial ban on coal from Australia was in place.

We are the preferred supplier of coking coal in the region because it’s high quality and cheap. If we don’t expand, we limit our exports, and the global price will go up. That’s a good thing surely?

I’d love to see a carbon tax on third order emissions, the ones that customers generate when using our minerals. That would push poor quality mines to close more quickly and reduce the investment case for new mines.

I reckon ‘We’ may have been able to continue using coal in ‘moderation’ well into a gradual phasing-out future, were it not for the fact that governments have placed all our power needs in the nests of fossil fuel donors, for a ‘consideration’ of policy in return, for way too long. Half a century ago or so, there could have been a concerted effort to push into diversifying into alternate renewable sources to supplement needs as need grew greater to eventually take over – but that would have meant those donors losing some of their huge profits (from which to donate) so there was no way that was going to happen at government level if they could help.

So here we are now – that dependence on those fossils now means we can’t afford it at any cost now. There’s a bigger picture to fry.

Short-sighted short-term interests has won, over long term bigger picture prospects, again (depending on who you’re backing of coure). And who’s paying …. again?