Bushfire in the eastern Barkly region was downgraded over the weekend to an active blaze, but the 1.3-million-hectare fire scar provides a snapshot into the impact on landscapes with and without Indigenous fire management.

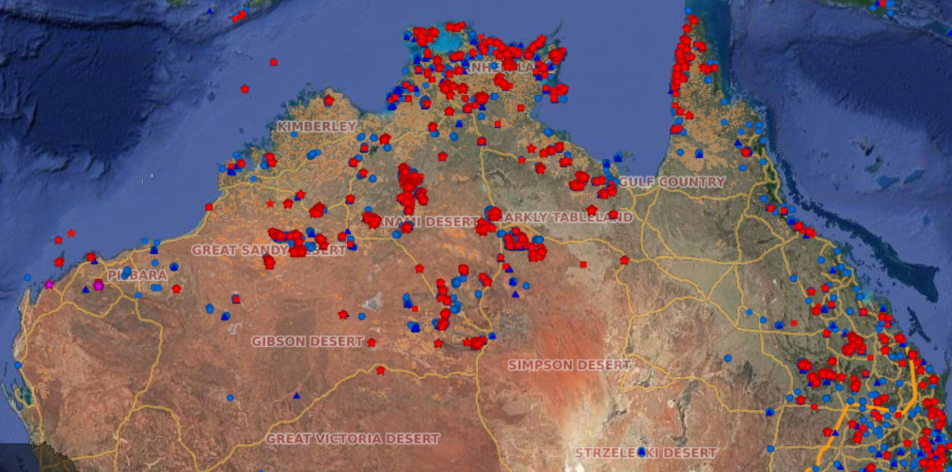

The Barkly blaze is one of many burning in the Northern Territory at the beginning of a fire season projected to be the territory’s worst since 2011. With predictions that as much as 80% of the territory is set to burn, it’s instructive to see the efficacy of Indigenous fire management.

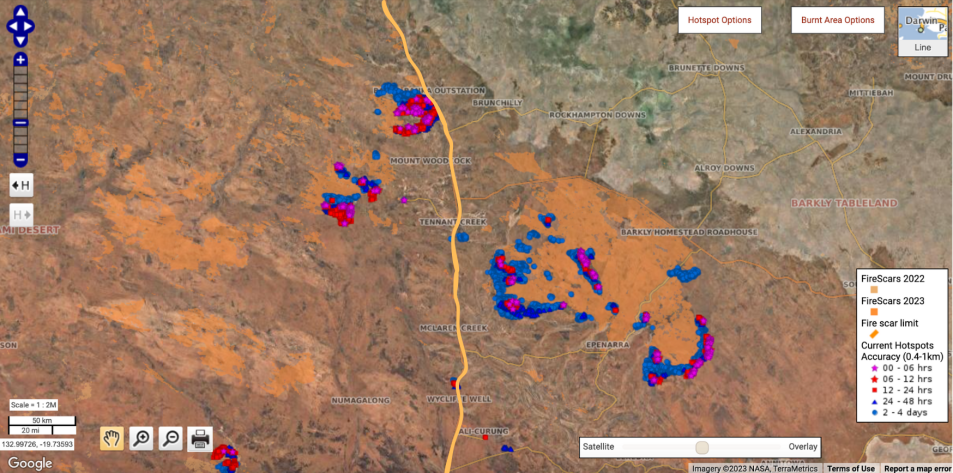

“Compare the eastern side of the highway to the west where fire hasn’t run rampant in the same way,” Indigenous Desert Alliance partnerships manager Gareth Catt told Crikey. “You can see in mapping on NAFI [North Australia Fire Information] a lot of burning done in April, March, May, June on the western Tanami side. That is what’s impeding the spread of some of those fires.”

He pointed to the patchwork “mosaic” burns on the west in comparison to the large blanket burn on the east of the highway and said that while it’s early in summer and fires in the Barkly could prove to be more widespread, the difference in the two was stark.

The alliance has long worked with Land Owners, Indigenous ranger groups and the Central Land Council to burn land throughout the Tanami year-round as part of management of country. Although these fires have a similar look and feel to typical hazard reduction burns, Catt said the main difference was that they didn’t aim to burn large parts of country in one hit: “Cultural burns are about putting a lot of small fires into country. We look at landscape more broadly — vegetation types which can be enhanced through fire and areas most likely to ignite where we can reduce the likelihood of them burning.”

These fires are conducted through ground and aerial operations, with burn locations determined by Traditional Owners.

In the east, Catt said they’ve had no footprint due to pastoral land owners not wanting to engage in (and not providing access to) burns on their properties: “We haven’t been able to work in a constructive way on that side of the highway.”

Central Land Council CEO Les Turner told Crikey that the absence of adequate land care on country with excess fuel loads was to blame for the scale and scope of the blaze: “The Barkly fires are burning in native vegetation that has been subject to near-record rainfall. This is a natural event except that the country is largely unmanaged in the way that it would have when it was occupied with its Indigenous traditional owners.”

Turner said consecutive years of excess rainfall promoted growth of native and non-native vegetation that’s since cured in hot and dry conditions ripe for burning en masse. Many species have infiltrated river corridors and creek lines that previously acted as natural fire breaks.

The NT Department of Environment, Parks and Water Security told Crikey feedback from weeds officers fighting the fires confirmed fuel loads in the Barkly were “all native vegetation”. They said buffel grass — the invasive and highly flammable weed burning in the Tjoritja/West MacDonnell Ranges fires — was not present in the Barkly region and had no impact on the blaze.

Crikey requested an interview with both weed officers and remote operations personnel. The department responded: “Maybe, once they’re done fighting the fires.”

Based on intel from remote land care practitioners and ops workers, Crikey understands fuel loads in the area were 99% native vegetation, although buffel was present in “small amounts” in water systems, along roads and on pastoral leases. The lack of comprehensive buffel mapping in the area and inability to access farms was said to have prevented proper assessment of the scale and scope of buffel growth. The dominant species were spinifex and an acacia shrub called turpentine which, although native, had “overrun the landscape due to many years of overgrazing”.

The native bush thrives in disturbed soils common to pastoral lands. In short: many hoofs churn up the dirt and where other native species die off, turpentine dominates. It’s highly flammable and smells like turpentine.

“On a warm day you can see oils evaporating from the top,” one worker said.

Rohan Fisher from the landscape knowledge visualisation lab at Charles Darwin University, and part of the team that manages mapping inputs and outputs for NAFI, said that Australia’s fire focus was far too “southern centric”, despite 95% of fire events occurring up north.

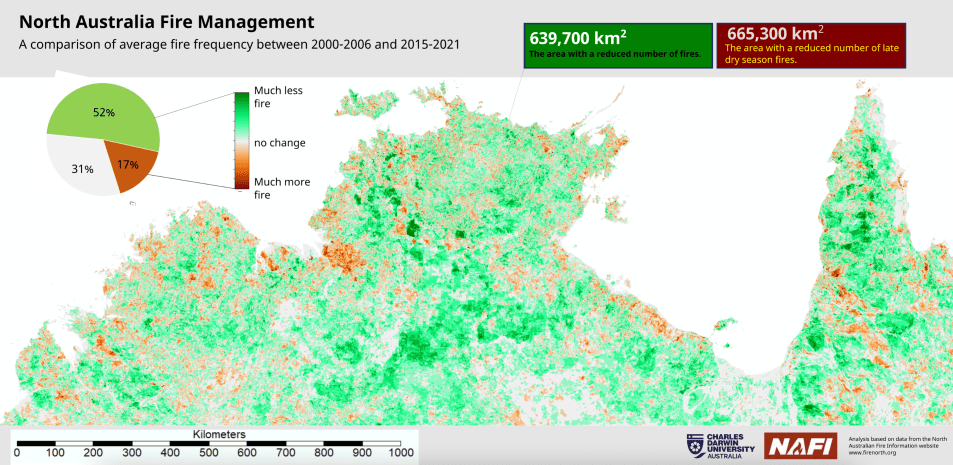

“If you talk to anyone in southern Australia, the only fires that ever occurred were in 2019-20,” he said, adding that northern Australia is home to “the most amazing ecological success story in Australia over the past 20 years” — the reduced frequency of fires in an area of around 600,000 square kilometres due to Indigenous burning regimes.

“Indigenous people are doing some of the best fire management in the world. But the pyro-ecological literacy of Australia and Australians is just atrocious.”

2m-hectare blanket burn? Is that 2 millihectares?

Surely you meant 2M hectare, “M” being the abbreviation for “mega”, meaning a million

Oh for some science literacy amongst our journalistic class!

Pretty sure he meant 2m-hectares, “m” being a very commonly used abbreviation for “million”, meaning million.

Sadly m is used for million in finance. PaulM is correct, M is the right prefix here. A small m means one thousandth.

Maybe if you’re writing SI units (a hectare is not), and if the form was “ml”, “mm”, “mg”, etc.

But nobody would write “2m-grams” if they meant two milligrams, any more than they would “2M-joules” to mean two megajoules.

General Pedantic up there would have looked no less silly, but arguably more correct, asking what a metre-hectare was and whether two of them was a lot or a little.

Oh dear you are quite right!

Mea culpa; when I was seven, some friends and myself started a bushfire in Tennant Creek while playing with matches. You have no idea how fast this sh*t gets out of control in the dry season. It was truly scary, and I never played with matches again. That was before global warming and buffel grass. Australia is looking at not just one catastrophe in the next eight months, but several. Tennant only just avoided disaster last week.

For the record, I got the belt for my actions, and it was nasty. The early Sixties were not a PC decade.

My memory is fading and I may be corrected but the growth after 73/4 floods resulted in a fire traveled 1100ks from west to east. It was an amazing site as the flames subsided going downhill and flared going up hill. Amazing and scary to watch. We are slow learners.

Maybe kids these days are less likely to get a whack but also less likely to be given the freedom to do such a thing in the first place. In the suburbs any way. An interesting trade off. I wonder what had the bigger impact on you, the belt or the truly scary experience. From the way you’ve written it, the latter.

At the societal level, scary bush-fires don’t seem to teach us effectively, and the planet has not administered a big enough belt … yet.

Interesting. Based on the information in the article, it seems possible that some of the additional fire impact on the east side is due to the more flammable vegetation (turpentine) that is growing due to overgrazing. But I am sure the NAFI analysis of the effectiveness of controlled burns takes the vegetation into account.

And so long as the Referendum fails, none of us down south will never never know.

Put a match to a turpentine bush on a hot day and it goes up like it had been soaked in kerosene. The intensity of the burn from a large area of turpentine would be terrible.