Much of Australia will dodge a black summer this year, but large swaths of the country will still burn, new analysis reveals.

“If you have fuel, fire, wind speeds and warm temperatures, you will get bushfires,” Rob Webb, CEO of the National Council for fire and emergency services (AFAC), told Crikey.

Today AFAC released its seasonal bushfire outlook for spring. The state-by-state and territory-by-territory forecasts, based on intel from local fire authorities, are expected to set the tone for the nation’s 2023-24 summer season of fires.

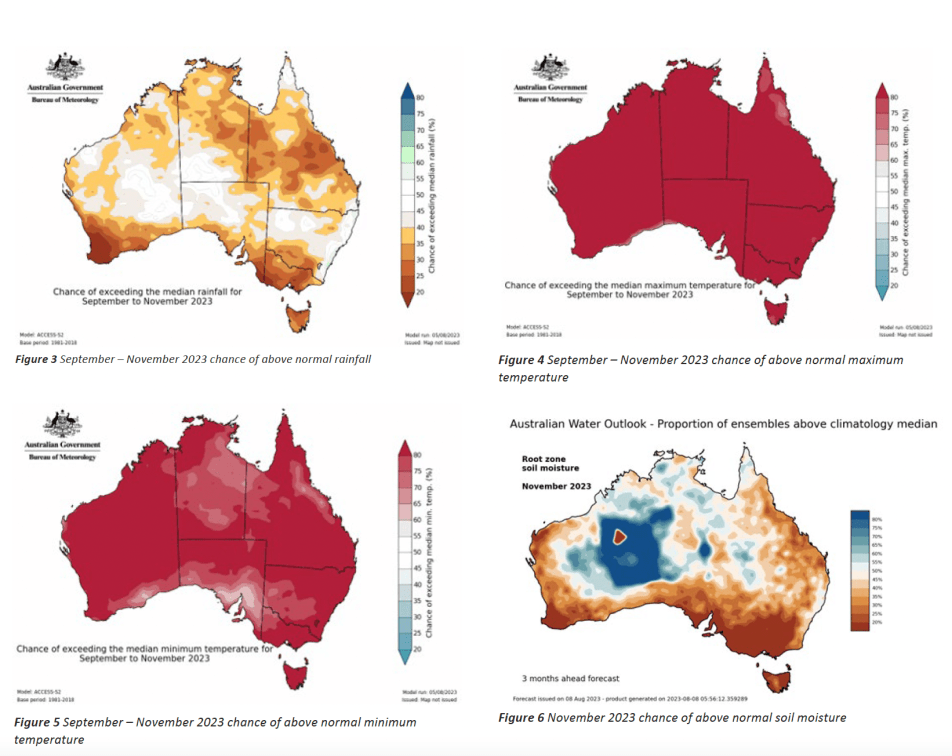

Webb said the nation’s coming bushfire season will be worse than the three wet summers past, but not on a par with the catastrophic 2019-20 summer that devastated south-east states. In short: above-average rainfall has stimulated grass and groundcover growth, but a rapid swing into hot and dry conditions is making all this excess fuel ripe to burn.

“We’ve had three years of wet conditions, and while that’s dampened the earth, it’s also led to grass growth that’s fast drying out,” he said. “That means we’re mindful of fast-moving grassfires.”

Nominated high-risk areas include the Northern Territory, Queensland, NSW and smaller regions in Victoria and South Australia.

Earlier this month, NT authorities projected that 80% of the territory would burn by the end of March 2024. CEO of the Central Land Council (CLC) Les Turner said it was unlikely the scale of burning would eventuate, but he credits this year’s fire-friendly conditions to excessive rainfall that’s shortened the prescribed burning season and encouraged growth of the invasive and highly flammable weed buffel grass.

“[Buffel] has accumulated with the past three years of high summer rainfall and will grow back very quickly after it’s burnt. This means that native plants don’t have a chance to recover and go to seed before the next fire, leading to a slow decline in the number of large trees,” he told Crikey.

“Rivers and creeks used to be good firebreaks because they didn’t have grasses that burnt easily. Now, with buffel, they’re full of fuel and carry fires further instead of stopping them.”

Turner said wet conditions, often preceded by hot weather, have dramatically reduced the window of opportunity for Indigenous peoples to properly burn country: “They know the right time to burn to protect natural and cultural assets and prevent large fires. A lack of people on country in remote central Australia means that the country’s not being managed as it always has, leading to hot landscape-scale fires.”

In the years since the devastating 2011-12 bushfires that wiped out 80% of the territory, Turner said land management had improved, particularly with the use of prescribed aerial burning in the cool season. In June this year and last year, Warlpiri, North Tanami and Tennant Creek CLC rangers, in partnership with the Indigenous Desert Alliance, used planes to burn more than 6000 square kilometres.

A spokesperson for the NT Environment, Parks and Water Security Department told Crikey the department had also conducted fuel-reduction burns and clearing, particularly around assets, but excess fuel loads had been difficult to manage due to high moisture levels in soil.

Despite the 3000-plus bushfires between June and August in urban and peri-urban areas of the Northern Savanna, Arnhem and Top End regions, it’s business as usual for these parts going into spring and summer. The AFAC report said that was due to fire scars and carbon abatement programs that mimic “mosaic-style fire scar coverage”.

The problem areas for the NT (and regions most at risk across Australia) are the Barkly, Lassiter, Simpson and Alice Springs districts.

“Every time there’s been an extended period of high rainfall in the past, such as 1974, 2000, 2011, there have been fires throughout central Australia,” Turner said.

In South Australia, deputy chief officer Georgie Cornish said her state had also seen considerable drying out of fuel above ground and under the soil, particularly in the Nullarbor (south-west) and Mallee Heath areas (south-east approaching the Victorian border).

“We’ve seen the ground really dry out and what that means is the soil simply won’t have moisture in it,” Cornish told Crikey. “That means those areas catch really easily.”

Cornish said that unlike NSW and Queensland where fire scars pose a reburn risk, SA’s burn cycle was approximately seven years due to the oil content of the low-lying shrub mallee heath, which burnt on masse during SA’s 2019-20 season.

However, SA is facing an increased risk of grassfires compared with other states due to the excess plantation of wheat crops. Cornish said the Ukrainian-induced wheat crisis has prompted farmers to boost their yields as prices were up. The result was “more continuous crops” that were more susceptible to fast-moving grassfires.

In the eastern states, fuel loads were ripe for fires, but none were expected to tip into extreme territory this bushfire season.

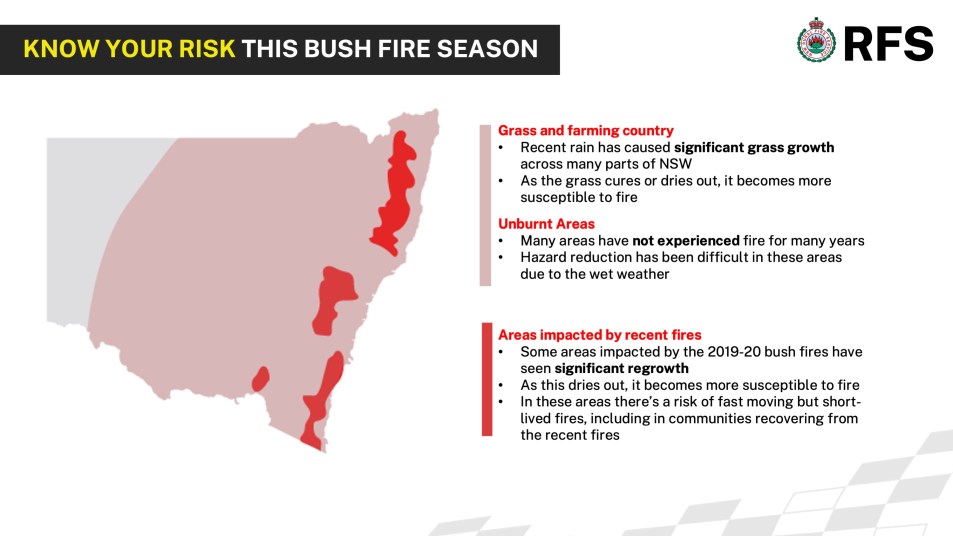

NSW Rural Fire service inspector Ben Shepherd said his state would also be on high alert in regions with excessive grass growth (particularly west of the divide and throughout the Hunter). Other priority regions were areas that had not recently burnt, where fuel loads are high (including the central coast, in and around Sydney, down through the Illawarra, and parts of the Shoalhaven) and “fire scars” from 2019-20 where regrowth had altered vegetation and increased fire susceptibility (mid, north, and south coasts).

Already the state had seen a dramatic rise in bush, grass and scrub fires — this July registered 1300 fires compared with 300 in the same period last year.

“There’s a lot of scrub and heath that has grown back, while the canopy and treetops haven’t repaired themselves,” Shepherd said. “Given the right conditions on a hot, windy day, we could see some very turbo fires, although not necessarily long-lived.”

It’s a similar story in Queensland, where superintendent James Hague said fires were starting to pop up — particularly in the southern half of the state — due to below-average rainfall and a westerly wind that lowers humidity: “Westerly winds herald more fire weather.”

Hague said significant rainfall in central and northern parts of the state throughout the winter months had kept fires at bay, however, if these areas began to dry out, the risk of wildfire would increase.

Victoria was one of the few states bracing for forest fires, particularly in unburnt bushland surrounding coastal communities. Authorities were also closely watching agricultural zones in the central, western and northern parts of the state for early-onset burns. Overall, Webb said the 2023-24 fire season wouldn’t be “record-breaking” — with fire agencies anticipating 2024-25 to be much worse — but he reiterated that a high likelihood of El Niño meant the “dial is flipping back away from widespread flooding”.

I was travelling from Newcastle to Coffs Harbour last Friday and was almost incinerated by tweets doing hazard reduction burns. I counted three hazard reduction burns that were out of control, what idiots in this chain of pyromaniacs thinks it’s a good idea to do hazard reduction burns with forecasted wind gusts of between 60-70 kph, the same idiots who will probably be responsible for hazard reduction burns during the forecasted hot weather for both the coming spring and summer which will no doubt again lead to loss of life and property. Out of control hazard burns at Cundletown, western side of Pacific Highway near Port Macquarie, and the hazard reduction burn that almost toasted me and many other trapped motorists on the Pacific Highway, 10 kms South of the Stuart Point turn-off, what a bunch of negligent trds. There was considerable panic amongst the many trapped motorists, I saw cars recklessly reversing back along the highway and then crashing through the centre vegetated culvert, people certainly lost their sht. We were stuck for at least an hour, I struck up conversations with several stopped motorists near me, all of whom were visibly stirred. I particular was concerned for the wellbeing of a lady in front of me who was on her way back to Stuarts Point, earlier in the day she had a chemotherapy infusion that had lasted several hours and she was tiring rapidly because of this balls up, thankfully she was travelling with a very caring and considerate friend who certainly was weighing up escape options. Anyway, the fire and police reinforcements arrived after the fire had jumped across the highway a short distance ahead of us, and by the time the highway was reopened, and I drove through where the fire had crossed, observing the considerable distance it had covered since, I thought, if the level of incompetence and winter combustibility is this bad now we are certainly going to cook come the long, hot, dry summer ahead. I gulped down the last remaining mouthfuls of my trusty h2o bottled water and sighed, and with absolute certainty declared to myself we are surely fkd.

Basically our new bushfire ‘season’ is August to June.

Yay for Winter.

the first map, “AFAC Seasonal Bushfire Outlook – Spring 2023” raises the question: What is WA doing that prevents increased fire-risks from crossing its border?

AFAC hasn’t heard of WA or Tas. WA has the world’s biggest temperate forest, and it burns extremely well – but nobody notices. WA is supplied by a single rail line and a single sealed road from the ES, and weather events like floods and fires regularly cut us off. I think it is so that, in the event of being invaded by the Indons, we can be isolated by one man with two sticks of dynamite. National Security is at stake.

And I hadn’t heard of AFAC until today, so we’re even.

@roberto I’m a little confused at conclusions you’ve drawn. Both jurisdictions are well represented and leverage the collective knowledge of AFAC. Those of us actively involved in preparing prevention, preparation, response and recovery for disasters / emergencies regularly support each other as needs arise. Many of us are gathered in Brisbane this week at the AFAC conference sharing experiences and learnings. While I haven’t heard of you before now, I’m humble enough to be willing to respectfully learn more. https://www.afac.com.au/auxiliary/about

Thanks for the correction and chastisement of my ignorance (which is legendary!). Seeing the map of AFAC’s fire predictions fired up my chronic slight annoyance at the Eastern States’ prediliction for disregarding WA’s existence and, to a lesser extent, Tasmania’s. This general disregard has nothing to do with AFAC, and I should not have conflated the two issues. AFAC is a body I probably should have heard of before now, whereas there is no reason you should have heard of me, so that comment I take as wry humour, rather than sarcasm (the problem with these comments is the ease of misunderstanding).

Here in WA we are very greatly supplied for our daily needs from the Eastern States, often from China via the Port of Melbourne. I remember a time last year when there was a minor flood (information was not given as to detail) that washed out a railway bridge somewhere, and that stopped delivery for the two thirds of products which come by rail, to the point that supermarket shelves were mostly empty for about six weeks, as I remember. The shortfall could not be filled by trucks across the Nullarbor as, in these events, trucks cannot appear from thin air. A similar event was the summer before when a bushfire stopped traffic on the Eyre Hwy for two weeks(!) after two truck drivers were killed. They had been waved through by the person in charge who was unaware that modern trucks have gearboxes that shut the engine down when they reach a certain temperature. After that, no risks were taken. But, again, supply to WA was interrupted because we have such limited means of supply – one road, one single rail line. Both of the incidents would have been inconsequential in any of the Eastern States, where there are usually many options for detours. Our Kimberley region is another case in point where the destruction of one bridge, by flooding, led to major disruptions to every walk of life up there quite recently. With climate change (no doubt discussed by AFAC) these events are certain to become more frequent, yet we continue to have policies of reaction instead of looking ahead and building around what will probably, or almost certainly, happen. However, I do note that bush has been cleared along roadsides, at least in National Parks where the one road out is key. Further on the rail situation: the single line takes traffic east on one day and west the next. How comic! It’s like a toy train set, where the child has only enough track for one line.

My apologies for appearing to decry the activities of an organisation I was ignorant of, truly, I meant no disrespect. I haved lived in Sydney, Brisbane and Townsville in the past, and was in the army for a while where people are thrown together from all over. So I’m reasonably familiar with the lack of knowledge of WA over there. It’s not so very long ago that the final stretch of the Eyre Highway was sealed. I’m aware that the Outback Hwy, as it will be called, is being sealed, but that will be a long way around – Melbourne to Perth via Alice Springs – and does nothing, of course, for the shortcomings of rail. Prevention of emergencies is generally cost effective in the long run. And it is a very long run over to WA, not to mention the long runs within the State. We here are frequently told by our politicians that we subsidise the rest of Australia, even ‘keeping it afloat!’ (true with the GST share at least). But, rhetoric aside, we are a third of the country – as we see it.

Go AFAC!

To sit by the Eyre Hwy and count the trucks per hour, or camp by the railway at Rawlinna and watch the wagons roll slowly through at night – high speed it ain’t – is an eye-opener.

We charge protestors, it is easier for our elected politicians