Disgraced consultancy PwC’s “Indigenous Consulting” arm — which has been given more than $44 million in federal government contracts — is owned by just two people other than PwC itself.

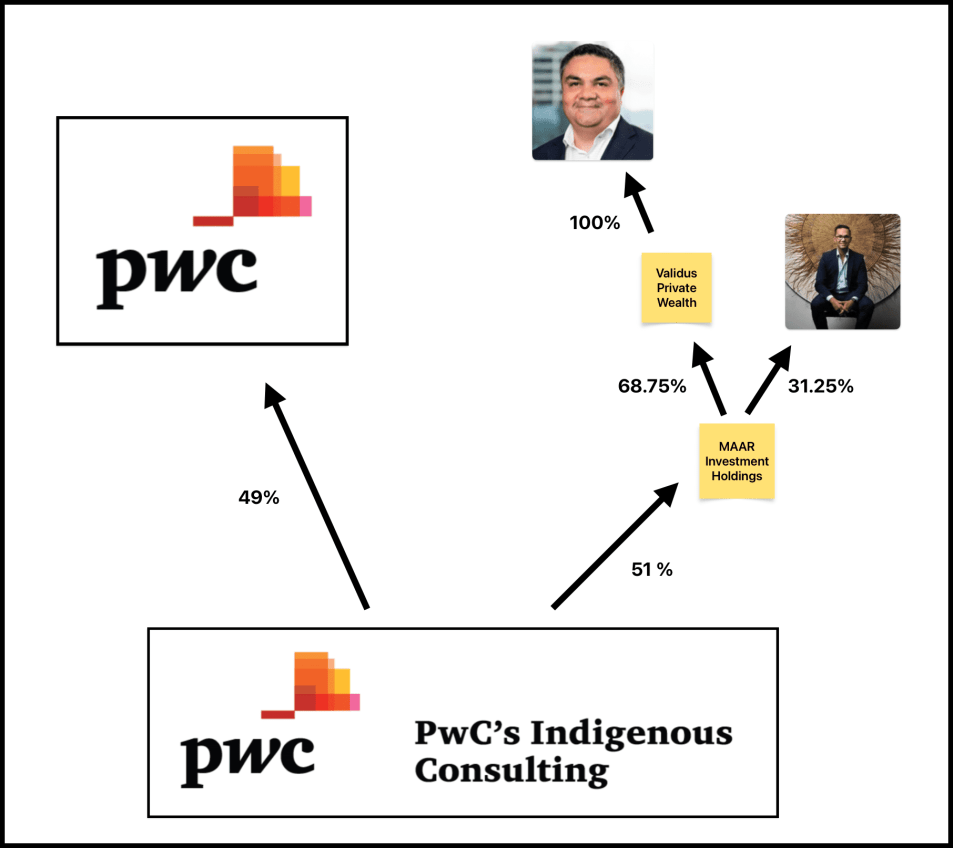

They include former Sydney financial adviser Gavin Brown, who owns 35% of PwC’s Indigenous Consulting through his private company Validus Private Wealth.

It can be further revealed that PwC’s Indigenous Consulting, which says it “works together with governments” to “close the gap”, has been given millions of dollars of contracts from the Northern Territory government, in addition to $44.67 million in federal contracts.

PwC and the National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA), which was created by the Morrison government in 2019 and has given PwC’s Indigenous Consulting more than $16 million, have each said PwC’s Indigenous Consulting is “separate” from PwC.

As previously revealed, that’s despite PwC owning 49% of PwC’s Indigenous Consulting, and the company’s address and “principal place of business” being at PwC’s Sydney headquarters.

Investigations show the other 51% is owned by just two people: Brown and former public servant Selwyn Button.

Searches of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) companies register show the 51% of the company not owned by PwC is owned by a private company called MAAR Investment Holdings, which is owned by Brown and Button.

Brown owns 68.75% of MAAR Investment Holdings and Button owns the other 31.25%.

Both Brown and Button are Indigenous.

That means PwC’s Indigenous Consulting is ultimately owned 49% by PwC (the biggest stake), 35% by Brown and 16% by Button. Brown holds his 68.75% in MAAR Investment Holdings through Validus Private Wealth, of which he owns 100%.

Brown’s LinkedIn profile states he “has spent his career in the wealth management and financial advice industries” being an “adviser to many clients, both individuals and companies”.

“He progressed to management of financial advice businesses and then managed ‘Private Clients’ (High Net Worth individuals etc) for an ASX-listed financial services group,” his LinkedIn bio states.

Button has held various public service positions.

Brown and Button are among the five directors of PwC’s Indigenous Consulting, and Brown is the company’s CEO. The other directors are PwC Australia partners David McKeering and Thomas Bowden, and businesswoman Donna Murray.

PwC’s Indigenous Consulting was founded in 2013 by PwC Australia’s then-CEO Luke Sayers, who was appointed CEO in 2012.

Fueling its success has been more than $14 million in “limited tender” contracts — including more than $10 million awarded under a procurement regime for small Indigenous businesses.

Brown, PwC and PwC’s Indigenous Consulting all refused to provide The Klaxon with a copy of its audited financial accounts, so what PwC’s Indigenous Consulting is currently worth is not known. Other key financial information, such as executive salaries, is also unknown.

In 2022 PwC’s Indigenous Consulting was given a record $13.78 million in federal grants.

Brown told The Klaxon: “We have never declared or paid a dividend.”

Whether or not dividends have been paid (whether profits have been drawn down) has no relation to what profits have been earned by the company. Rather, the profits simply remain in the company until they are drawn down.

“PwC’s Indigenous Consulting (PIC) is a separate organisation to PwC Australia — we are a supply nation certified business (i.e. greater than 50% ownership by Indigenous peoples),” said Brown.

“We have prioritised our people and purposes before profit, which has enabled us to grow from a start-up of just over a handful of people in October 2013, to a business which is now approximately 75 people, more than 50% of whom are themselves Indigenous peoples”.

As previously revealed, since 2015, PwC’s Indigenous Consulting has been given more than 100 contracts and “contract amendments” (almost all value amendments are upwards) from 19 federal government departments and agencies. Totalling $44.67 million, those are the contracts that are of sufficient size and type to require disclosure on the federal government’s tender registry AusTender.

The former Coalition government repeatedly froze public service hiring, while vastly increasing its spend on consultants and other contractors.

The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) has found that in the 2022 financial year, the Morrison government had engaged 53,900 contractors at a cost of $20.8 billion — or $385,185 each.

Among the dozens of “limited tender” deals given to PwC’s Indigenous Consulting is a Department of Social Services contract in February last year for exactly “$200,000.00” for “policy and program development services”.

Another Department of Social Services contract was “amended” nine times — with its cost increased each time.

It started at $1.22 million in March 2019 and by June 2021 it had increased almost four-fold to $4.34 million. Each “amendment” — which requires a new contract — is marked “Limited Tender … SME with at least 50% Indigenous ownership”.

PwC is one of the world’s largest businesses.

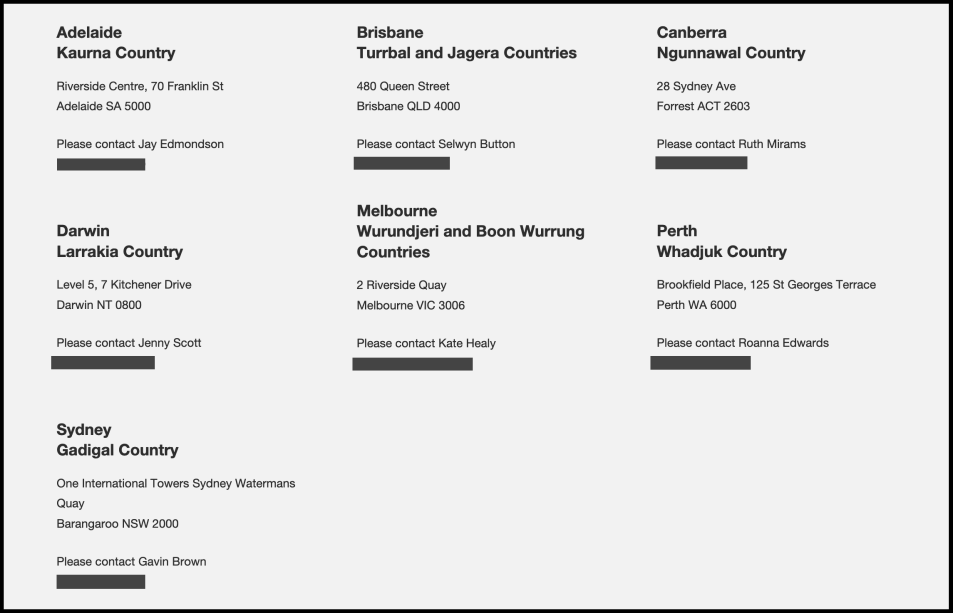

Searches of the Northern Territory tender registry show PwC’s Indigenous Consulting has also been given 17 contracts there since 2015.

Totalling $2.96 million, they include “$120,000.00” from the Department of the Chief Minister for a “Northern Territory Government Local Decision Making Framework”; $150,000 for “provision of specialist advice and support relating to child protection”; and $225,610 for “consultancy services for the development of the sports and recreation master plan”.

PwC’s Indigenous Consulting provides “advice to government” and “aims to be an emblem for Indigenous self-determination”, its website states.

PwC is embroiled in one of the biggest corporate scandals in Australian history, after being caught divulging confidential Australian government tax policy information to multinational PwC clients seeking to avoid Australian tax. In total, 14 companies accepted the advice, earning at least $2.5 million for the firm.

It gleaned the information while providing “advice” to government on creating new laws to prevent multinationals from avoiding Australian tax.

Facing extreme public pressure, the federal government on May 19 announced a clampdown on contracts, warning departments and agencies they “must” consider the “performance history” of potential suppliers, including failure to abide by “confidentiality provisions”.

It was reported as an “effective ban” on PwC.

Three days later, the NIAA gave PwC’s Indigenous Consulting a $745,292.57 contract for “strategic advice and review services”. Last week AusTender was updated to show the NIAA had given PwC’s Indigenous Consulting another contract — $91,982 for “stakeholder engagement and consultation services”.

The NIAA is by far the biggest federal funder of PwC’s Indigenous Consulting, giving it $16.3 million in contracts since 2019.

Over the past four years, almost two-thirds of contracts to PwC’s Indigenous Consulting by value have come from the NIAA — including a $10.2 million contract in April last year for “training and development services”.

PwC Australia spokesman Patrick Lane has said PwC’s Indigenous Consulting “is not part of PwC Australia” and “is its own entity”.

The NIAA said PwC’s Indigenous Consulting is “separate” from PwC Australia.

PwC’s Indigenous Consulting’s website — part of PwC Australia’s website — lists its offices across Australia’s states and territories.

In each case, that office is PwC’s head office in that state or territory.

This article first appeared at The Klaxon and is republished with permission.

Another foul stench that needs to be properly investigated. Hopefully the AFP are already down this rabbit hole in regards to their ongoing criminal investigation of PWC tax avoidance.

Another bunch of bureaucrats “tipping elbow”(watching their watch), whilst supposedly consulting.

AFP investigating Liberal party instigated fraud? Hahaha… oh wait, you’re being serious.

Seems Brown and Button have never heard of Chaim Rumkowski.

Button and Brown: the elite?

Parliament-was-Corporate … seems tax isn’t the only thing PwC like avoiding.

The other questions not being asked is: where does the money go and what does it pay for?