Stamp duty is a state tax on property transactions levied at a few percent of the value of the trade, with higher rates applying to higher-value trades.

One of the most popular tax reforms in Australia is to remove stamp duty and enact a broader land value tax, which is an annual tax levied on the assessed land value for each property, traded or not. It is usually applied at a rate of 1-2% of the land value.

Many miracles are meant to arise from this tax swap, from more household relocations to cheaper housing and greater economic efficiency.

But these claims are mostly based on hope, not evidence. I’ve debunked the main claims in these two articles.

The latest miracle claimed to arise from removing stamp duty is that it will increase home ownership.

A new paper in the Economic Record got some press coverage for its claims about how much removing stamp duty could increase home ownership. The economic and political tribes fell predictably into line behind it on social media.

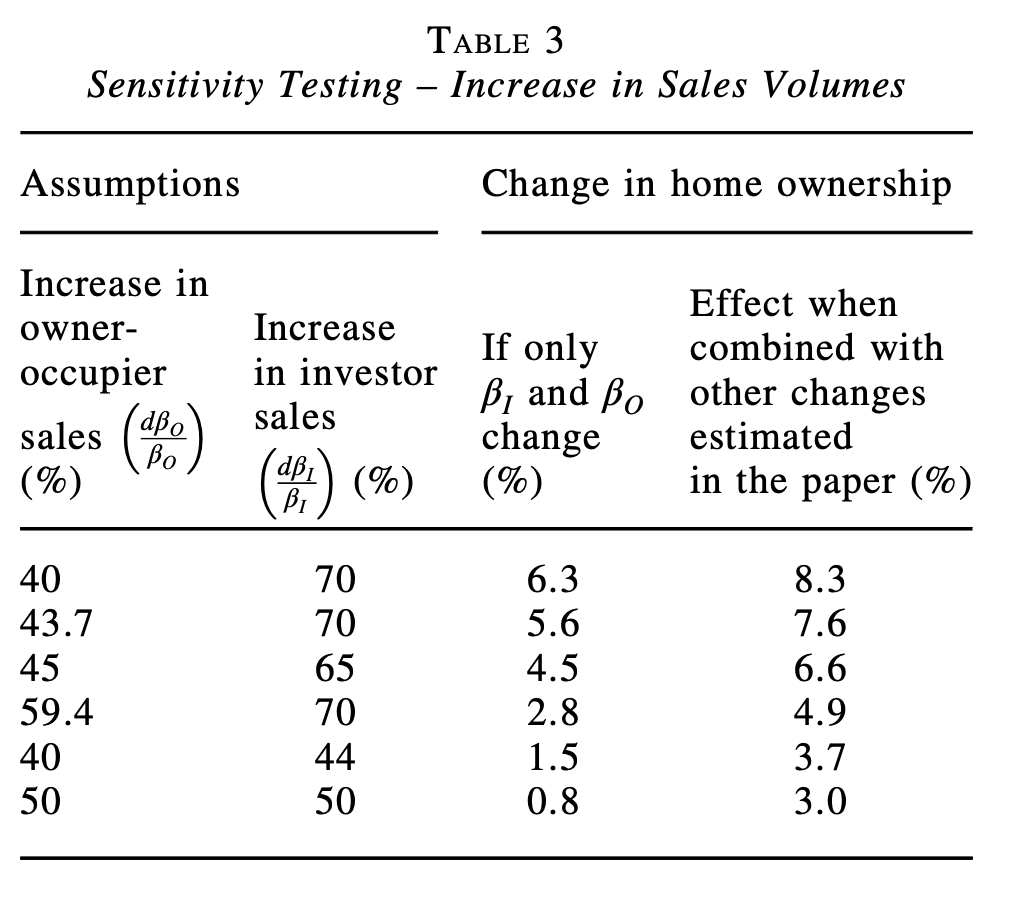

The main result of the paper was as follows:

The NSW government’s 2020 proposal to replace stamp duty on all properties with an annual tax based on unimproved land values is estimated to increase home ownership by 6.6%, through changes in purchaser holding periods, a shift of tax burden from investors to owner-occupiers and a relaxed deposit constraint.

In terms of home ownership rates:

Overall, the modelling suggests home ownership could increase in the long run from 67.1% of the private dwelling stock to 71.5%, which is a 6.6% increase.

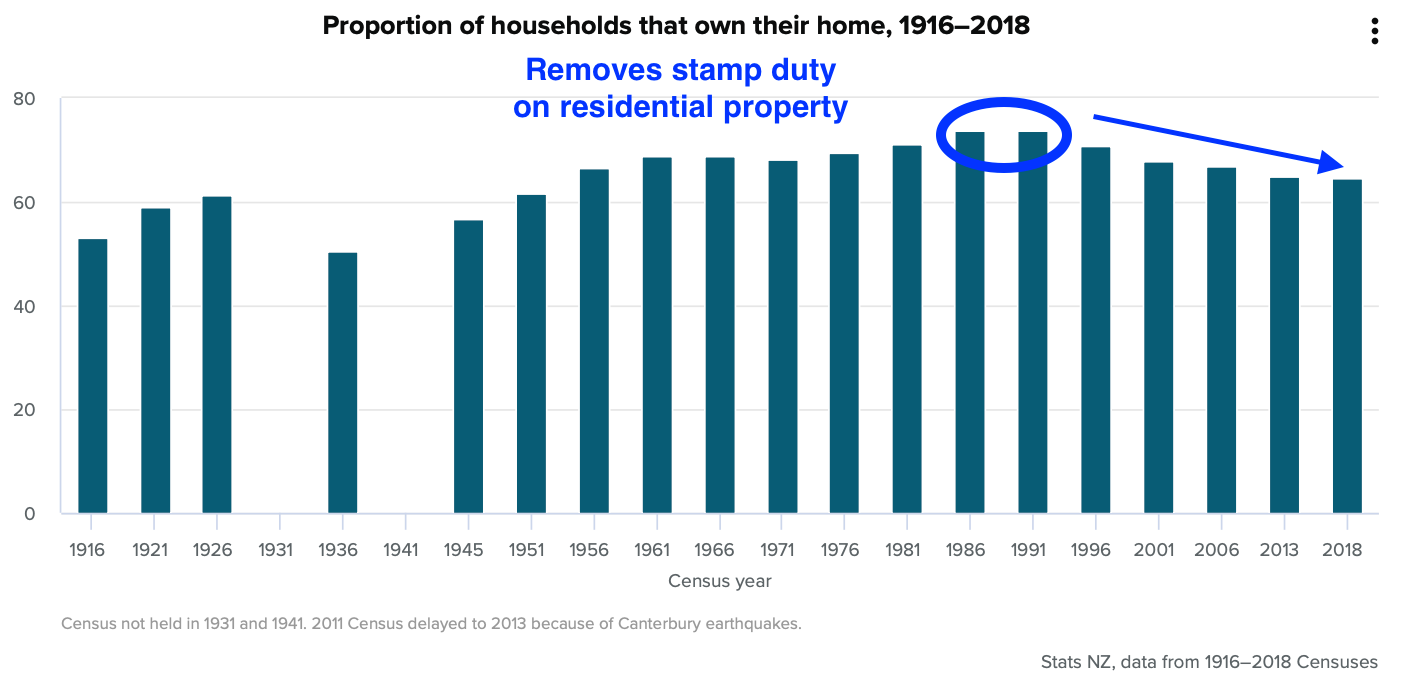

How is the New Zealand miracle going?

In 1988, New Zealand removed stamp duties from residential property trades, and in 1999 removed them from all property trades.

The outcome is that home ownership there is now the lowest it’s been in 70 years.

The chart below from Stats NZ shows a fall in the home ownership rate from 73.8% in 1991 to 64.5% today, which is a much bigger drop than Australia has seen in recent decades with its cumbersome stamp duties.

A miracle in the model

The new paper is based on a modelling exercise that assumes that increasing turnover will lead to a higher proportion of first-home buyers.

It’s not a bad paper. It shows the sensitivity of the results to various assumptions, the critical ones being how much extra turnover comes from investors or home owners selling (which are inputs to the model, not outputs).

But I think there are some strange assumptions.

For example, in a pure home ownership market with no investor buyers and no change in the stock of housing or number of households, changing the frequency of trades would not change the home ownership rate — it will always be 100%.

If stamp duty reduces the cost of trading, there will be more trading. But every seller is also a buyer, even at higher levels of turnover. If there are five sellers, that means there are exactly five buyers. If there are 10 sellers, there are exactly 10 buyers as well.

Changing the frequency of trade doesn’t change this fundamental relationship. Only if investors sell relatively more can higher turnover lead to higher home ownership. As we can see in the image above, this is exactly the assumption that generates the result of higher turnover leading to higher home ownership.

The forgotten forced renter moves

It is also weird to me that stamp duty is now often relabelled as a moving tax.

But stamp duty also taxes housing trades between investors, which usually force renter households to move when they don’t want to.

Stamp duty taxes turnover, which is not the same thing as mobility.

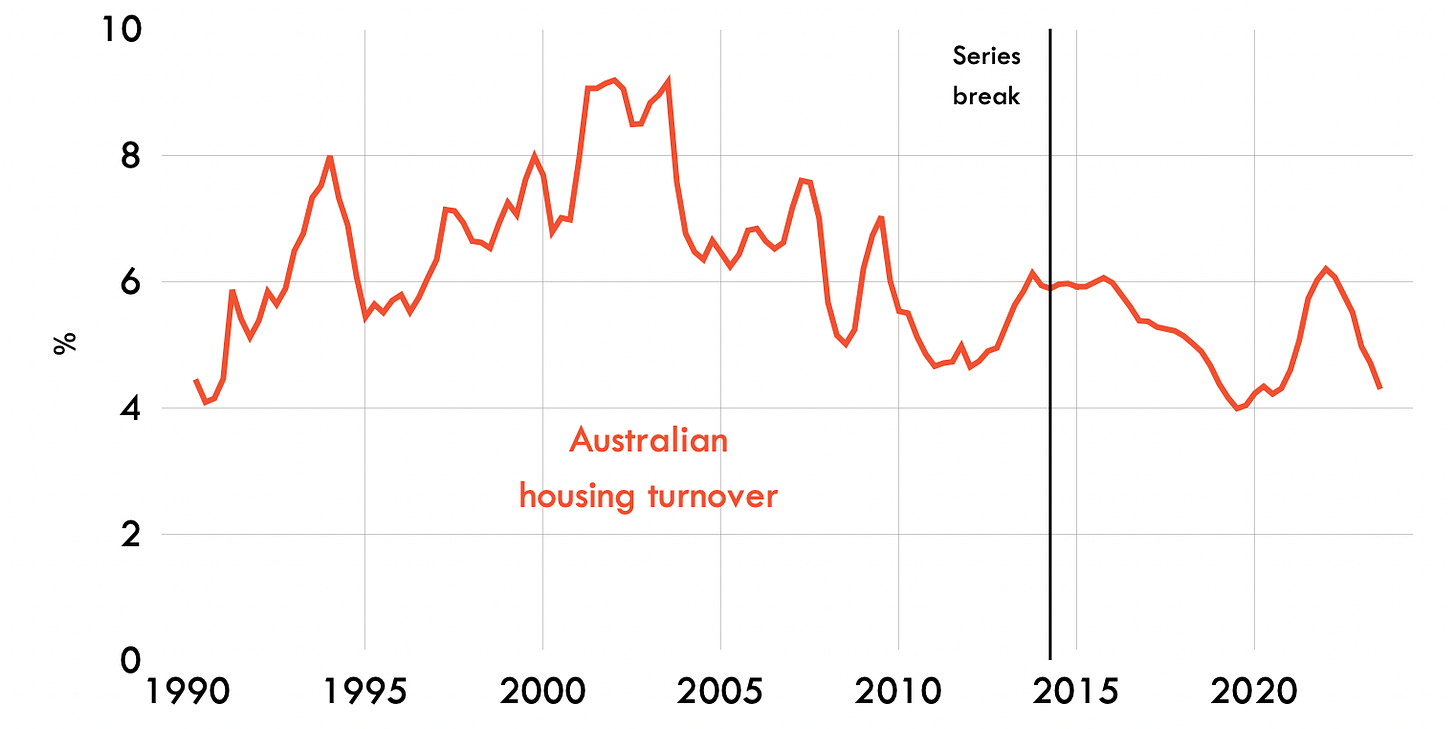

New Zealand has a housing turnover rate of about 7-9% per year, while Australia has a rate of about 4-6%. A sizable difference, most likely due to the low transaction costs there.

But that also means that renters in New Zealand are much more likely to be forced to move because of a home sale.

In Australia, surveys suggest that about 14% of renter moves are because a lease was not renewed for any reason. But in New Zealand, a survey of over 1,000 tenants in 2016 found that 30% of renter moves were because the landlords sold the house, with this being the reason behind 36% of renter moves in Auckland.

New Zealand Treasury has noted the gains to renters from fewer property transactions.

In Auckland, reducing the turnover of rental properties is likely desirable to increase tenants’ stability of tenure. As noted above, Auckland’s short-term housing market turnover is high, with houses with highest levels of short term turnover concentrated in areas with relatively large investor participation.

Reducing the cost of transacting by removing stamp duty is likely to have a much larger effect on the rate of transactions of landlords compared to home owners.

We know that people don’t buy expensive houses with the expectation of frequently selling and moving. Households choose to rent instead if they don’t plan to stay in one place. Sure, they do this partly because of stamp duty, but these behavioural responses also decrease the effect of stamp duty on reducing mobility.

In fact, 30% of renters in the Australian Bureau of Statistics housing mobility survey say that the costs associated with moving are why they wouldn’t move, but only 21% of owners say costs are a barrier to moving.

Less frequent trades improve stability

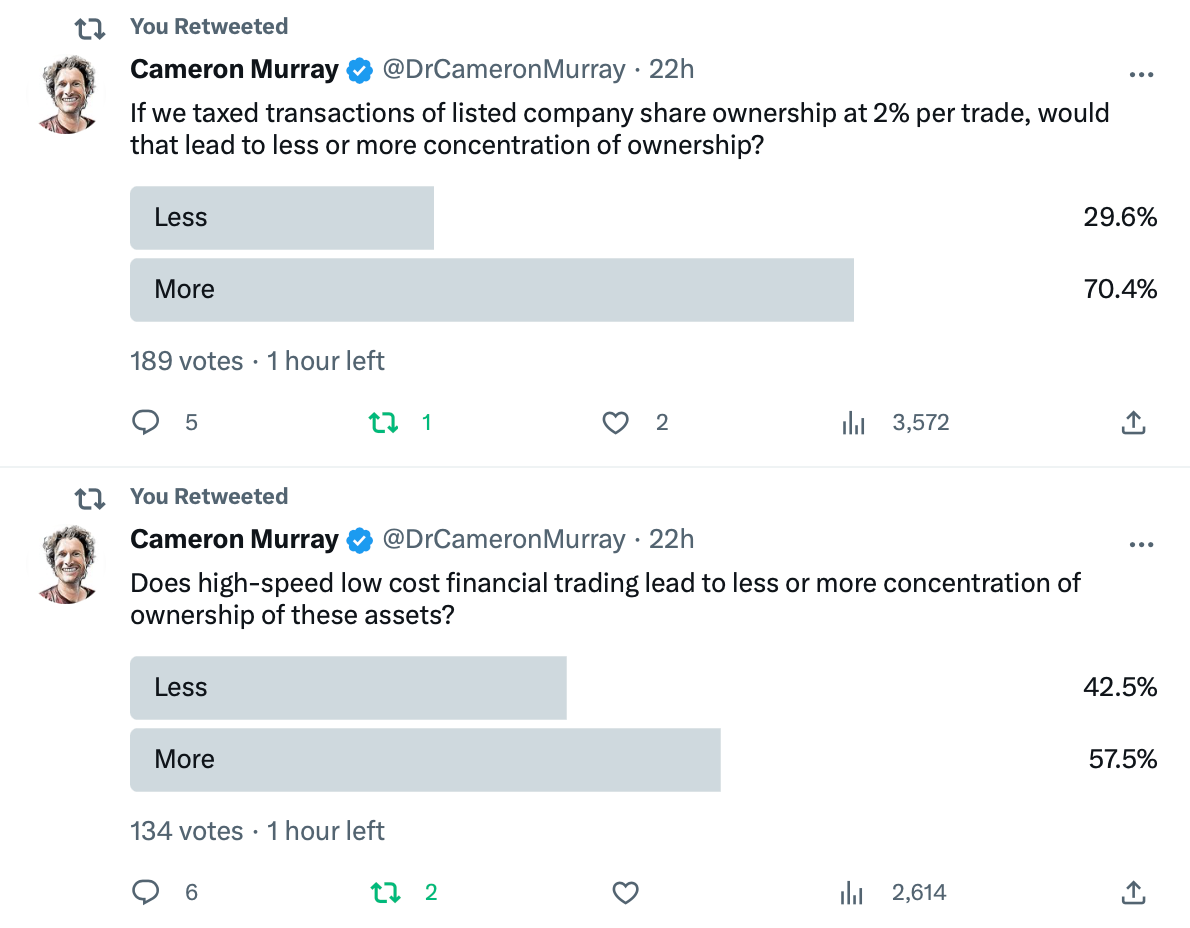

I ran two Twitter polls. One about whether adding costs to trading assets results in less or more concentrated ownership and one about removing costs.

Most people thought that both adding and removing costs to asset trading increased concentration of ownership.

Essentially, we all think any change is bad.

Let’s bring these threads together.

A new study reckons that removing stamp duty will increase home ownership by an astonishing 6%, reversing a half-century of decline. This seems a bold claim since the best real-life case study is New Zealand, and home ownership there declined after stamp duty was removed.

It turns out that the bold claim is based on the assumption that higher turnover means more investors selling and fewer homebuyers selling. The study assumed its result.

Indeed, lower turnover is generally good for renters. More investors selling means more forced and unnecessary renter moves, which is a big problem in New Zealand.

And when we ask people whether higher costs of trading means higher concentration of ownership (i.e. more investor owners owning more homes each, rather than broader home ownership) people have no idea.

This is republished with permission from Cameron Murray’s Fresh Economic Thinking Substack.

I can only relate this to my own circumstances. I have a largish house in what has become an expensive area. It was once full of various humans and puppies but not anymore. I would downsize but to do so in my area would barely cover the stamp duty. I am staying put.

“…in what has become an expensive area.” Australia, in other words?

If the removal of stamp duty decreases the cost, that should make buying a house more feasible for many. However, it would also make it more attractive for developers to build new homes to sell into the market. Surely that would increase home ownership in the long run.

The article had receipts to the contrary though.

That would possibly work if the duty-free price of the house did not increase to match the previous duty-inclusive price.

More money in the buyers’ pockets simply raises house prices. A one-off stamp duty is better than an annual tax. Council rates are bad enough already.

Don’t a lot of States already remove stamp duty now in lieu of a first home buyer’s grant? Removing for everyone will just make it even easier for those with too much to broaden their portfolio. How about a moratorium on foreign ownership for 5 years instead? Canada is trying this for two years. At least their government is actually trying something.

An investor has to price in the cost of land tax in their purchase price calculation

We shouldn’t be worried about who owns the home, clearly land tax is better than stamp as it puts the house in the hands of the people who value it most highly. Just like changes to NG and Cap gains, we shouldn’t worry about what it’ll do to prices (property is a zero sum game once you’re in) and simply in place the least bad taxes